Dengue Virus Turns On Mosquito Genes That Make Them Hungrier

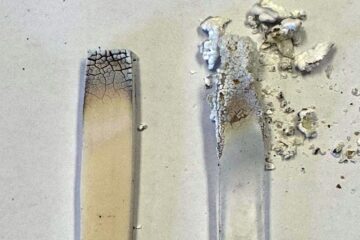

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health<br>Picture shows the presence of the dengue virus in the mosquitoes chemosensory (antennae and palp) and feeding organs (proboscis).<br>PLoS Pathogens (March 29, 2012)<br>

Specifically, they found that dengue virus infection of the mosquito’s salivary gland triggered a response that involved genes of the insect’s immune system, feeding behavior and the mosquito’s ability to sense odors. The researchers findings are published in the March 29 edition of PLoS Pathogens.

Dengue virus is primarily spread to people by the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Over 2.5 billion people live in areas where dengue fever is endemic. The World Health Organization estimates that there are between 50 million and 100 million dengue infections each year.

“Our study shows that the dengue virus infects mosquito organs, the salivary glands and antennae that are essential for finding and feeding on a human host. This infection induces odorant-binding protein genes, which enable the mosquito to sense odors. The virus may, therefore, facilitate the mosquito’s host-seeking ability, and could—at least theoretically—increase transmission efficiency, although we don’t fully understand the relationships between feeding efficiency and virus transmission,” said George Dimopoulus, PhD, senior author of the study and professor with the Bloomberg School’s Malaria Research Institute. “In other words, a hungrier mosquito with a better ability to sense food is more likely to spread dengue virus.”

For the study, researchers performed a genome-wide microarray gene expression analysis of dengue-infected mosquitoes. Infection regulated 147 genes with predicted functions in various processes including virus transmission, immunity, blood-feeding and host-seeking. Further analysis of infected mosquitoes showed that silencing, or “switching off,” two odorant-binding protein genes resulted in an overall reduction in the mosquito’s blood-acquisition capacity from a single host by increasing the time it took the for mosquito to probe for a meal.

“We have, for the first time shown, that a human pathogen can modulate feeding-related genes and behavior of its vector mosquito, and the impact of this on transmission of disease could be significant,” said Dimopoulos.

“Dengue virus infection of the Aedes aegypti salivary gland and chemosensory apparatus induces genes that modulate infection and blood-feeding behavior” was written by Shuzhen Sim, Jose L. Ramirez and George Dimopoulos.

Funding for the research was provided by National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease at the National Institutes of Health.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.jhsph.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Trotting robots reveal emergence of animal gait transitions

A four-legged robot trained with machine learning by EPFL researchers has learned to avoid falls by spontaneously switching between walking, trotting, and pronking – a milestone for roboticists as well…

Innovation promises to prevent power pole-top fires

Engineers in Australia have found a new way to make power-pole insulators resistant to fire and electrical sparking, promising to prevent dangerous pole-top fires and reduce blackouts. Pole-top fires pose…

Possible alternative to antibiotics produced by bacteria

Antibacterial substance from staphylococci discovered with new mechanism of action against natural competitors. Many bacteria produce substances to gain an advantage over competitors in their highly competitive natural environment. Researchers…