Dual character of excitons in the ultrafast regime: atomic-like or solid-like?

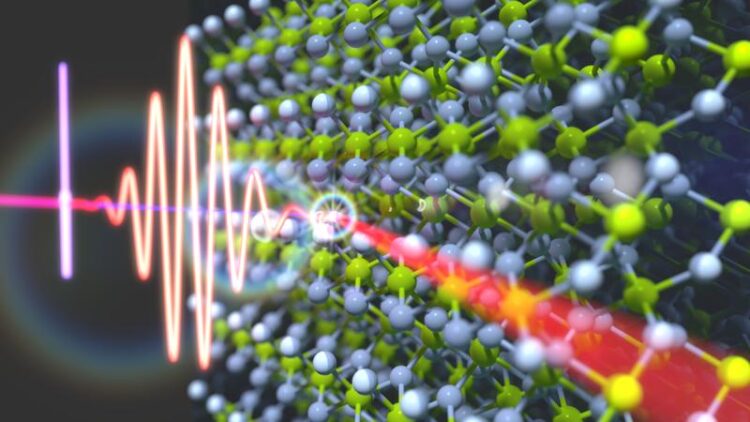

Light-induced ultrafast exciton dynamics in MgF₂ were investigated with attosecond transient reflection spectroscopy and microscopic theoretical simulations.

Matteo Lucchini, Politecnico di Milano

Excitons are quasiparticles which can transport energy through solid substances. This makes them important for the development of future materials and devices – but more research is needed to understand their fundamental behavior and how to manipulate it. Now an international research team involving theoreticians at the MPSD has discovered that an exciton can simultaneously adopt two radically different characters when it is stimulated by light. Their work, now published in Nature Communications, yields crucial new insights for current and future excitonics research.

Excitons consist of a negatively charged electron and a positively charged hole in solids. They are a so-called many-body-effect, produced by the interaction of many particles, especially when a strong light pulse hits the solid material. In the past decade, researchers have observed many-body-effects down to the unimaginably short attosecond timescale, in other words billionths of a billionth of a second.

However, scientists have still not reached a fundamental understanding of excitons and other many-body effects due to the complexity of the ultrafast electron dynamics when many particles interact. The research team from Politecnico di Milano, the University of Tsukuba and the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics (MPSD) wanted to explore the light-induced ultrafast exciton dynamics in MgF₂ single crystals by employing state-of-the-art attosecond transient reflection spectroscopy and microscopic theoretical simulations.

By combining these methods, the team discovered an entirely new property of excitons: The fact that they can simultaneously show atomic-like and solid-like characteristics. In excitons displaying an atomic character, the electrons and holes are tightly bound together by their Coulomb attraction – just like the electrons in atoms are bound by the nucleus. In excitons with a solid-like character, on the other hand, the electrons move more freely in solids, not unlike waves in the ocean.

These are significant findings, says lead author Matteo Lucchini from the Politecnico di Milano: “Understanding how excitons interact with light on these extreme time scales allows us to envision how to exploit their unique characteristics, fostering the establishment of a new class of electro-optical devices.”

During their attosecond experiment, the researchers managed to observe the sub-femtosecond dynamics of excitons for the first time, with signals consisting of slow and fast components. This phenomenon was explained with advanced theoretical simulations, adds co-author Shunsuke Sato from the MPSD and the University of Tsukuba: “Our calculations clarified that the slower component of the signal originates from the atomic-like character of the exciton while the faster component originates from the solid-like character – a significant discovery, which demonstrates the co-existence of the dual characters of excitons!”

This work opens up an important new avenue for the manipulation of excitonic as well as materials’ properties by light. It represents a major step towards the deep understanding of nonequilibrium electron dynamics in matter and provides the fundamental knowledge for the development of future ultrafast optoelectronic devices, electronics, optics, spintronics, and excitonics.

Wissenschaftliche Ansprechpartner:

Matteo Lucchini, lead author: matteo.lucchini@polimi.it

Originalpublikation:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-21345-7

Weitere Informationen:

https://www.mpsd.mpg.de/505793/2021-02-excitons-lucchini?c=17189

Media Contact

All latest news from the category:

Newest articles

Why getting in touch with our ‘gerbil brain’ could help machines listen better

Macquarie University researchers have debunked a 75-year-old theory about how humans determine where sounds are coming from, and it could unlock the secret to creating a next generation of more…

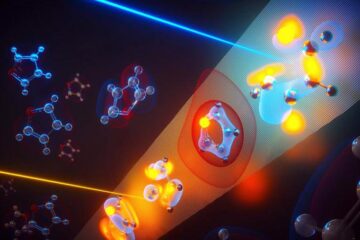

Attosecond core-level spectroscopy reveals real-time molecular dynamics

Chemical reactions are complex mechanisms. Many different dynamical processes are involved, affecting both the electrons and the nucleus of the present atoms. Very often the strongly coupled electron and nuclear…

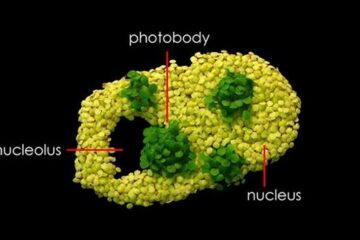

Free-forming organelles help plants adapt to climate change

Scientists uncover how plants “see” shades of light, temperature. Plants’ ability to sense light and temperature, and their ability to adapt to climate change, hinges on free-forming structures in their…