Under pressure — Extreme atmosphere stripping may limit exoplanets' habitability

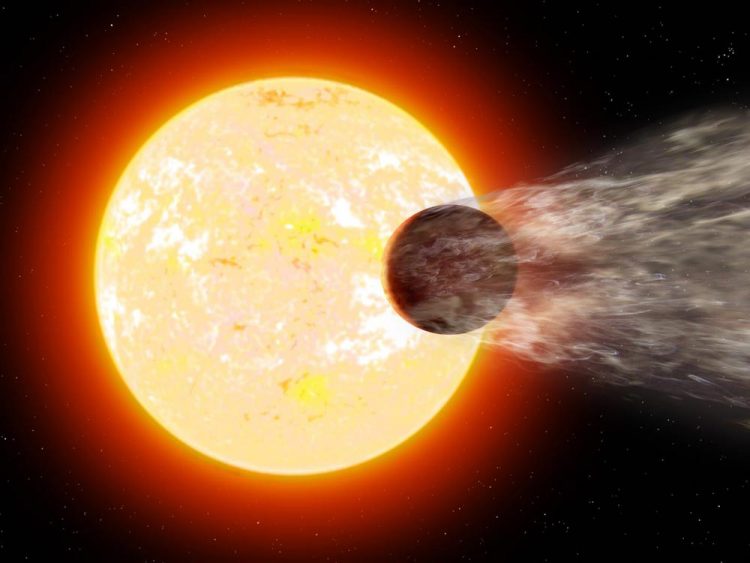

This is an artist's impression of HD189733b, showing the planet's atmosphere being stripped by the radiation from its parent star. Credit: Ron Miller

Coronal mass ejections (CMEs) are huge explosions of plasma and magnetic field that routinely erupt from the Sun and other stars. They are a fundamental factor in so called “space weather”, and are already known to potentially disrupt satellites and other electronic equipment on Earth.

However, scientists have shown that the effects of space weather may also have a significant impact on the potential habitability of planets around cool, low mass stars – a popular target in the search for Earth-like exoplanets.

Traditionally an exoplanet is considered “habitable” if its orbit corresponds to a temperature where liquid water can exist. Low mass stars are cooler, and therefore should have habitable zones much closer in to the star than in our own solar system, but their CMEs should be much stronger due to their enhanced magnetic fields.

When a CME impacts a planet, it compresses the planet's magnetosphere, a protective magnetic bubble shielding the planet. Extreme CMEs can exert enough pressure to shrink a magnetosphere so much that it exposes a planet's atmosphere, which can then be swept away from the planet. This could in turn leave the planetary surface and any potential developing lifeforms exposed to harmful X-rays from the nearby host star.

The team built on recent work done at Boston University, taking information about CMEs in our own solar system and applying it to a cool star system.

“We figured that the CMEs would be more powerful and more frequent than solar CMEs, but what was unexpected was where the CMEs ended up” said Christina Kay, who led the research during her PhD work.

The team modelled the trajectory of theoretical CMEs from the cool star V374 Pegasi and found that the strong magnetic fields of the star push most CMEs down to the Astrophysical Current Sheet (ACS), the surface corresponding to the minimum magnetic field strength at each distance, where they remain trapped.

“While these cool stars may be the most abundant, and seem to offer the best prospects for finding life elsewhere, we find that they can be a lot more dangerous to live around due to their CMEs” said Marc Kornbleuth, a graduate student involved in the project.

The results suggest that an exoplanet would need a magnetic field ten to several thousand times that of Earth's to shield their atmosphere from the cool star's CMEs. As many as five impacts a day could occur for planets near the ACS, but the rate decreases to one every other day for planets with an inclined orbit.

Merav Opher, who advised the work, commented, “This work is pioneering in the sense that we are just now starting to explore space weather effects on exoplanets, which will have to be taken into account when discussing the habitability of planets near very active stars.”

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

Sea slugs inspire highly stretchable biomedical sensor

USC Viterbi School of Engineering researcher Hangbo Zhao presents findings on highly stretchable and customizable microneedles for application in fields including neuroscience, tissue engineering, and wearable bioelectronics. The revolution in…

Twisting and binding matter waves with photons in a cavity

Precisely measuring the energy states of individual atoms has been a historical challenge for physicists due to atomic recoil. When an atom interacts with a photon, the atom “recoils” in…

Nanotubes, nanoparticles, and antibodies detect tiny amounts of fentanyl

New sensor is six orders of magnitude more sensitive than the next best thing. A research team at Pitt led by Alexander Star, a chemistry professor in the Kenneth P. Dietrich…