Drop in found out

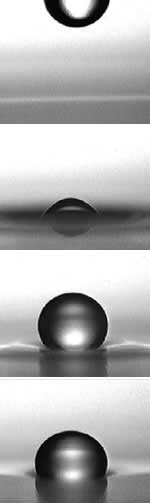

Long drop: soap and air keep water afloat on water. <br>© Y. Amarouchene

Air lets water droplets skim across the kitchen sink.

Scientists have found the answer to a question pondered over many a kitchen sink: why do little droplets skim across the surface of washing-up water rather than mix with it?

Yacine Amarouchene and colleagues at the University of Bordeaux in Talence, France have discovered that the height from which the drops fall has no effect on their lifespan1.

Soap, detergent – and indeed food grease – are ’surfactants’. They form a kind of skin on the surface of water that stabilizes a droplet, preventing it from merging where it rests. Droplets of pure water coalesce in a few thousandths of a second; when they contain a little surfactant they last hundreds of times longer.

The interest in coalescing droplets goes beyond the kitchen sink. When applying thin coats of a liquid as a spray, for example in car-painting, droplets need to merge quickly and smoothly at the surface of the wet film. Emulsions and foams, meanwhile, are sustained by inhibiting or slowing the coalescence of droplets or bubbles. Amarouchene’s group hope their theory might help chemical engineers and technologists to promote or prevent the effect, as required.

Droplets containing soap or detergent that fall a short distance onto a water surface bounce as if on a trampoline, the researchers found. The droplets then rest in a slight dip with a very thin film of air separating the two water surfaces.

How long the droplet lasts depends on how quickly the air is squeezed out from this interface, which in turn depends on the concentration of surfactants at the droplet surface. For pure water, the air film can thin very fast. A skin of surfactants at the water surface makes it harder for air to flow past. Air flow deforms this skin; and deformed skin slows the flow further.

The researchers find that, for a droplet of a particular size and containing a particular amount of surfactant, there is a characteristic residence time on the surface. Dropping them from increasing heights simply increases the chance of rupture on impact – it doesn’t alter the average lifetime of the drops that survive.

References

- Amarouchene, Y., Cristobal, G. & Kellay, H. Noncoalescing drops. Physical Review Letters, 87, 206104 (2001).

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Sea slugs inspire highly stretchable biomedical sensor

USC Viterbi School of Engineering researcher Hangbo Zhao presents findings on highly stretchable and customizable microneedles for application in fields including neuroscience, tissue engineering, and wearable bioelectronics. The revolution in…

Twisting and binding matter waves with photons in a cavity

Precisely measuring the energy states of individual atoms has been a historical challenge for physicists due to atomic recoil. When an atom interacts with a photon, the atom “recoils” in…

Nanotubes, nanoparticles, and antibodies detect tiny amounts of fentanyl

New sensor is six orders of magnitude more sensitive than the next best thing. A research team at Pitt led by Alexander Star, a chemistry professor in the Kenneth P. Dietrich…