Two worms are better than one

Caenorhabditis elegans, a 1-mm soil-dwelling roundworm with 959 cells, may be the best-understood multicellular organism on the planet. As the most “pared-down” animal that shares essential features of human biology—from embryogenesis to aging—C. elegans is a favorite subject for studying how genes control these processes. The way these genes work in worms helps scientists understand how diseases like cancer and Alzheimer’s develop in humans when genes malfunction. With the publication of a genome sequence of C. eleganss’ first cousin, C. briggsae, Lincoln Stein and colleagues have greatly enhanced biologists’ ability to mine C. elegans for biological gold.

After confirming the accuracy of the sequence (it covers 98% of the genome and has an accuracy of 99.98%), the researchers turned to the substance of the genome. Examining the two worm genomes side by side, scientists can quickly spot genes and flag interesting regions for further investigation. Analyzing the organization of the two genomes, Stein et al. not only found strong evidence for roughly 1,300 new C. elegans genes, but also indications that certain regions could be “footprints of unknown functional elements.” While both worms have roughly the same number of genes (about 19,000), the C. briggsae genome has more repeated sequences, making its genome slightly larger. The size is estimated to be just over 100 million base pairs, about 1/30 the size of the human genome.

Because the worms set out on separate evolutionary paths about the same time mice and humans parted ways—about 100 million years ago, compared to 75 million years ago—the authors could compare how the two worm genomes have diverged with the divergence between mice and humans. The worms’ genomes, it seems, are evolving faster than their mammalian counterparts, based on the change in the size of the protein families (C. elegans has more chemosensory proteins than C. briggsae, for example), the rate of chromosomal rearrangements, and the rate at which silent mutations (DNA changes with no functional effect) accumulate in the genome. This would be expected, the researchers point out, because generations per year are a better measure of evolutionary rate than years themselves. (Generations in worms are about three days; in mice, about three months.)

What is surprising, they say, is that despite these genomic differences, the worms look nearly identical and occupy similar ecological niches; this is obviously not the case with humans and mice, which nevertheless have remarkably similar genomes. It’s the quality, rather than the quantity of the changes in the genome, that’s important. The nature of these changes, along with many other issues, can now be explored by searching the two species’ genomes and comparing those elements that have been conserved with those that have changed.

With the C. briggsae genome sequence in hand, worm biologists have a powerful new research tool. By comparing the genetic makeup of the two species, C. elegans researchers can refine their knowledge of this tiny human stand-in, fill in gaps about gene identity and function, as well as illuminate those functional elements that are harder to find, and study the nature and path of genome evolution.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

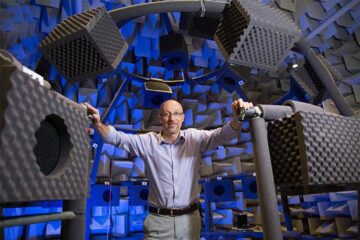

Why getting in touch with our ‘gerbil brain’ could help machines listen better

Macquarie University researchers have debunked a 75-year-old theory about how humans determine where sounds are coming from, and it could unlock the secret to creating a next generation of more…

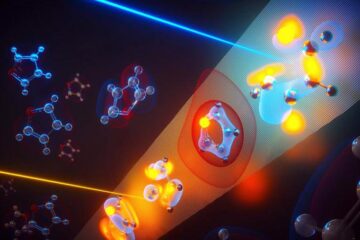

Attosecond core-level spectroscopy reveals real-time molecular dynamics

Chemical reactions are complex mechanisms. Many different dynamical processes are involved, affecting both the electrons and the nucleus of the present atoms. Very often the strongly coupled electron and nuclear…

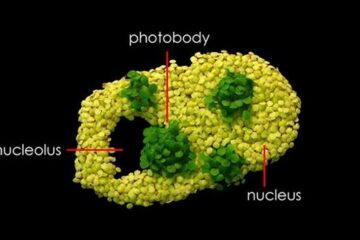

Free-forming organelles help plants adapt to climate change

Scientists uncover how plants “see” shades of light, temperature. Plants’ ability to sense light and temperature, and their ability to adapt to climate change, hinges on free-forming structures in their…