Vaccine hope for malaria

Malaria infects around 400 million people every year and kills between one and three million, mostly children.

Dr Richard Pleass, from the Institute of Genetics, said: “Our results are very, very significant. We have made the best possible animal model you can get in the absence of working on humans or higher primates, as well as developing a novel therapeutic entity.”

Using blood from a group of people with natural immunity to the disease, a team from the School of Biology refined and strengthened the antibodies using a new animal testing system which, for the first time, mimics in mice the way malaria infects humans. When injected into mice, these antibodies protected them against the disease.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) says malaria is a public health problem in more than 90 countries and describes it as by far the world's most important tropical parasitic disease. It kills more people than any other communicable disease except tuberculosis and more than 90 per cent of all malaria cases are in sub-Saharan Africa. According to WHO, the dream of the global eradication of malaria is beginning to fade with the growing number of cases, rapid spread of drug resistance in people and increasing insecticide resistance in mosquitoes.

Until now there has been no reliable animal model for human malaria. Mice do not get sick when infected with the blood-borne parasite that causes malaria in people. And the immune system of mice shows a different response to humans when it comes into contact with the parasite.

This meant that despite making a promising antibody vaccine that worked against the parasite in a lab dish, the team could not test it in a living animal.

In a new study published in the journal PLoS Pathogens an open access journal published by the Public Library of Science — Dr Pleass and his collaborators in London, Australia and The Netherlands describe how they got around the problem by creating a mouse model of the human malaria infection. They took a closely related mouse parasite and genetically modified it to produce an antigen that the human immune system recognises.

Next, they genetically altered the mouse’s immune system to produce a “human molecule” on its white blood cells that recognises the parasite and, together with antibodies, destroys it. In trials the team showed that human antibodies given to the mice protected them from the parasite.

The team, who were funded by the Medical Research Council and the European Union, are now hoping to refine the model with a view to starting the first phase of clinical trials in humans.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.nottingham.ac.ukAll latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

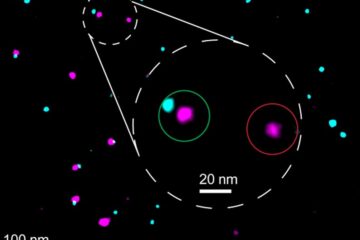

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…