Towards a new design paradigm for high-performance catalysts

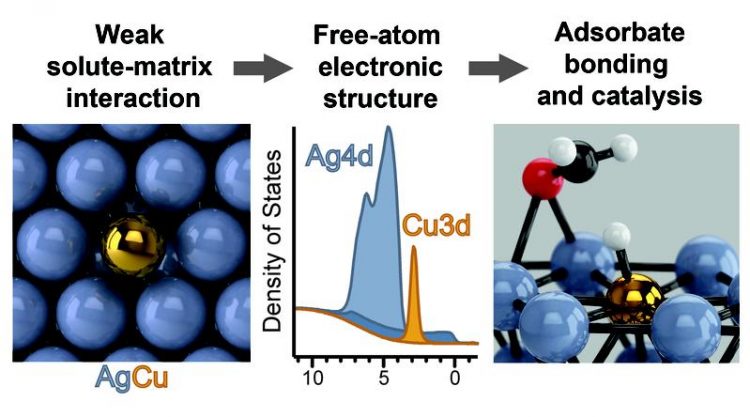

Illustration of an isolated-atom alloy Nature Chemistry

The chemical industry relies on high-performance catalysts to produce the chemicals used by society – such as fuels, plastics and medicines. Some chemicals cannot be efficiently produced because the needed catalysts have not yet been discovered. A great deal of contemporary research is aimed at designing novel catalysts to fulfill these roles.

Recently reported in the journal Nature Chemistry, Greiner, Jones and Co. discovered a phenomenon that occurs in metal alloys that could yield a new design paradigm for high-performance catalysts.

The team of researchers found that when adding a very small amount of one metal to another, the minority element’s properties can change drastically, altering how it interacts with molecules. This finding is of particular interest to chemical industry, where the efficiency of chemical production often depends on how molecules interact with metal catalysts.

The team found that a dilute mixture of copper in silver results in certain properties that resemble free isolated atoms. Nature uses isolated metal atoms in biological catalysts called enzymes. These finely tuned catalysts are known for their unparalleled catalytic efficiency.

However, industrial catalysts have yet to capitalize on this phenomenon because they require much harsher conditions than biological systems can tolerate. Industrial catalysis must instead rely on less efficient inorganic materials in the form of macroscopic particles. By taking advantage of the properties of isolated atoms, there is the potential that catalytic efficiencies of industrial catalysts could rival biological systems.

Jones and Greiner made use of the recently developed concept of “single-atom alloys–alloys” in which the minority element forms no bonds to other minority element atoms. Using such materials, they showed experimentally that certain single-atom alloys exhibit properties that resemble isolated ions.

With theoretical calculations, they showed that a number of metal combinations should also give rise to this behavior, representing a class of hitherto unexplored class of materials whose catalytic properties can be tuned. These findings could open up a new paradigm for designing novel high-performance catalysts.

Dr. Mark Greiner

Max Planck Institute for Chemical Energy Conversion

Phone: +49 (0)-208-306-3686

E-mail: Mark.Greiner@cec.mpg.de

Dr. Travis Jones

Fritz-Haber Institute of the Max-Planck Society

Phone: +49 (0)-30-8413-4421

E-Mail: trjones@fhi-berlin.mpg.de

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41557-018-0125-5

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41557-018-0143-3

http://www.cec.mpg.de

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Sea slugs inspire highly stretchable biomedical sensor

USC Viterbi School of Engineering researcher Hangbo Zhao presents findings on highly stretchable and customizable microneedles for application in fields including neuroscience, tissue engineering, and wearable bioelectronics. The revolution in…

Twisting and binding matter waves with photons in a cavity

Precisely measuring the energy states of individual atoms has been a historical challenge for physicists due to atomic recoil. When an atom interacts with a photon, the atom “recoils” in…

Nanotubes, nanoparticles, and antibodies detect tiny amounts of fentanyl

New sensor is six orders of magnitude more sensitive than the next best thing. A research team at Pitt led by Alexander Star, a chemistry professor in the Kenneth P. Dietrich…