UMass study reconsiders formation of Antarctic ice sheet

Findings detailed in Jan. 16 issue of Nature; greenhouse gases implicated

A study by University of Massachusetts Amherst geoscientist Robert DeConto posits an alternative theory regarding why Antarctica suddenly became glaciated 34 million years ago. The study challenges previous thinking about why the ice sheet formed and holds ramifications for the next several hundred years as greenhouse gases continue to rise. DeConto, who collaborated with David Pollard of Pennsylvania State University, has published the findings in the Jan. 16 issue of the journal Nature. The work was funded by the National Science Foundation.

“Scientists have long known that Antarctica was not always covered in a sheet of ice. Rather, the continent was once highly vegetated and populated with dinosaurs, with perhaps just a few Alpine glaciers and small ice caps in the continental interior,” DeConto explained. “In fact, the Antarctic peninsula is thought to have been a temperate rainforest.” Previous research on microfossils and ocean chemistry had already revealed that the Antarctic ice sheet may have developed over a period of just 50,000 years or even less, “the flip of a light switch in geologic terms,” said DeConto. The dramatic shift occurred at the cusp of the Eocene and Oligocene eras. “The question,” noted DeConto, “is why did it happen then, and why did it happen so quickly?”

A theory put forth in the 1970s suggested that plate tectonics was the driving force in Antarctic glaciation. “Pangea, the ’supercontinent,’ was breaking up. Australia was pulling away to the north, opening an ocean channel known as the Tasmanian passage.” Scientists theorized that as South America drifted away from the Antarctic Peninsula, the Drake passage opened. “This was thought to be the last barrier to an ocean current circumventing the continent. This current would have deflected warmer, northern waters and served to keep the continent chilled, and the Southern Oceans cool.” The theory was known as “thermal isolation.”

DeConto and Pollard wanted to determine how important the opening of the Southern Ocean passages actually was in the rapid glaciation of Antarctica. Among the factors they considered were: heat transport in the oceans; plate tectonics; carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere; and orbital variation. “We wanted to know whether the opening of ocean gateways was the primary cause of the glaciation, or whether the change was due to a combination of factors,” DeConto said.

The team turned to powerful computer technology in developing the new theory. Using computer simulations, the scientists essentially recreated the world of 34 million years ago, including a detailed topography of Antarctica and the placement of the drifting continents. Topography was particularly important, DeConto explained, because “if you have mountains that lift the snow into higher elevations, you have a better chance of maintaining snow all summer. This persistence is the key factor in formation of the ice sheet.”

The team then plugged in the factors previously mentioned: plate tectonics, climate, orbital variation, and the Earth’s procession. The computer played out the scenario for 10 million years, taking into account the gradual drop in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that is thought to have occurred in the Earth’s atmosphere during this period in Earth’s history. The scientists ran the simulation twice: “The two simulations were identical except in the second, a change in heat transport to replicate the opening of the Drake passage, to see how big an effect that gateway was.”

“This research points out the value of fundamental climate research,” said David Verardo, Director of the NSF’s Paleoclimate Program, which funded the research. “In short, DeConto and Pollard have shown, by using paleoclimatic models for a distant era, the power of atmospheric CO2 to produce rapid environmental change of gargantuan proportions. Furthermore, such effects can not be described by neat and simple regional patterns of variability.”

“Our study indicates that carbon dioxide is the critical factor,” DeConto said. “CO2 appears to be the factor that preconditions the system to become sensitive to other elements of the climate system. It was the first critical boundary and the determinant in the glaciation of the Antarctic continent.

“Carbon dioxide is a very important knob for changing climate, and is perhaps the fundamental control,”said DeConto. “This study indicates that the Earth’s climate is rapidly being pushed into a circumstance that hasn’t existed for a very long time; we’re returning to levels of carbon dioxide that have not been seen since before the Antarctic ice sheet.” This doesn’t mean that Antarctica is going to melt in the next 100 years, he noted, “but it’s important to be aware that the CO2 levels are rising very quickly.”

Note: Robert DeConto can be reached at 413-545-3426 or deconto@geo.umass.edu

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.umass.edu/All latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Webb captures top of iconic horsehead nebula in unprecedented detail

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has captured the sharpest infrared images to date of a zoomed-in portion of one of the most distinctive objects in our skies, the Horsehead Nebula….

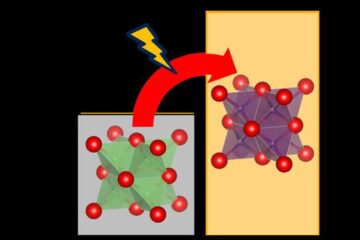

Cost-effective, high-capacity, and cyclable lithium-ion battery cathodes

Charge-recharge cycling of lithium-superrich iron oxide, a cost-effective and high-capacity cathode for new-generation lithium-ion batteries, can be greatly improved by doping with readily available mineral elements. The energy capacity and…

Novel genetic plant regeneration approach

…without the application of phytohormones. Researchers develop a novel plant regeneration approach by modulating the expression of genes that control plant cell differentiation. For ages now, plants have been the…