Fire without smoke: Tracking down the most primitive black holes in the universe

The Spitzer Space Telescope against an infrared sky (computer-generated image). With Spitzer\'s help, astronomers have now found the most primitive black holes in the universe. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech <br>

Located at a distance of 12,7 billion light-years from Earth, we see these black holes or, more precisely, the bright galactic nuclei powered by these black holes, as they were 12,7 billion years ago, less than a billion years after the big bang. The existence of such primitive black holes had long been surmised, but until now, none had been observed. The results will be published in the March 18, 2010 issue of the journal Nature.

Quasars are the core regions of galaxies which contain active black holes. Such black holes are surrounded by brightly glowing “accretion disks”: disk of swirling matter that is spiraling towards the black hole. Such disks are among the brightest objects in the universe; in consequence, quasars are so bright that even at great distances, it is possible to investigate their physical properties in some detail.

It takes about 13 billion years for light from the most distant known quasars to reach us. In other words: We see these quasars as they were about 13 billion years ago, less than a billion years after the Big Bang. Looking that far into the past, one might expect to see half-formed, rather primitive precursors of more recent quasars. But in 2003, when the first of these very distant quasars were observed, researchers were greatly surprised to find that they were not markedly different in appearance from their modern kin.

Now a team of astronomers led by Linhua Jiang (University of Arizona, Tucson), which includes researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg and the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, has, for the first time, observed what appear to be very early, primitive quasars: quasars in an early stage of evolution, which are markedly different from quasars in the modern universe.

The astronomers used NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope to observe infrared light from those extremely distant quasars. With infrared observations, one can identify the signature of hot dust, which is a standard feature of modern quasars – in such quasars, the central glowing disk (which is comparable in size to our whole Solar System) is surrounded by a gigantic dust torus (which is about a thousand times larger). In two of the 20 quasars observed, the dust signature proved to be conspicuously absent. This suggested that these two quasars might be very primitive: The very early universe contained no dust at all, so the first stars and galaxies should have been dust-free. They should be intensely hot and radiate brightly, but contain no dust particles: fire without smoke. The existence of such low-dust or even dust-free quasars had long been surmised, but such objects had not been observed – until now.

Thoroughly examining all available data, the astronomers found that none of the quasars that are closer to Earth – so that we see them at a later stage of their evolution – come even close to being this dust-free. Also, they found that, for the very distant quasars, there is a strong correlation between the mass of the quasar's central black hole and the amount of dust present. This indicates an evolutionary process, in which the central black hole grows rapidly by swallowing up surrounding matter, while, at the same time, more and more hot dust is produced over time.

All available evidence points towards the conclusion that finally, astronomers have managed to see quasar evolution in action, and that the two dust-free quasars indeed represent the most primitive black hole systems we know: quasars at an early stage of their evolution, too young to have formed a detectable amount of dust around them.

Contact

Dr. Fabian Walter (Coauthor)

Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany

Phone: (0|+49) 6221 – 528 225

E-mail: walter@mpia.de

Background information

The results described here will be published as Jiang et al. “Dust-Free Quasars in the Early Universe” in the March 18, 2010 issue of Nature.

The team members are Linhua Jiang and Xiaohui Fan (University of Arizona, Tucson), W. N. Brandt (Pennsylvania State University), Chris L. Carilli (National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Socorro, New Mexico), Eiichi Egamii (University of Arizona, Tucson), Dean C. Hines (Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colorado), Jaron D. Kurk (Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, formerly Max Planck Institute for Astronomy), Gordon T. Richards (Drexel University, Philadelphia), Yue Shen (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, MA), Michael A. Strauss (Princeton University, Princeton), Marianne Vestergaard (University of Arizona and Niels Bohr Institute, Copenhagen), and Fabian Walter (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy).

Parts of Xiaohui Fan's work were done when he was a long-term guest at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.mpia.deAll latest news from the category: Studies and Analyses

innovations-report maintains a wealth of in-depth studies and analyses from a variety of subject areas including business and finance, medicine and pharmacology, ecology and the environment, energy, communications and media, transportation, work, family and leisure.

Newest articles

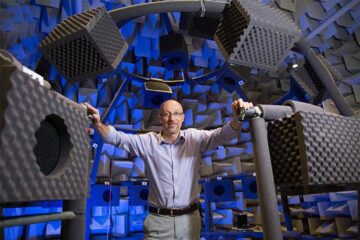

Why getting in touch with our ‘gerbil brain’ could help machines listen better

Macquarie University researchers have debunked a 75-year-old theory about how humans determine where sounds are coming from, and it could unlock the secret to creating a next generation of more…

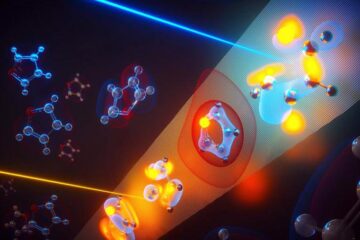

Attosecond core-level spectroscopy reveals real-time molecular dynamics

Chemical reactions are complex mechanisms. Many different dynamical processes are involved, affecting both the electrons and the nucleus of the present atoms. Very often the strongly coupled electron and nuclear…

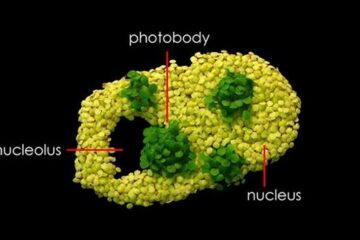

Free-forming organelles help plants adapt to climate change

Scientists uncover how plants “see” shades of light, temperature. Plants’ ability to sense light and temperature, and their ability to adapt to climate change, hinges on free-forming structures in their…