Fine-tuning gene expression during stress recovery

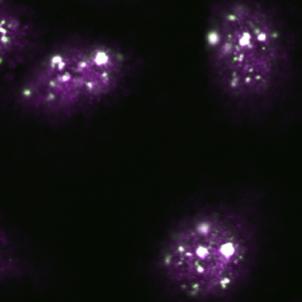

Nuclear stress bodies (white) formed in response to heat stress. Credit: Hokkaido University Usage Restrictions: This image is copyrighted and can be used for reporting this research work without obtaining a permission if credited properly.

Hokkaido University researchers are beginning to uncover the functions of mysterious organelles in the nucleus and their relation to stress, 30 years after their discovery.

The organelles, called nuclear stress bodies, form when cells are exposed to heat or chemical stress. When conditions return to normal, the organelles promote retention of RNA segments, called introns, the researchers report in The EMBO Journal.

This is important because intron retention regulates gene expression for a variety of biological functions, including stress response, cell division, learning and memory, preventing the accumulation of damaged DNA, and even tumour growth.

Among their many mysteries, nuclear stress bodies were found to assemble on a type of long non-coding RNA in response to heat and chemical stress. Molecular biologist Tetsuro Hirose of Hokkaido University's Institute for Genetic Medicine specializes in non-coding RNAs, which are molecules copied from DNA, but not translated into proteins.

Hirose and his colleagues investigated the functions of nuclear stress bodies by turning off the long non-coding RNA and thus removing them from human cells.

Removing the nuclear stress bodies resulted in a vast suppression of intron retention during stress recovery. Further investigation enabled the team, which included researchers from Hokkaido University, the National Institute for Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, and the University of Tokyo in Japan, to understand how nuclear stress bodies, when they are present, help cells recover from stress.

Here is what they found: Heat stress at 42°C leads to de-phosphorylation of splicing factors called SRSFs, resulting in the removal of specific introns and the production of mature RNA molecules.

Simultaneously, de-phosphorylated SRSFs become incorporated in the nuclear stress bodies. As soon as cells return to the body's normal temperature of 37°C, nuclear stress bodies recruit an enzyme to re-phosphorylate SRSFs, therefore rapidly restoring intron retention to its normal levels.

“Nuclear stress bodies probably function to fine-tune gene expressions by rapidly restoring the proper levels of intron-retaining messenger RNAs as the cell recovers from stress,” Tetsuro Hirose says. Further studies are needed to reveal the specific effects of intron retention after heat stress, and to understand the detail mechanism of the process.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

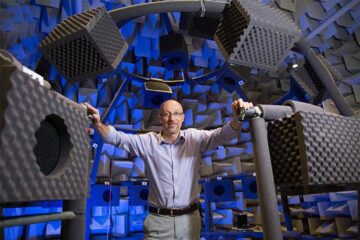

Why getting in touch with our ‘gerbil brain’ could help machines listen better

Macquarie University researchers have debunked a 75-year-old theory about how humans determine where sounds are coming from, and it could unlock the secret to creating a next generation of more…

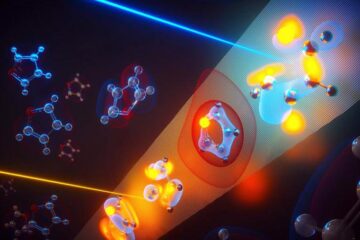

Attosecond core-level spectroscopy reveals real-time molecular dynamics

Chemical reactions are complex mechanisms. Many different dynamical processes are involved, affecting both the electrons and the nucleus of the present atoms. Very often the strongly coupled electron and nuclear…

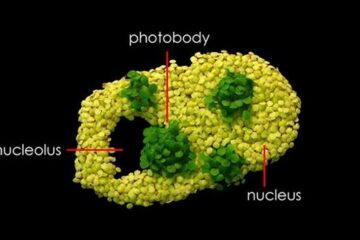

Free-forming organelles help plants adapt to climate change

Scientists uncover how plants “see” shades of light, temperature. Plants’ ability to sense light and temperature, and their ability to adapt to climate change, hinges on free-forming structures in their…