Motor memory: The long and short of it

For the first time, scientists at USC have unlocked a mechanism behind the way short- and long-term motor memory work together and compete against one another.

The research — from a team led by Nicolas Schweighofer of the Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy at USC — could potentially pave the way to more effective rehabilitation for stroke patients.

It turns out that the phenomenon of motor memory is actually the product of two processes: short-term and long-term memory.

If you focus on learning motor skills sequentially — for example, two overhand ball throws — you will acquire each fairly quickly, but are more likely to forget them later. However, if you split your time up between learning multiple motor skills — say, learning two different throws — you will learn them more slowly but be more likely to remember them both later.

This phenomenon, called the “contextual interference effect,” is the result of a showdown between your short-term and long-term motor memory, Schweighofer said. Though scientists have long been aware of the effect's existence, Schweighofer's research is the first to explain the mechanism behind it.

“Continually wiping out motor short-term memory helps update long-term memory,” he said.

In short, if your brain can rely on your short-term motor memory to handle memorizing a single motor task, then it will do so, failing to engage your long-term memory in the process. If you deny your brain that option by continually switching from learning one task to the other, your long-term memory will kick in instead. It will take longer to learn both, but you won't forget them later.

“It is much more difficult for people to learn two tasks,” he said. “But in the random training there was no significant forgetting.”

Schweighofer uncovered the mechanism while exploring the puzzling results of spatial working memory tests in individuals who had suffered a brain stroke.

Those individuals, whose short-term memory is damaged from the stroke, show better long-term retention because they are forced to rely on their long-term memories.

Schweighofer's paper appears in the August issue of Journal of Neurophysiology.

In the long term, he said he hopes this research could help lead to computer programs that optimize rehabilitation for stroke patients, determining what method of training will work best for each individual.

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.usc.eduAll latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

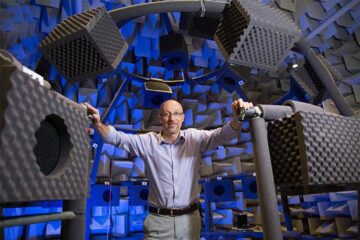

Why getting in touch with our ‘gerbil brain’ could help machines listen better

Macquarie University researchers have debunked a 75-year-old theory about how humans determine where sounds are coming from, and it could unlock the secret to creating a next generation of more…

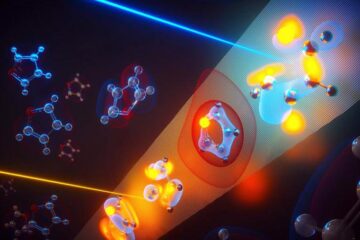

Attosecond core-level spectroscopy reveals real-time molecular dynamics

Chemical reactions are complex mechanisms. Many different dynamical processes are involved, affecting both the electrons and the nucleus of the present atoms. Very often the strongly coupled electron and nuclear…

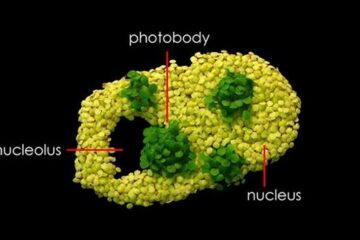

Free-forming organelles help plants adapt to climate change

Scientists uncover how plants “see” shades of light, temperature. Plants’ ability to sense light and temperature, and their ability to adapt to climate change, hinges on free-forming structures in their…