Research reveals a cellular basis for a male biological clock

Researchers at the University of Washington have discovered a cellular basis for what many have long suspected: Men, as well as women, have a reproductive clock that ticks down with age.

A recent study revealed that sperm in men older than 35 showed more DNA damage than that of men in the younger age group. In addition, the older men’s bodies appeared less efficient at eliminating the damaged cells, which could pass along problems to offspring.

“When you talk about having children, there has been a lot of focus on maternal age,” said Narendra Singh, research assistant professor in the UW Department of Bioengineering and lead researcher on the study. “I think our study shows that paternal age is also relevant.”

Charles Muller, with the UW Department of Urology and a collaborator on the study, recently presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine in Seattle.

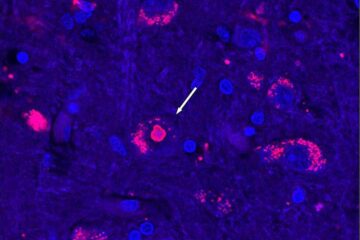

In the study, researchers recruited 60 men, age 22 to 60, from laboratory and clinical groups. A computerized semen analysis was performed for each of the subjects, looking for breaks in sperm cell DNA and evidence of apoptosis, or cell suicide. Normally, when something goes irreparably wrong in a cell, that cell is programmed to kill itself as a means of protecting the body.

The researchers found that men over age 35 had sperm with lower motility and more highly damaged DNA in the form of DNA double-strand breaks. The older group also had fewer apoptotic cells – an important discovery, Singh said.

“A really key factor that differentiates sperm from other cells in the body is that they do not repair their DNA damage,” he said. “Most other cells do.”

As a result, the only way to avoid passing sperm DNA damage to a child is for the damaged cells to undergo apoptosis, a process that the study indicates declines with age.

“So in older men, the sperm are accumulating more damage, and those severely damaged sperm are not being eliminated,” Singh said. “That means some of that damage could be transmitted to the baby.” More research is needed to determine just what the risks are. Other reseachers in the study included Richard E. Berger, UW professor of urology. The work was supported by the Paul G. Allen Foundation for Medical Research.

For more information, contact Singh at 206- 685-2060 or narendra@u.washington.edu, or

Muller at 206-543-9504 or cmuller@u.washington.edu

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.washington.edu/All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Recovering phosphorus from sewage sludge ash

Chemical and heat treatment of sewage sludge can recover phosphorus in a process that could help address the problem of diminishing supplies of phosphorus ores. Valuable supplies of phosphorus could…

Efficient, sustainable and cost-effective hybrid energy storage system for modern power grids

EU project HyFlow: Over three years of research, the consortium of the EU project HyFlow has successfully developed a highly efficient, sustainable, and cost-effective hybrid energy storage system (HESS) that…

After 25 years, researchers uncover genetic cause of rare neurological disease

Some families call it a trial of faith. Others just call it a curse. The progressive neurological disease known as spinocerebellar ataxia 4 (SCA4) is a rare condition, but its…