Slow but sure — Burned forest lands regenerate naturally

The research, to be published Wednesday in the Journal of Forestry by scientists from Oregon State University, examined the recovery of conifers on 35 plots that had burned in wildfires from 9 to 19 years ago, and generally found a high level of naturally-regenerating tree seedlings.

Although the abundance of natural regeneration appeared to be variable and growth often slow, there was no evidence of recent conifer mortality or suppression leading to seedling death.

Total conifer density and the types of tree species varied quite a bit depending on elevation, but the density of surviving conifer seedlings was as much or more than typical densities in 60-100 year old stands in this region, which is about 100 to 1,000 trees per acre. Traditional old growth forests of this region, with trees 250 or more years old, often had as few as 20-40 large trees per acre.

About 10 percent of the plots studied already had larger trees that were considered “free to grow” by forestry standards. The scientists said the height of competing shrubs had “quite likely” slowed after one or two decades, and “we predict that conifer mortality will remain low and height growth will accelerate as individuals continue to emerge above the shrub layer.” The study also showed that trees would regenerate at considerable distances from seed sources.

“The natural regeneration on many of these sites is actually much higher than needed to restore a forest,” said Jeff Shatford, a senior faculty research assistant in the OSU Department of Forest Science. “We expect that the high density of young trees we observed will thin out naturally over time.”

The authors said in their report that “assertions that burned areas, left unmanaged, will remain unproductive for some indefinite period, seem unwarranted.” Short term delays in conifer regeneration and a broader range of recovering plant and animal species may also have benefits in terms of varied tree size, plant biodiversity, and wildlife habitat.

“When left to natural regeneration in this region, it appears that conifers may come back more slowly and with more variation than with conventional forest management, but in most cases they do come back,” said David Hibbs, co-author of the report and a professor of forest ecology and silviculture in the OSU Department of Forest Science. “There may be some cases, especially on the lowest, hottest, south-facing slopes, where that is not true. But at most elevations and in most situations, natural conifer regeneration appears to be working.”

Whether lands should be planted and weed competition controlled is more a question of short-term timber production, tree species control and forest management goals than the regeneration of the forest, the scientists said.

The sites picked for this study all met several criteria – they had gone through a hot, canopy-replacing wildfire from 9-19 years ago, more than 90 percent of the trees were killed in the fire, and there was no post-fire salvage logging or tree planting. The sites were on the Klamath, Rogue/Siskiyou or Umpqua National Forests.

Conifer trees that naturally regenerated were dominated by Douglas-fir and ponderosa pine at lower elevations, and true firs at higher elevations. There was considerable variation in the regeneration process. Some sites filled in immediately. Others had a few years delay, then rapid filling; some were slow but constant; and a few sites never filled. Surprising to researchers was that up to 19 years after a fire, there was still some new and locally dominant conifer regeneration.

Seed was provided by patches of surviving trees or nearby unburned forest, which were rarely more than a few hundred yards from fire-killed trees. The relationship of shrub competition with tree seedlings also was surprising. On low and middle elevation sites, there were actually more conifers where there was more shrub and hardwood cover – what favored one group also seemed to favor the other. At higher elevations, shrub cover was less of an issue and the abundance of conifer regeneration was conspicuously high. At some high elevation sites, trees continued to establish in great numbers even many years after the fire.

In continued research, OSU scientists said they plan to study more specifically what sites will grow into mature forests and what species will persist there, and also more directly compare the progress of natural regeneration with that of managed sites.

This study was funded by the Joint Fire Science Program, a partnership of six federal wildland, fire and research organizations.

Fire suppression and fuel buildups, among other possible causes, have led to an increasing frequency and severity of forest fire in the western United States, the researchers said. Between 1970 and 2004, more than 600 wildfires burned over 20 million acres in Oregon and California. The 2002 Biscuit Fire, in terrain similar to where this research was done, was one of the largest fires in Oregon’s recorded history.

The recovery of burned lands after wildfire, and whether active management is necessary, has become a point of considerable interest and controversy in recent years. Some studies have argued that, in the absence of aggressive management, burned areas might turn into unproductive shrub fields that could persist for decades or centuries.

“In contrast to expectations, we found natural conifer regeneration to be generally abundant across a variety of settings,” the scientists wrote in the new study. “Management plans can benefit greatly from utilizing natural conifer regeneration, but managers must face the challenge of long regeneration periods, and be able to accommodate high levels of variation across the landscape of a fire.”

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.oregonstate.eduAll latest news from the category: Agricultural and Forestry Science

Newest articles

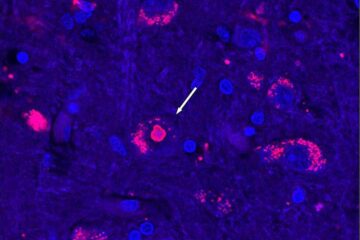

After 25 years, researchers uncover genetic cause of rare neurological disease

Some families call it a trial of faith. Others just call it a curse. The progressive neurological disease known as spinocerebellar ataxia 4 (SCA4) is a rare condition, but its…

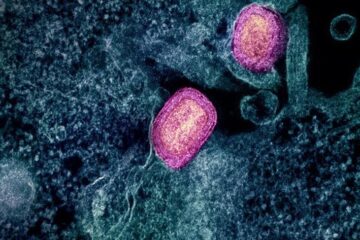

Lower dose of mpox vaccine is safe

… and generates six-week antibody response equivalent to standard regimen. Study highlights need for defined markers of mpox immunity to inform public health use. A dose-sparing intradermal mpox vaccination regimen…

Efficient, sustainable and cost-effective hybrid energy storage system for modern power grids

EU project HyFlow: Over three years of research, the consortium of the EU project HyFlow has successfully developed a highly efficient, sustainable, and cost-effective hybrid energy storage system (HESS) that…