Antarctic Glaciers Surge When Ice Shelves Collapse

Antarctic glaciers that had been blocked behind the Larsen B ice shelf have been flowing more rapidly into the Weddell Sea, following the break-up of that shelf. Studies based on imagery from two satellites reached similar conclusions, which will be published September 22 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Researchers from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colorado, and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Greenbelt, Maryland, said the findings prove that ice shelves act as “brakes” on the glaciers that flow into them. The results also suggest that climate warming can lead to rapid sea level rise.

Large ice shelves in the Antarctic Peninsula disintegrated in 1995 and 2002, as a result of climate warming. Almost immediately after the 2002 Larsen B ice shelf collapse, researchers observed nearby glaciers flowing up to eight times faster than they did prior to the break-up. The speed-up also caused glacier elevations to drop, lowering them by up to 38 meters [125 feet] in six months.

“Glaciers in the Antarctic Peninsula accelerated in response to the removal of the Larsen B ice shelf,” said Eric J. Rignot, a JPL researcher who is lead author of one of the studies. “These two papers clearly illustrate, for the first time, the relationship between ice shelf collapses caused by climate warming and accelerated glacier flow.” Rignot’s study used data from the European Space Agency’s European Remote Sensing Satellites (ERS) and the Canadian Space Agency’s RADARSAT satellite.

“If anyone was waiting to find out whether Antarctica would respond quickly to climate warming, I think the answer is yes,” said Theodore A. (Ted) Scambos, an NSIDC glaciologist who is lead author of the second study. “We’ve seen 150 miles [240 kilometers] of coastline change drastically in just 15 years.” Scambos’s paper used data from Landsat 7 and ICESat, a NASA laser altimetry mission launched in 2003. Landsat 7 is jointly run by NASA and the United States Geological Survey.

The Rignot and Scambos papers illustrate relationships between climate change, ice shelf break-ups, and increased flow of ice from glaciers into the oceans. Increased flow of land ice into the oceans contributes to sea level rise. While the Larsen area glaciers are too small to affect sea level significantly, they offer insight into what will happen when climate change spreads to regions further south, where glaciers are much larger.

Scambos and his colleagues used five Landsat 7 images of the Antarctic Peninsula from before and after the Larsen B break-up. The images revealed crevasses on the surfaces of glaciers, which were used as markers in a computer-matching technique for tracking motion between image pairs. By following the patterns of crevasses from one image to the next, the researchers were able to calculate velocities of the glaciers. The surfaces of glaciers dropped rapidly as the flow sped up, according to ICESat measurements.

“The thinning of these glaciers was so dramatic that it was easily detected with ICESat, which can measure elevation changes to within an inch or two [several centimeters],” said Christopher A. Shuman, a GSFC researcher and a co-author on the Scambos paper. The Scambos study examined the period right after the Larsen B ice shelf collapse, to try to isolate the immediate effects of ice shelf loss on the glaciers.

Rignot’s study used RADARSAT to take monthly measurements that are ongoing. RADARSAT radar sends out signals and tracks their return after they bounce from snow and ice surfaces. Radar is not limited by clouds, while Landsat images require clear skies. RADARSAT can therefore provide continuous and broad velocity information of the ice.

According to Rignot’s study, the Hektoria, Green, and Evans glaciers flowed eight times faster in 2003 than they did in 2000. They slowed moderately in late 2003. The Jorum and Crane glaciers accelerated two-fold in early 2003 and three-fold by the end of 2003. Adjacent glaciers where the shelves remained intact showed no significant changes, according to both studies.

The studies were funded by NASA, the National Science Foundation, and the Instituto Antartico Argentino.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

A universal framework for spatial biology

SpatialData is a freely accessible tool to unify and integrate data from different omics technologies accounting for spatial information, which can provide holistic insights into health and disease. Biological processes…

How complex biological processes arise

A $20 million grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) will support the establishment and operation of the National Synthesis Center for Emergence in the Molecular and Cellular Sciences (NCEMS) at…

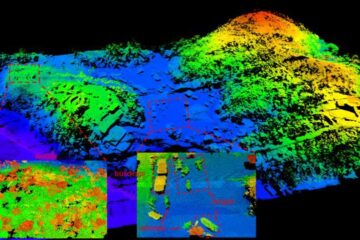

Airborne single-photon lidar system achieves high-resolution 3D imaging

Compact, low-power system opens doors for photon-efficient drone and satellite-based environmental monitoring and mapping. Researchers have developed a compact and lightweight single-photon airborne lidar system that can acquire high-resolution 3D…