NASA'S Cassini spacecraft captures Saturnian moon ballet

Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute Released: June 21, 2006 (PIA 07787)

In addition to their drama and visual interest, scientists use these movies to refine their understanding of the orbits of Saturn's moons. Engineers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., use the same images, and the orbital positions of the moons, to help them navigate the Cassini spacecraft, which is nearing the halfway mark of its four-year tour.

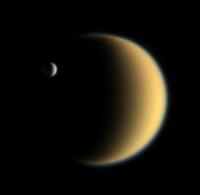

Pictures capturing several moons in one frame are often strikingly beautiful, especially when deliberately imaged in red, green and blue spectral filters, which allow scientists to create a color photo. One recent color image shows two of Saturn's most fascinating moons, icy-white Enceladus and orange, haze-enshrouded Titan.

Caption: Many denizens of the Saturn system wear a uniformly gray mantle of darkened ice, but not so for these two most fascinating of moons. The brightest body in the Solar System, Enceladus, is contrasted here against Titan's smoggy golden murk.

Ironically, what these two moons hold in common gives rise to their starkly contrasting colors. Both bodies are, to varying degrees, geologically active. For Enceladus, its southern polar vents emit a spray of icy particles that coats the small moon, giving it a clean, white veneer. On Titan, as-yet-undefined processes are supplying the atmosphere with methane and other chemicals that are broken down by sunlight, creating the thick yellow-orange haze that suffuses the atmosphere and, over geologic time, falls and coats the surface.

The thin, bluish haze along Titan’s limb is caused when sunlight is scattered by haze particles roughly the same size as the wavelength of blue light, or around 400 nanometers.

Images taken using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to create this natural color view. The images were obtained on Feb. 5, 2006 using the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera at a distance of 4.1 million kilometers (2.5 million miles) from Enceladus and 5.3 million kilometers (3.3 miles) from Titan. Resolution in the original images was 25 kilometers (16 miles) per pixel on Enceladus and 32 kilometers (20 miles) per pixel on Titan. The view has been magnified by a factor of two.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the Cassini-Huygens mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C. The imaging team consists of scientists from the US, England, France, and Germany. The imaging operations center and team lead (Dr. C. Porco) are based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

Sea slugs inspire highly stretchable biomedical sensor

USC Viterbi School of Engineering researcher Hangbo Zhao presents findings on highly stretchable and customizable microneedles for application in fields including neuroscience, tissue engineering, and wearable bioelectronics. The revolution in…

Twisting and binding matter waves with photons in a cavity

Precisely measuring the energy states of individual atoms has been a historical challenge for physicists due to atomic recoil. When an atom interacts with a photon, the atom “recoils” in…

Nanotubes, nanoparticles, and antibodies detect tiny amounts of fentanyl

New sensor is six orders of magnitude more sensitive than the next best thing. A research team at Pitt led by Alexander Star, a chemistry professor in the Kenneth P. Dietrich…