Novel model of childhood obesity

The consumption of sweetened soft drinks by children has more than doubled between 1965 and 1996 and the contribution of these drinks to the development of childhood obesity is a cause for concern. Few studies have attempted to investigate the interactions between diet and the body’s energy balance control systems in early life, for obvious reasons. A model of childhood obesity using fast-growing juvenile rats has been developed by scientists at Aberdeen’s Rowett Research Institute and it is beginning to reveal new insights into how the brain responds to overeating.

The need for a better understanding of what is happening to the body’s energy balance control mechanisms during the development of obesity is becoming increasingly important as we struggle, and often fail, to treat weight gain with weight-loss diets. There are many studies of diet-induced obesity with adult rats but very few with juvenile rats. The Aberdeen scientists successfully developed a potential model for childhood obesity using fast-growing juvenile rats that were fed different combinations of high-energy diets in combination with a high-energy liquid drink.

The ability of liquid diets to stimulate overeating in rats more readily than solid diets is well documented, but the mechanism of this effect, and specifically the interaction of these obesity-inducing diets with the body’s energy balance control systems has not been explored in any depth.

The recently-published studies showed large changes in the brain’s signalling systems when the young rats were overeating, but the response was the same whether the rats were eating solid food, or receiving a high-energy drink. Although the high-energy diets eaten by the rats produced this response, it failed to make the young rats reduce the amount of food they were eating.

“The brain’s response to over-eating which we showed in this study is actually part of the same system that is designed to stop animals starving to death. When an animal is hungry, or food is in short supply, the brain signals are very effective at making it try and find food at all costs. There’s a clear evolutionary benefit in having this system,” said Professor Julian Mercer who led the study at the Rowett Institute.

“However, when the system is effectively put into reverse, when animals are overeating, we can clearly see a response, but for some reason this time it doesn’t make the rats change their behaviour, and so they continue to overeat. Perhaps the evolutionary drive to stop overeating isn’t as powerful as the drive not to starve. It seems likely that these obesity-inducing diets also engage the parts of our brain which are to do with pleasure and reward, and our future work with this model will investigate these systems.

“It’s also interesting to note that the response we measured was to the weight gain by the rats and it was the same whether the source of the extra energy was solid food or the high-energy drink,” said Professor Mercer.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.rowett.ac.ukAll latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

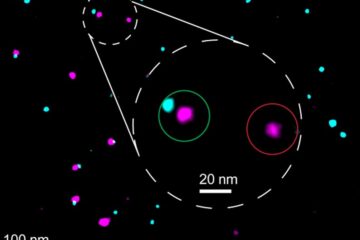

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…