High-tech gel aids delivery of drugs

Gel aids delivery of drugs. Credit: Eben Alsberg

Eben Alsberg, the Richard and Loan Hill Professor of Bioengineering and Orthopaedics at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and colleagues report on a hydrogel-based carrier that can deliver siRNAs directly to where they are needed. They report their findings in Science Advances.

Other researchers have had some success in linking the siRNA molecules with other materials to form nanoparticles that help to prevent siRNA degradation and help the drugs enter cells.

But systemically delivered nanoparticle-incorporated drugs tend to have low rates of reaching targeted cells, necessitating multiple doses to have the desired effect, which increases the risk of negative side effects.

Biologically compatible hydrogels have been used to deliver biologics or drugs directly to specific areas in the body. A drug-infused hydrogel plug or sheet can be placed directly where the drug is needed — say in a joint or at a break in bone, or even injected.

But one problem has been that drugs loaded into hydrogels often diffuse out rapidly to surrounding cells and tissues, providing an initial burst of drug and not much more. The release can be delayed by changing the porosity of the hydrogel, its degradation rate and by tinkering with the affinity of the drug for the hydrogel.

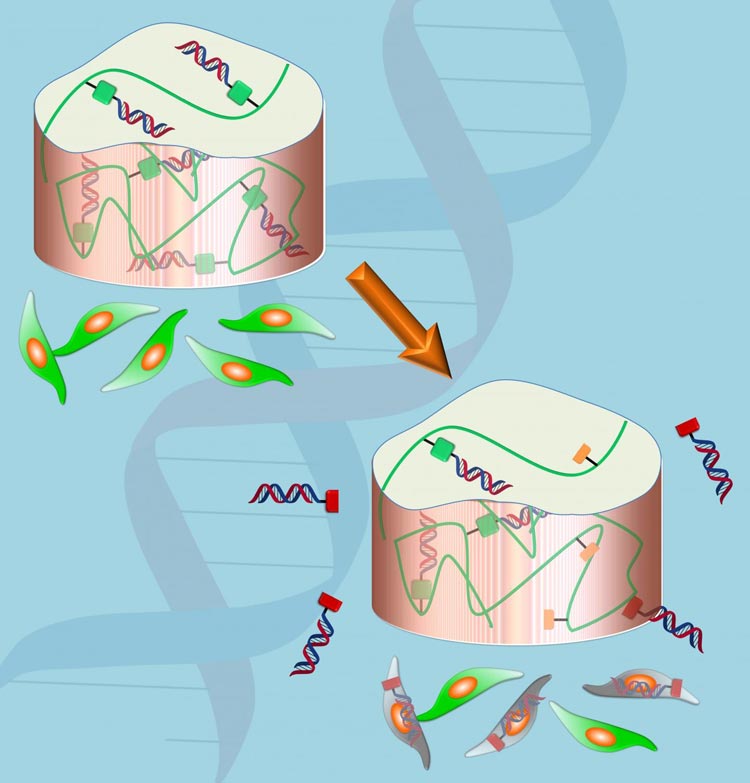

Alsberg together with Matthew Levy, associate professor of biochemistry at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and their colleagues developed a unique hydrogel strategy that allows for more control over the release of siRNAs over time. By chemically coupling the siRNA to the hydrogel via a linker that can degrade in the body, they can control the release of the drug.

When the hydrogel is placed in a water-based environment, such as a biological organism, water breaks the linker between the siRNA and the hydrogel, releasing the drug. In this kind of system, release of the drug is prolonged compared with when the siRNA is only physically trapped within the hydrogel.

“We may be able to use this technology in the future to, for example, prevent the production of certain proteins that are known to promote certain diseases, or to help transform stem cells into cells needed to repair damaged tissue such as bone or cartilage,” Alsberg said.

###

Cong Truc Huynh of UIC; Minh Khanh Nguyen, Alex Gilewski, and Nicholas Kwon of Case Western University; and Samantha E. Wilner and Keith E. Maier of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine are co-authors on the paper.

This research was supported by funding from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (R56DE022376), the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01AR069564, R01AR066193) the National Cancer Institute (R21CA182330), the Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (OR110196) and a Stand Up to Cancer Innovative Research Grant.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Sea slugs inspire highly stretchable biomedical sensor

USC Viterbi School of Engineering researcher Hangbo Zhao presents findings on highly stretchable and customizable microneedles for application in fields including neuroscience, tissue engineering, and wearable bioelectronics. The revolution in…

Twisting and binding matter waves with photons in a cavity

Precisely measuring the energy states of individual atoms has been a historical challenge for physicists due to atomic recoil. When an atom interacts with a photon, the atom “recoils” in…

Nanotubes, nanoparticles, and antibodies detect tiny amounts of fentanyl

New sensor is six orders of magnitude more sensitive than the next best thing. A research team at Pitt led by Alexander Star, a chemistry professor in the Kenneth P. Dietrich…