Molecular milk mayonnaise: How mouthfeel and microscopic properties are related in mayonnaise

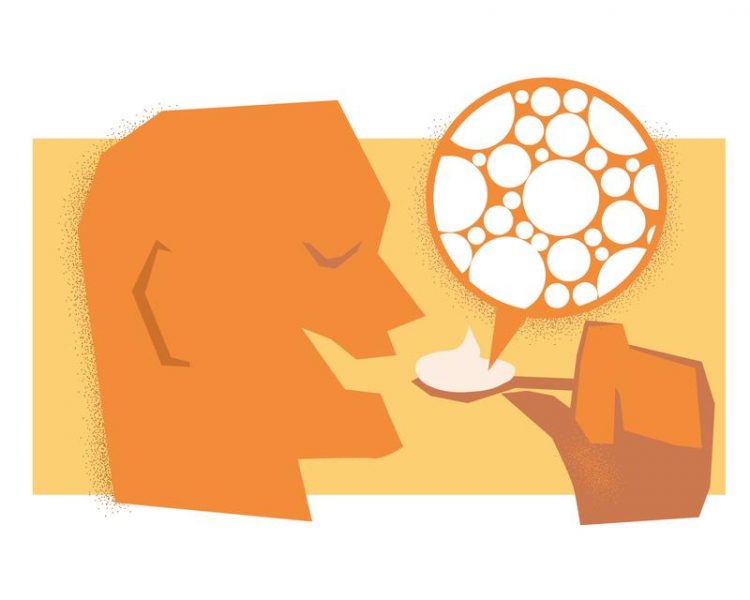

Small oil droplets are formed in the milk mayonnaise, the size and arrangement of these droplets being largely responsible for the consistency of the mayonnaise. © MPI-P

Milk mayonnaise can also be made at home simply by mixing oil with milk using a mixer. At the molecular level, the two emulsifiers casein and whey play an important role here: they ensure that oil can dissolve well in the milk, which consists mainly of water.

Whey, for example, is a molecule that is present in raw milk in a folded or crumpled state. When a milk-oil mixture is whipped with a mixer, this molecule unfolds and can form a boundary layer around the oil, embedding small oil droplets in the aqueous milk. The result is a mayonnaise.

The size of these oil droplets determines significantly how creamy the mayonnaise feels in the mouth at the end. “We were able to show that the size of the droplets is directly related to the mixing ratio between oil and milk,” said Thomas Vilgis, group leader of the “Food Science” group in Prof. Kurt Kremer's department.

“Size and number have a direct influence on how freely a single oil droplet can move or how strongly it is trapped between other droplets.”

Smaller droplets can be much closer together. So if you look at only one droplet, it is trapped by other, closely adjacent droplets – a kind of cage is formed. This makes it increasingly difficult for the oil droplet to move. As a result, the mayonnaise becomes stiffer.

Only with sufficient force on the individual drops – as it is exercised e.g. with the tongue with the meal – the droplets can free themselves from their cage and begin to flow against each other: The originally stiff mayonnaise becomes creamy. These processes can be observed directly in the laboratory using microscopy with simultaneous shearing, i.e. mechanical stress – so-called “rheo-optics”.

“We were able to show that a minimum oil content of 68% is required for a solid mayonnaise, the creamiest being with 73% oil,” says Vilgis. “If you want to stabilize the mayonnaise even more, you can heat it to 65 – 70 degrees.”

When the mayonnaise is heated, the whey proteins surrounding the oil droplets form free binding sites that connect with neighbouring whey proteins – similar to puzzle pieces that join together with other puzzle pieces to form a picture. In the process, the oil droplets are fixed in a protein net.

According to Vilgis, the mass produced in this way has the texture of a soft, creamy yet gelled pudding rather than that of mayonnaise, but still consists of the same ingredients.

The scientists have now published their results in the scientific journal “Food”.

Prof. Dr. Thomas Vilgis

Phone: 0+49 6131 379-143

Mail: thomas.vilgis@mpip-mainz.mpg.de

Katja Braun, Andreas Hanewald, and Thomas A. Vilgis

Milk Emulsions: Structure and Stability

Foods 2019, 8(10), 483

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/foods8100483

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.mpip-mainz.mpg.deAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Microscopic basis of a new form of quantum magnetism

Not all magnets are the same. When we think of magnetism, we often think of magnets that stick to a refrigerator’s door. For these types of magnets, the electronic interactions…

An epigenome editing toolkit to dissect the mechanisms of gene regulation

A study from the Hackett group at EMBL Rome led to the development of a powerful epigenetic editing technology, which unlocks the ability to precisely program chromatin modifications. Understanding how…

NASA selects UF mission to better track the Earth’s water and ice

NASA has selected a team of University of Florida aerospace engineers to pursue a groundbreaking $12 million mission aimed at improving the way we track changes in Earth’s structures, such…