Cretaceous octopus with ink and suckers — the world's least likely fossils?

Everyone knows what an octopus is. Even if you have never encountered one in the flesh, the eight arms, suckers, and sack-like body are almost as familiar a body-plan as the four legs, tail and head of cats and dogs.

Unlike our vertebrate cousins, however, octopuses don't have a well-developed skeleton, and while this famously allows them to squeeze into spaces that a more robust animal could not, it does create problems for scientists interested in evolutionary history. When did octopuses acquire their characteristic body-plan, for example? Nobody really knows, because fossil octopuses are rarer than, well, pretty much any very rare thing you care to mention.

The body of an octopus is composed almost entirely of muscle and skin, and when an octopus dies, it quickly decays and liquefies into a slimy blob. After just a few days there will be nothing left at all. And that assumes that the fresh carcass is not consumed almost immediately by hungry scavengers. The result is that preservation of an octopus as a fossil is about as unlikely as finding a fossil sneeze, and none of the 200-300 species of octopus known today has ever been found in fossilized form. Until now, that is.

Palaeontologists have just identified three new species of fossil octopus discovered in Cretaceous rocks in Lebanon. The five specimens, described in the latest issue of the journal Palaeontology, are 95 million years old but, astonishingly, preserve the octopuses' eight arms with traces of muscles and those characteristic rows of suckers. Even traces of the ink and internal gills are present in some specimens. 'These are sensational fossils, extraordinarily well preserved' says Dirk Fuchs of the Freie University Berlin, lead author of the report. But what surprised the scientists most was how similar the specimens are to modern octopus: 'these things are 95 million years old, yet one of the fossils is almost indistinguishable from living species.” This provides important evolutionary information.

“The more primitive relatives of octopuses had fleshy fins along their bodies. The new fossils are so well preserved that they show, like living octopus, that they didn't have these structures.' This pushes back the origins of modern octopus by tens of millions of years, and while this is scientifically significant, perhaps the most remarkable thing about these fossils is that they exist at all.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

A universal framework for spatial biology

SpatialData is a freely accessible tool to unify and integrate data from different omics technologies accounting for spatial information, which can provide holistic insights into health and disease. Biological processes…

How complex biological processes arise

A $20 million grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) will support the establishment and operation of the National Synthesis Center for Emergence in the Molecular and Cellular Sciences (NCEMS) at…

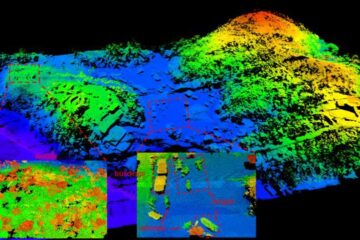

Airborne single-photon lidar system achieves high-resolution 3D imaging

Compact, low-power system opens doors for photon-efficient drone and satellite-based environmental monitoring and mapping. Researchers have developed a compact and lightweight single-photon airborne lidar system that can acquire high-resolution 3D…