Low-cost, ultra-fast DNA sequencing brings diagnostic use closer

Sequencing DNA could get a lot faster and cheaper – and thus closer to routine use in clinical diagnostics – thanks to a new method developed by a research team based at Boston University. The team has demonstrated the first use of solid state nanopores — tiny holes in silicon chips that detect DNA molecules as they pass through the pore — to read the identity of the four nucleotides that encode each DNA molecule. In addition, the researchers have shown the viability of a novel, more efficient method to detect single DNA molecules in nanopores.

“We have employed, for the first time, an optically-based method for DNA sequence readout combined with the nanopore system,” said Boston University biomedical engineer Amit Meller, who collaborated with other researchers at Boston University, and at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester. “This allows us to probe multiple pores simultaneously using a single fast digital camera. Thus our method can be scaled up vastly, allowing us to obtain unprecedented DNA sequencing throughput.”

The research is detailed in Nano Letters [http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/nl1012147]. The National Institutes of Health are currently considering a four-year grant application to further advance Meller's nanopore sequencing project.

This low-cost, ultra-fast DNA sequencing could revolutionize both healthcare and biomedical research, and lead to major advances in drug development, preventative medicine and personalized medicine. By gaining access to the entire sequence of a patient's genome, a physician could determine the probability of that patient developing a specific genetic disease.

The team's findings show that nanopores, which can analyze extremely long DNA molecules with superior precision, are uniquely positioned to compete with current, third-generation DNA sequencing methods for cost, speed and accuracy. Unlike those approaches, the new nanopore method does not rely on enzymes whose activity limits the rate at which DNA sequences can be read.

“This puts us in the unique advantageous position of being able to claim that our sequencing method is as fast as the rapidly evolving photographic technologies,” said Meller. “We currently have the capability of reading out about 200 bases per second, which is already much faster than other commercial third-generation methods. This is only the starting point for us, and we expect to increase this rate by up to a factor of four in the next year.” Licensing intellectual property from Boston University and Harvard University, Meller and his collaborators recently founded NobleGen Biosciences to develop and commercialize nanopore sequencing based on the new method.

“I believe that it will take three to five years to bring cheap DNA sequencing to the medical marketplace, assuming an aggressive research and development program is in place,” said Meller.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.bu.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

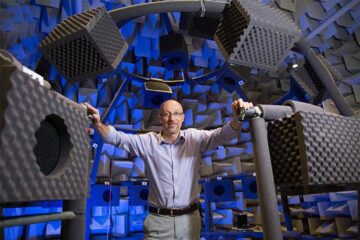

Why getting in touch with our ‘gerbil brain’ could help machines listen better

Macquarie University researchers have debunked a 75-year-old theory about how humans determine where sounds are coming from, and it could unlock the secret to creating a next generation of more…

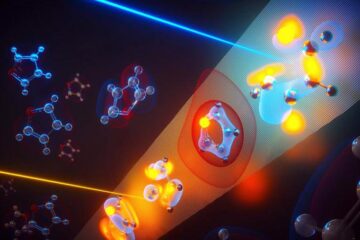

Attosecond core-level spectroscopy reveals real-time molecular dynamics

Chemical reactions are complex mechanisms. Many different dynamical processes are involved, affecting both the electrons and the nucleus of the present atoms. Very often the strongly coupled electron and nuclear…

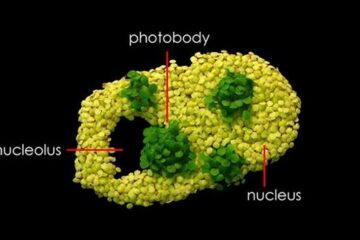

Free-forming organelles help plants adapt to climate change

Scientists uncover how plants “see” shades of light, temperature. Plants’ ability to sense light and temperature, and their ability to adapt to climate change, hinges on free-forming structures in their…