UCSD researchers determine fibrin depletion decreases multiple sclerosis symptoms

Tissue damage due to Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is reduced and lifespan lengthened in mouse models of the disease when a naturally occurring fibrous protein called fibrin is depleted from the body, according to researchers at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) School of Medicine.

The study, reported online the week of April 19, 2004 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, identifies fibrin as a potential target for therapeutic intervention in the disease, which affects an estimated one million people worldwide.

However, the research team cautions that fibrin plays an important role in blood clotting and systemic fibrin depletion could have adverse effects in a chronic disease such as MS. Therefore, additional research is needed to specifically target fibrin in the nervous system, without affecting its ability as a blood clotting protein.

“Multiple sclerosis is a nervous system disease with vascular damage, resulting from the leakage of blood proteins, including fibrin, into the brain,” said the study’s first author, Katerina Akassoglous, Ph.D., a UCSD School of Medicine assistant professor of pharmacology. “Our study shows that fibrin facilitates the initiation of the inflammatory response in the nervous system and contributes to nerve tissue damage in an animal model of the disease.”

MS is an autoimmune disease that affects the central nervous system (CNS), causing a variety of symptoms including loss of balance and muscle coordination, changes in cognitive function, slurred speech, bladder and bowel dysfunction, pain, and diminished vision. While the exact cause of MS is unknown, a hallmark of the disease is the loss of a material called myelin that coats nerve fibers, and the inability of the body’s natural processes to repair the damage.

Although fibrin is best known for its important role in blood clotting, recent studies have shown that fibrin accumulates in the damaged nerves of MS patients, followed by a break down of myelin. However, the cellular mechanisms of fibrin action in the central nervous system have not been known, nor have scientists determined if fibrin depletion could alleviate or lessen the symptoms of MS.

In work performed at The Rockefeller University, New York and the UCSD School of Medicine, in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Vienna, Austria and Hellenic Pasteur Institute, Greece, researchers studied normal mice and transgenic mice with an MS-like condition. The normal mice had normal spinal cords and with no fibrin deposits in the central nervous system. In contrast, the transgenic mice showed fibrin accumulation, inflammation and a degradation of the myelin in their spinal cord. When transgenic mice were bred without fibrin, they developed a later onset of the MS-like paralysis as compared to their transgenic brothers that had fibrin. In addition, the fibrin-depleted mice lived for one additional week longer than the normal, disease-impacted mice. This difference is significant in animal models such as mice that have very short lifespans.

Fibrin’s role in excessive inflammation was shown in a follow-up experiment where transgenic mice were shown to experience high expression of pro-inflammatory molecules, followed by myelin loss, as compared to the fibrin-negative transgenic mice with no signs of inflammation or myelin destruction.

In addition to the genetic deletion of fibrin, the researchers tested drug-induced fibrin depletion, which was accomplished by administering ancrod, a snake venom protein, to the transgenic mice. Consistent with the genetics-based experiments, the pharmacological depletion also delayed the onset of inflammatory myelin destruction and down-regulated the immune response. Previous studies by other investigators who used ancrod in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), another animal model of MS, also showed amelioration of neurologic symptoms.

In the current study, the investigators also used cell culture studies to determine that fibrin activates macrophages, the major cell type that contributes to inflammatory myelin destruction.

Akassoglou said that “further research to identify the cellular and molecular mechanisms that fibrin utilizes in the nervous system will provide pharmacologic targets that will specifically block the actions of fibrin in nervous system disease.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Wadsworth Foundation Award, and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

Sidney Strickland, Ph.D., Laboratory of Neurobiology and Genetics, The Rockefeller University, New York, in whose lab Akassoglou first began her studies, was the senior author of the paper. Additional authors were Ryan Adams, Ph.D., UCSD Department of Pharmacology; Jan Bauer, Ph.D. and Hans Lassmann, M.D., Laboratory of Experimental Neuropathology, University of Vienna, Austria; Lesley Probert, Ph.D., and Vivi Tseveleki, B.Sc., Laboratory of Molecular Genetics, Hellenic Pasteur Institute, Athens, Greece; and Peter Mercado, B.Sc., The Rockefeller University

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.ucsd.edu/All latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

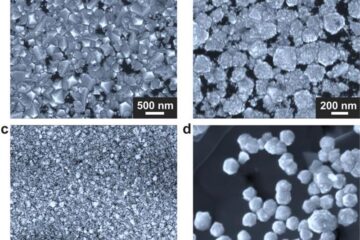

Making diamonds at ambient pressure

Scientists develop novel liquid metal alloy system to synthesize diamond under moderate conditions. Did you know that 99% of synthetic diamonds are currently produced using high-pressure and high-temperature (HPHT) methods?[2]…

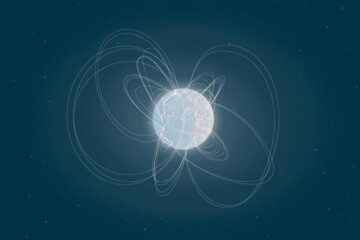

Eruption of mega-magnetic star lights up nearby galaxy

Thanks to ESA satellites, an international team including UNIGE researchers has detected a giant eruption coming from a magnetar, an extremely magnetic neutron star. While ESA’s satellite INTEGRAL was observing…

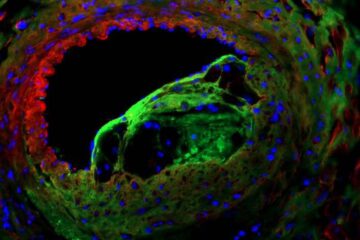

Solving the riddle of the sphingolipids in coronary artery disease

Weill Cornell Medicine investigators have uncovered a way to unleash in blood vessels the protective effects of a type of fat-related molecule known as a sphingolipid, suggesting a promising new…