Using nanodiamonds as sensors just got easier

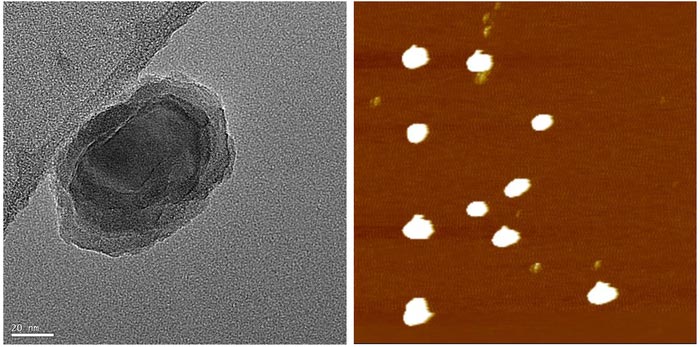

Left: A transmission electron microscope image shows a single nanodiamond with a 70-nanometer diamond core on a carbon grid. Rochester researchers have developed a new way to use defects in diamonds called nitrogen vacancy centers to measure the temperature of the samples they are attached to with outstanding spatial and temporal resolution. Right: An atomic force microscope (AFM) image shows nanodiamonds arranged in an “R” (for Rochester) pattern using AFM nanomanipulation.

Credit: Pickel Lab/University of Rochester

University of Rochester researchers adapt excited state lifetime thermometry to extract temperatures of nanoscale materials from light emitted by nitrogen vacancy centers.

For centuries people have placed the highest value on diamonds that are not only large but flawless.

Scientists, however, have discovered exciting new applications for diamonds that are not only incredibly small but have a unique defect.

In a recent paper in Applied Physics Letters, researchers at the University of Rochester describe a new way to measure temperature with these defects, called nitrogen vacancy centers, using the light they emit. The technique, adapted for single nanodiamonds by Andrea Pickel, assistant professor of mechanical engineering, and Dinesh Bommidi, a PhD student in her lab, allowed them to precisely measure, for the first time, the duration of these light emissions, or “excited state lifetimes,” at a broad range of temperatures.

The discovery earned the paper recognition as an American Institute of Physics “Scilight,” a showcase of what AIP considers the most interesting research across the physical sciences.

The Rochester method gives researchers a less complicated, more accurate tool for using nitrogen vacancy centers to measure the temperature of nanoscale-sized materials. The approach is also safe for imaging sensitive nanoscale materials or biological tissues and could have applications in quantum information processing.

For example, Pickel says, the technique could help define and measure the precise optimal temperatures needed to switch the resistivity of materials in nanoscale-sized phase change memory devices as part of the ongoing quest to store ever larger amounts of data in ever smaller devices.

“These excited state lifetime measurements are really helpful for measuring temperature changes that take place not only over small length scales, but also on fast time scales,” Pickel says. “It turns out these lifetimes are quite fast—only about 25 to 30 nanoseconds at room temperature, and even faster at higher temperatures.”

New technique offers multiple advantages over standard approach

Nitrogen vacancy centers are often created by bombarding commercial diamonds with ions, then milling them down into the nanoscale diamond particles used by researchers. In a nitrogen vacancy center, one of the carbon atoms is replaced with a nitrogen atom, and the adjoining nitrogen atom is missing. “It turns out, these nitrogen vacancy centers are fluorescent, so if you send light in—from a laser, for example—you can also get light out of them,” Pickel says.

To date, most research groups have used a technique called optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR) to measure temperature using nitrogen vacancy centers. However, the method has several drawbacks, Pickel says. OMDR requires placing a microwave antenna near the sample to do the measurements. That can be a complicated setup. The antenna can also cause heating that could harm sensitive materials or biological samples. Moreover, the microwave signal can be lost altogether at higher temperatures.

Instead, Pickel and Bommidi adapted an existing technique called excited state lifetime thermometry and applied it to nitrogen vacancy centers in single nanodiamonds for the first time.

The nanodiamonds, scattered on the surface of a material to be tested, are located using atomic force microscopy. The researchers developed a way to use the microscope probe tip to then move individual nanodiamonds to desired locations.

“If you know there’s a really critical location where you want to measure the temperature on a device or sample, this gives us a way to move the nanodiamond sensor to exactly that spot—almost like using a putter in a little nanodiamond golf game,” Pickel says.

The researchers then excite the nitrogen vacancy centers with green laser pulses. This sends electrons into a higher energy state. When the laser shuts off and the electrons return to a normal state, photons are emitted. The duration of this emission is a precise indicator of temperature.

Because the nanodiamonds are the same temperature as the material they are placed on, the readings are accurate for the material as well, Pickel says.

“We are excited about this because it is all optical; we don’t need to have a microwave antenna,” Pickel says. “And even when we increase the temperature, we retain access to our measurement signal, so we can make temperature measurements at pretty fast time scales. That’s important at the nanoscale, because when you have really small samples, they can change temperatures really fast.”

Journal: Applied Physics Letters

DOI: 10.1063/5.0072357

Method of Research: Experimental study

Subject of Research: Not applicable

Article Title: Temperature-dependent excited state lifetimes of nitrogen vacancy centers in individual nanodiamonds

Article Publication Date: 21-Dec-2021

Media Contact

Robert Marcotte

University of Rochester

bmarcotte@ur.rochester.edu

Office: 585-329-3583

All latest news from the category: Power and Electrical Engineering

This topic covers issues related to energy generation, conversion, transportation and consumption and how the industry is addressing the challenge of energy efficiency in general.

innovations-report provides in-depth and informative reports and articles on subjects ranging from wind energy, fuel cell technology, solar energy, geothermal energy, petroleum, gas, nuclear engineering, alternative energy and energy efficiency to fusion, hydrogen and superconductor technologies.

Newest articles

Sea slugs inspire highly stretchable biomedical sensor

USC Viterbi School of Engineering researcher Hangbo Zhao presents findings on highly stretchable and customizable microneedles for application in fields including neuroscience, tissue engineering, and wearable bioelectronics. The revolution in…

Twisting and binding matter waves with photons in a cavity

Precisely measuring the energy states of individual atoms has been a historical challenge for physicists due to atomic recoil. When an atom interacts with a photon, the atom “recoils” in…

Nanotubes, nanoparticles, and antibodies detect tiny amounts of fentanyl

New sensor is six orders of magnitude more sensitive than the next best thing. A research team at Pitt led by Alexander Star, a chemistry professor in the Kenneth P. Dietrich…