The goal: water-saving plants

Crops such as potatoes and sugar beets are much less tolerant to dry conditions compared to wild plants. “This is the result of plant breeding aimed at maximising yield,” says plant scientist Rainer Hedrich from the University of Würzburg. “Our high-performance plants have lost the natural stress tolerance of their early ancestors and have become dependent on artificial watering and fertilisation.”

How have wild plants acquired and maintained their drought tolerance within the course of Earth's history? Hedrich's team cooperated with Finnish colleagues from Tartu and Helsinki to look into this question. The scientists are searching for the answer deep inside the leaves of plants where they are analysing the molecular processes which the plants use to limit the loss of water.

How different plants handle dry conditions

Drought was not a problem for early algae and water plants. Having conquered the land in the course of evolution, however, they were confronted with sustained periods of drought. To survive these periods, early land plants such as mosses and ferns developed desiccation tolerance as early as 480 million years ago.

The key to this capability lies in abscisic acid (ABA), a plant hormone: In times of low water availability, the plants synthesise this stress hormone and thereby activate genes for special protective proteins, allowing them to survive significant water loss or even complete desiccation.

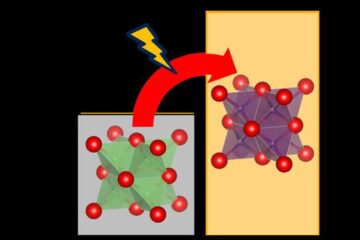

The flowering plants succeeding mosses and ferns in the course of evolution have a quite different approach to coping with drought: Their leaves have pores that can be closed to significantly reduce water loss. The microscopically small pores are each surrounded by two specialised guard cells. When the ABA stress hormone signalises drought, they reduce their cell pressure and thereby close the pore.

Signal chain at guard cell more complex than thought

In the past years, Hedrich's team has investigated the molecular details of the signal chain from synthesising the ABA hormone to closing the pores. A key role is attributed to channels located in the guard cells which release ions from these cells upon receiving a signal. As a result, the cell pressure sinks, the pores in the leaves close and the plant loses less water to the environment.

But the mechanism behind this water-saving “appliance” is even more complex than thought as Rainer Hedrich and Dietmar Geiger and colleagues report in the journal “Science Signaling”: because the channels not only respond to one specific signal but to multiple different signals.

Chemically, these signals are so-called phosphorylations. Different enzymes, the protein kinases, attach phosphate molecules to the channels (SLAC1) in different places thereby activating them. A kinase named OST1 plays a major role in this context: “When it is missing in plants, the guard cells no longer respond to the ABA hormone,” Geiger explains.

The goal: modifying the ON/OFF switch of the guard cells

In further biophysical analyses, the Würzburg researchers pinpointed the exact locations in which the SLAC1 channels can be switched on and off. By actuating these nanoswitches, which are single amino acids in the channel protein, the plant activates its channel proteins and thereby its water-saving mechanism.

In a next step, the scientists plan to modify this ON/OFF switch experimentally to manipulate the activity of the channels in the desired direction. Their long-term goal: growing crops with enhanced water-saving capability to better prepare them for the ongoing climate change that will entail longer dry periods. The researchers plan to conduct initial tests with potatoes and sugar beets.

Focus on the molecular evolution of drought tolerance

Hedrich's team is also investigating the evolution of drought tolerance: “We are presently cloning SLAC1 and OST1 relatives from algae, mosses, ferns and flowering plants,” he says. The ultimate goal is to clarify at what point the interaction between the two molecules formed in plants and when guard cells acquired the capability to control the opening of the leaf pores using the ABA hormone.

“Site- and kinase-specific phosphorylation-mediated activation of SLAC1, a guard cell anion channel stimulated by abscisic acid” Tobias Maierhofer, Marion Diekmann, Jan Niklas Offenborn, Christof Lind, Hubert Bauer, Kenji Hashimoto, Khaled A. S. Al-Rasheid, Sheng Luan, Jörg Kudla, Dietmar Geiger, and Rainer Hedrich. Science Signaling, 9 September 2014, DOI: 10.1126/scisignal.2005703

Contact

Prof. Dr. Rainer Hedrich, Department of Botany I of the University of Würzburg, Phone: +49 (0)931 31-86100, hedrich@botanik.uni-wuerzburg.de

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.uni-wuerzburg.deAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Webb captures top of iconic horsehead nebula in unprecedented detail

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has captured the sharpest infrared images to date of a zoomed-in portion of one of the most distinctive objects in our skies, the Horsehead Nebula….

Cost-effective, high-capacity, and cyclable lithium-ion battery cathodes

Charge-recharge cycling of lithium-superrich iron oxide, a cost-effective and high-capacity cathode for new-generation lithium-ion batteries, can be greatly improved by doping with readily available mineral elements. The energy capacity and…

Novel genetic plant regeneration approach

…without the application of phytohormones. Researchers develop a novel plant regeneration approach by modulating the expression of genes that control plant cell differentiation. For ages now, plants have been the…