Bubbles go high-tech to fight tumors

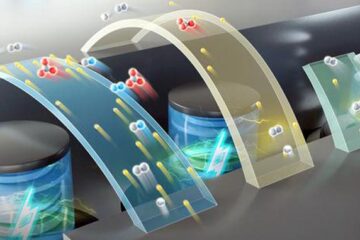

The process of blocking blood flow to a tumor is called embolization, and using gas bubbles is a new technique in embolotherapy. What makes it so promising is that the technique allows doctors to control exactly where the bubbles are formed, so blockage of blood flow to surrounding tissue is minimal, said Joseph Bull, assistant professor of biomedical engineering at U-M.

The research of Bull and collaborator Brian Fowlkes, an associate professor in the Department of Radiology in the U-M Medical School, is currently focused on the fundamental vaporization and transport topics that must first be understood in order to translate this developmental technique to the clinic.

In traditional embolotherapy techniques, the so-called cork that doctors use to block the blood flow—called an emboli—is solid. For instance, it could be a blood clot or a gel of some kind. A major difficulty with these approaches is restricting the emboli to the tumor to minimize destruction of surrounding tissue, without extremely invasive procedures, Bull said. The emboli must be delivered by a catheter placed into the body at the tumor site.

Gas bubbles, on the other hand, allow very precise delivery because their formation can be controlled and directed from the outside, by a focused high intensity ultrasound.

This envisioned technique is actually a two-step process, Bull said. First, a stream of encapsulated superheated perfluorocarbon liquid droplets goes into the body by way of an intravenous injection. The droplets are small enough that they don’t lodge in vessels. Doctors image the droplets with standard ultrasound, and once the droplets reach their destination, scientists hit them with high intensity ultrasound. The ultrasound acts like a pin popping a water balloon. After the shell pops, the perfluorocarbon expands into a gas bubble that is approximately 125 times larger in volume than the droplet.

“If a bubble remained spherical its diameter would be much larger than that of the vessel,” Bull said. “So it deforms into a long sausage-shaped bubble that lodges in the vessel like a cork. Two or three doses of bubbles will occlude most of the (blood) flow.” Without blood flow, the tumor dies.

Because the bubble is so big, it’s critical to get the right vessel in order not to damage it.

“How flexible the vessel is plays a very important role in where you do this,” Bull said. That is the subject of a paper coming out on gas embolotherapy in the August issue of the Journal of Biomechanical Engineering.

Bull’s post doctoral student Tao Ye was a co-author on the paper.

The technique could be very valuable in treating certain cancers, such as renal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma, the most common form of liver cancer, causing about 1,250,000 deaths annually. However, cirrhosis of the liver makes it difficult to treat by the conventional method of removing the tumor and surrounding tissue, because so much of the liver is already damaged. This cancer has a high mortality rate.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.umich.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

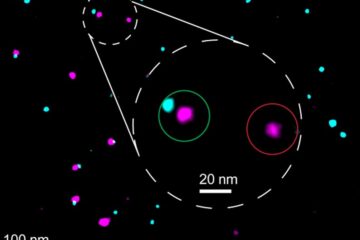

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…