When heat turns into electricity at 1000 °C.

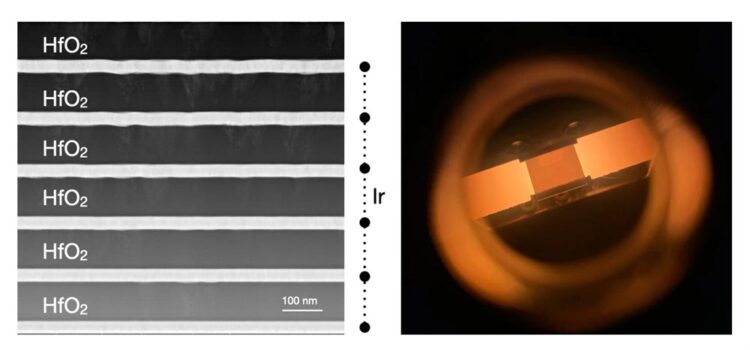

The image on the left shows a cross-sectional transmission electron microscope image of the emitter with distinct iridium and hafnium oxide layers. The image on the right shows the selective emitter at 1000 °C in an in-situ x-ray diffraction annealing chamber.

(c) Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon

Thermophotovoltaics: Researchers develop new resistant emitter based on iridium.

Together with the Technical University of Hamburg and Aalborg University, researchers from the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon have developed a new selective emitter based on iridium for thermophotovoltaics. Iridium was thus used for the first time as a material for an emitter, and in the experiments, it showed particular endurance at high temperatures around 1000 °C. Their study results were published today in the journal Advanced Materials and open up new perspectives for producing electricity from heat.

The conversion of heat into electricity is the principle of thermophotovoltaics. To make the heat efficiently usable in the form of radiant energy, so-called selective emitters are needed. They sit between the heat source and the photovoltaic cell and emit only a certain part of the radiation while suppressing the other. The challenge here is that the conversion of heat into electricity takes place at high temperatures around 1000°C – the emitter must therefore be able to withstand these temperatures without losing the accuracy of its selectivity. In cooperation with the Technical University of Hamburg (TUHH) and Aalborg University, researchers at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon have now succeeded in producing a new emitter based on the resistant metal iridium that can withstand these conditions without losing its effectiveness.

“With iridium, we address both aspects at the same time: selectivity and temperature stability,” says Alexander Petrov, who works on optical properties of materials at TUHH. “Selective emitters based on iridium are very good at suppressing unwanted radiation and do not react with oxygen. Iridium is a precious metal like gold, but suitable for high-temperature applications.”

“By avoiding the adverse effects of oxidation, we have unlocked the potential for more efficient and sustainable systems.” reports Gnanavel Vaidhyanathan Krishnamurthy, lead author of the study and a scientist at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon. “This innovation opens the doors to new possibilities in waste heat recovery, solar thermal power generation and beyond.”

The emitter’s function

In thermophotovoltaics, as in photovoltaics, radiant energy is converted into electricity by a photovoltaic cell. However, in thermophotovoltaics the radiant energy does not come from the sun, but from a heat source, such as is used in the steel industry. The emitter is located between the heat source and the solar cell. It consists of several very thin layers (metal and oxide alternately), which should remain unchanged at high temperatures to enable heat to be converted into electricity. For this purpose, it ideally emits only short-wave photons and suppresses long-wave ones – it thus has a selective effect. This is important because the photovoltaic cell is not able to convert the long-wave radiation into electricity. At high temperatures, however, most metals oxidise and the function of the emitter fails. As the researchers were able to show, the newly developed selective emitter made of iridium and hafnium oxide retains its function completely over 100 hours at 1000 °C – the metal withstands the demanding challenges without any losses, as the researchers were able to show through X-ray examinations. The successful development of selective emitters based on iridium is an important step towards the further development of thermophotovoltaics.

In the transition to renewable energy, securing a constant power supply is of great importance. Thermophotovoltaics could not only generate electricity from industrial waste heat, but also make an important contribution to the conversion of the energy supply to renewable energies. Here, the energy generated by photovoltaics and wind turbines, which naturally fluctuates over time, is temporarily stored in heat reservoirs in order to extract it again later – when the sun is not shining or the wind is not blowing – and convert it into electrical energy, which is then continuously available, by means of thermophotovoltaics, and in this way stabilise the energy grids.

The research work is part of the Collaborative Research Centre 986 of the TUHH and the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon, which deals with customised multiscale material systems.

Wissenschaftliche Ansprechpartner:

Dr Michael Störmer I Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon | Institute of functional materials for sustainability | T: +49 (0) 4152 87-2628 I michael.stoermer@hereon.de I www.hereon.de

Originalpublikation:

Krishnamurthy, G. V., Chirumamilla, M., Krekeler, T., Ritter, M., Raudsepp, R., Schieda, M., Klassen, T., Pedersen, K., Petrov, A. Yu., Eich, M., Störmer, M., Iridium Based Selective Emitters for Thermophotovoltaic Applications. Adv. Mater. 2023, 2305922. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202305922

https://www.hereon.de/innovation_transfer/communication_media/news/111849/index.php.en

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Power and Electrical Engineering

This topic covers issues related to energy generation, conversion, transportation and consumption and how the industry is addressing the challenge of energy efficiency in general.

innovations-report provides in-depth and informative reports and articles on subjects ranging from wind energy, fuel cell technology, solar energy, geothermal energy, petroleum, gas, nuclear engineering, alternative energy and energy efficiency to fusion, hydrogen and superconductor technologies.

Newest articles

Faster, more energy-efficient way to manufacture an industrially important chemical

Zirconium combined with silicon nitride enhances the conversion of propane — present in natural gas — needed to create in-demand plastic, polypropylene. Polypropylene is a common type of plastic found…

Energy planning in Ghana as a role model for the world

Improving the resilience of energy systems in the Global South. What criteria should we use to better plan for resilient energy systems? How do socio-economic, technical and climate change related…

Artificial blood vessels could improve heart bypass outcomes

Artificial blood vessels could improve heart bypass outcomes. 3D-printed blood vessels, which closely mimic the properties of human veins, could transform the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Strong, flexible, gel-like tubes…