Melting glaciers have big carbon impact

Scientists have done field work in Tibet and Alaska, among other places as part of this study. Credit: Robert Spencer/Florida State

More specifically, what happens to all of the organic carbon found in those glaciers when they melt?

That's the focus of a new paper by a research team that includes Florida State University assistant professor Robert Spencer. The study, published in Nature Geoscience, is the first global estimate by scientists at what happens when major ice sheets break down.

“This is the first attempt to figure out how much organic carbon is in glaciers and how much will be released when they melt,” Spencer said. “It could change the whole food web. We do not know how different ecological systems will react to a new influx of carbon.”

Glaciers and ice sheets contain about 70 percent of the Earth's freshwater and ongoing melting is a major contributor to sea level rise. But, glaciers also store organic carbon derived from both primary production on the glaciers and deposition of materials such as soot or other fossil fuel combustion byproducts.

Spencer, along with colleagues from Alaska and Switzerland, studied measurements from ice sheets in mountain glaciers globally, the Greenland ice sheet and the Antarctic ice sheet to measure the total amount of organic carbon stored in the global ice reservoir.

It's a lot.

Specifically, as glaciers melt, the amount of organic carbon exported in glacier outflow will increase 50 percent over the next 35 years. To put that in context, that's about the amount of organic carbon in half of the Mississippi River being added each year to the ocean from melting glaciers.

“This research makes it clear that glaciers represent a substantial reservoir of organic carbon,” said Eran Hood, the lead author on the paper and a scientist with the University of Alaska Southeast. “As a result, the loss of glacier mass worldwide, along with the corresponding release of carbon, will affect high-latitude marine ecosystems, particularly those surrounding the major ice sheets that now receive fairly limited land-to-ocean fluxes of organic carbon.”

Spencer said he and his colleagues are continuing on this line of research and will do additional studies to try to determine exactly what the impact will be when that carbon is released into existing bodies of water.

“The thing people have to think about is what this means for the Earth,” Spencer said. “We know we're losing glaciers, but what does that mean for marine life, fisheries, things downstream that we care about? There's a whole host of issues besides the water issue.”

Other institutions collaborating on the paper are University of Alaska Southeast, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne and the Alaska Science Center.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Studies and Analyses

innovations-report maintains a wealth of in-depth studies and analyses from a variety of subject areas including business and finance, medicine and pharmacology, ecology and the environment, energy, communications and media, transportation, work, family and leisure.

Newest articles

A universal framework for spatial biology

SpatialData is a freely accessible tool to unify and integrate data from different omics technologies accounting for spatial information, which can provide holistic insights into health and disease. Biological processes…

How complex biological processes arise

A $20 million grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) will support the establishment and operation of the National Synthesis Center for Emergence in the Molecular and Cellular Sciences (NCEMS) at…

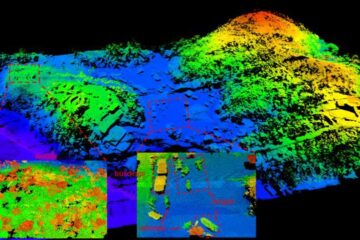

Airborne single-photon lidar system achieves high-resolution 3D imaging

Compact, low-power system opens doors for photon-efficient drone and satellite-based environmental monitoring and mapping. Researchers have developed a compact and lightweight single-photon airborne lidar system that can acquire high-resolution 3D…