Similar stem cells in insect and human gut

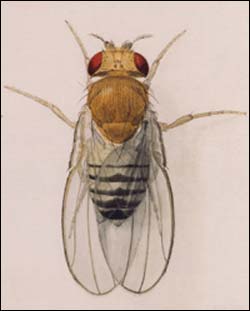

Watercolor illustration of Drosophila by Edith M. Wallace, Thomas Hunt Morgan’s illustrator. This image was published in C.B. Bridges and T.H. Morgan, Contributions to the Genetics of Drosophila melanogaster (Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution; 1919), CIW publication #278.

The six-legged fruitfly appears to have little in common with humans, but a new finding shows that they are really just tiny, distant cousins. Scientists at the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Embryology have found that adult fruitflies have the same stem cells controlling cell regulation in their gut as humans do. The research is important for understanding digestive disorders, including some cancers, and for developing cures. “The fact that fruitflies have the same genetic programming in their intestines as humans, strongly suggests that we were both cut from the same evolutionary cloth more than 500 million years ago,” stated lead author of the December 7, on-line Nature paper, Benjamin Ohlstein.

It may come as a surprise, but insects have the same basic structure to their gastrointestinal tract as vertebrates. They have a mouth, an esophagus, the equivalent to a stomach, and large and small intestines. The Carnegie researchers looked at their small intestines, where food is broken down into its constituent nutrients for the body to absorb. They focused on two cell types– cells that line the small and large intestines in a single layer to help break up and transport food molecules, called enterocytes; and cells that produce peptide hormones, some of whose functions include regulation of gastric motility as well as growth and differentiation of the gut (enteroendocrine cells).

In vertebrates, cells of the intestines are continually replenished by stem cells. Up to now, stem cells had not been observed in the gut of the fruitfly. To see if stem cells were at work, the researchers labeled each of the two cell types of interest and observed how successive generations of the cells transformed. They found for the first time that, like their vertebrate cousins, the fly cell types are replenished by stem cells. Moreover, like vertebrates, the stem cells are multipotent, which means that they can turn into different cell types, and Notch signaling is as essential in flies in controlling which intestinal cells form as it is in humans. Notch signaling was also found to instruct stem cells themselves, a role that has as yet to be identified for Notch signaling in vertebrates.

Allan Spradling, co-author, director of the Carnegie department, and a Howard Hughes Medical Investigator commented, “We’re excited because we know from previous experience that studying a process in a model system, such as the fruitfly, can greatly accelerate our understanding of the corresponding human process.”

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Sea slugs inspire highly stretchable biomedical sensor

USC Viterbi School of Engineering researcher Hangbo Zhao presents findings on highly stretchable and customizable microneedles for application in fields including neuroscience, tissue engineering, and wearable bioelectronics. The revolution in…

Twisting and binding matter waves with photons in a cavity

Precisely measuring the energy states of individual atoms has been a historical challenge for physicists due to atomic recoil. When an atom interacts with a photon, the atom “recoils” in…

Nanotubes, nanoparticles, and antibodies detect tiny amounts of fentanyl

New sensor is six orders of magnitude more sensitive than the next best thing. A research team at Pitt led by Alexander Star, a chemistry professor in the Kenneth P. Dietrich…