Pesticide resistance warning after gene discovery

Scientists have raised concerns following the discovery of a single gene that gives vinegar flies resistance to a wide range of pesticides, including the banned DDT.

Scientists are worried as this single mutation unexpectedly provides the fly (Drosophila melanogaster) with resistance to a range of commonly available, but chemically unrelated, pesticides. Significant also, is this species is rarely targeted with pesticides and many of the chemicals it is resistant to, it has never been exposed to before.

Researchers at the University of Melbourne and the Centre for Environmental Stress and Adaptation Research (CESAR) that made the discovery believe the mutation arose in Drosophila soon after the introduction of DDT and has since spread throughout the world. The gene has also persisted rather than, as expected, disappearing as the use of DDT around the world declined.

“This is a warning that we may need to rethink our overall strategies to control insect pests,” says University of Melbourne geneticist, Dr Phil Batterham, and Program Leader for the Chemical Stress Program within CESAR, a special research centre that includes researchers from the Universities of Melbourne, La Trobe and Monash.

“The fact that a single mutation can confer resistance to DDT and a range of unrelated pesticides, even to those the species has never encountered, reveals new risks and costs to the chemical control of pest insects. Unless we reassess our current methods of pest management, our future options for control may become severely restricted,” he says.

“If this mutation was found on a pest insect, many options for the chemical control of that insect would have been removed.”

The research is published in the latest edition of the prestigious journal Science.

Batterham suggests that it is now imperative that research and industry focus on refining integrated pest management, which incorporates a broad arsenal of pest control measures including biological control and crop management techniques.

The Drosophila resistance gene, named Cyp6g1, is part of a large family of genes called the Cytochrome P450 genes that are found in many species, including humans.

Previous studies have implicated some members of this P450 family in pesticide resistance. However the function of the majority of the 90 Drosophila P450 genes is unknown.

CESAR is now analysing these genes to determine their function in Drosophila and in the pest insects, the cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) and the sheep blowfly responsible for flystrike (Lucilia cuprina).

“Our capacity to control pests would be significantly improved if we understood the defence mechanisms controlled by these genes,” says Batterham.

In the Drosophila, Cyp6g1 confers resistance by producing up to 100 times more than the normal level of protein that breaks down DDT and other pesticides. Given the number of P450 genes present in Drosophila, it was unexpected that a single version of one gene could be associated with such widespread resistance, and that this resistance also applied to a wide range of compounds that bear no resemblance to each other in structure or mode of function. These compounds include organochlorines, organophosphorous, carbamate and insect growth regulator insecticides.

“Our research, so far, does not unequivocally demonstrate that Cyp6g1 is the sole culprit for this resistance, but the current evidence leaves little doubt that about its central role,” says Batterham.

Species will normally lose mutations that protected it against a particular pesticide once that pesticide ceases to be used. This is because, in the absence of the pesticide, the mutation suddenly confers a disadvantage. In this case, the Drosophila has maintained the resistance gene and is still ’fit’. That is, the mutation does not confer any disadvantage, so it persists in the population.

“This highlights more than ever that what we do today to control pests could irreversibly change the gene pool of that species,” says Batterham.

“Researchers investigating pesticide resistance sometimes fails to take sufficient notice of research into Drosophila. It maybe a model genetic organism, but it is still an insect and things that happen to Drosophila happen to other insects,” he warns.

“This research showed how easy it is for a single mutation to have such a diverse impact. A similar mutation in a pest species could have devastating consequences” he says.

The primary research was done by Dr. Phil Daborn (a former PhD student under Dr Batterham and Professor John McKenzie at the University of Melbourne) in the laboratory of Professor Richard ffrench-Constant at the University of Bath and current University of Melbourne students, Michael Bogwitz and Trent Perry, supervised by Dr. Batterham and Dr. David Heckel. Other collaborators include Professor Tom Wilson at Colorado State University and Dr. Rene Feyereisen at INRA (Centre de Recherches d’Antibes, France).

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.unimelb.edu.au/All latest news from the category: Agricultural and Forestry Science

Newest articles

A universal framework for spatial biology

SpatialData is a freely accessible tool to unify and integrate data from different omics technologies accounting for spatial information, which can provide holistic insights into health and disease. Biological processes…

How complex biological processes arise

A $20 million grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) will support the establishment and operation of the National Synthesis Center for Emergence in the Molecular and Cellular Sciences (NCEMS) at…

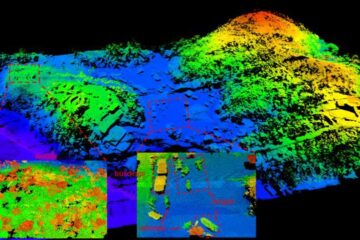

Airborne single-photon lidar system achieves high-resolution 3D imaging

Compact, low-power system opens doors for photon-efficient drone and satellite-based environmental monitoring and mapping. Researchers have developed a compact and lightweight single-photon airborne lidar system that can acquire high-resolution 3D…