Bilinguals kick out their tongues

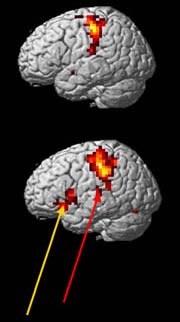

Bilingual brains (bottom) react to words differently than monolingual brains (top). <br>© T. Muente <br>

Linguists filter languages for sound before meaning.

Bilingual people switch off one language to avoid speaking double Dutch. By first sounding out words in their brain’s dictionary, they may stop one tongue from interfering with another.

Those fluent in two languages rarely mix them up. They switch between language filters that oust foreign words, Thomas Munte of Otto von Guericke University in Magdeburg, Germany, and his team suggest1.

Their studies of brain activity reveal that bilinguals reject words that are not part of the language they are speaking – before working out what the words mean. “They could completely ignore the other language,” says Munte, and so prevent the two from merging.

With two languages in store, it has long been thought that one must be suppressed when the other is read or spoken. Previously, neuroscientists debated whether the two are processed in different areas of the brain.

But functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of brain activity cannot distinguish between two small populations of nerves in the same general area, explains Cathy Price who studies brain anatomy at University College London.

The new study suggests that timing rather than space is important. As well as fMRI, Munte’s team measured the brain’s electrical signals for a second after people were shown a word. By tracking activity in space and time the group is “taking a new perspective”, says Price.

Different nerve circuits carrying the two languages will ultimately be found, thinks David Green who investigates language processing at University College London. The question will then be how they are controlled. “We’re only at the beginning,” he says. Exercises that train these control regions might one day be useful language lessons.

Say the word

Munte’s team examined people fluent in Spanish and Catalan, a language of north-eastern Spain. The subjects picked out real Spanish words from a list of Spanish, Catalan or pseudowords such as ’amigi’.

Common Catalan words produced the same brain activity as uncommon ones in bilinguals. Fluent monolingual readers jump straight from the familiar word ’dog’, to a stored concept of a dog. Bilinguals appear not to access a word’s meaning before rejecting it.

Bilinguals use a different processing pathway, the team suggests, which sounds out the word first. The fMRI images showed that a brain area involved in spelling out letters is active when rejecting Catalan and pseudowords. The pronunciation rules of Spanish or Catalan might work as a filter, recognizing words in the inappropriate language. Speakers switch filters when they switch between languages.

References

- Rodriguez-Fornells, A., Rotte, M., Heinze, H.-J., Nosselt, T. & Munte, T.F. Brain potential and functional MRI evidence for how to handle two languages with one brain. Nature, 415, 1026 – 1029, (2002).

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Interdisciplinary Research

News and developments from the field of interdisciplinary research.

Among other topics, you can find stimulating reports and articles related to microsystems, emotions research, futures research and stratospheric research.

Newest articles

Sea slugs inspire highly stretchable biomedical sensor

USC Viterbi School of Engineering researcher Hangbo Zhao presents findings on highly stretchable and customizable microneedles for application in fields including neuroscience, tissue engineering, and wearable bioelectronics. The revolution in…

Twisting and binding matter waves with photons in a cavity

Precisely measuring the energy states of individual atoms has been a historical challenge for physicists due to atomic recoil. When an atom interacts with a photon, the atom “recoils” in…

Nanotubes, nanoparticles, and antibodies detect tiny amounts of fentanyl

New sensor is six orders of magnitude more sensitive than the next best thing. A research team at Pitt led by Alexander Star, a chemistry professor in the Kenneth P. Dietrich…