Plant clock gene also works in human cells

“It's surprising to find a clock gene that is performing the same function across such widely unrelated groups,” said Stacey Harmer, associate professor of plant biology in the UC Davis College of Biological Sciences and senior author on the paper.

Major groups of living things — plants, animals and fungi — all have circadian clocks that work in similar ways but are built from different pieces, Harmer said. The newly identified gene is an exception to that.

Harmer and UC Davis postdoctoral scholar Matthew Jones, with colleagues at Rice University in Houston and the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, identified the “Jumonji-containing domain 5 gene,” or JMJD5, from the lab plant Arabidopsis by screening existing databases for genes that were switched on along with the central plant clock gene, TOC1.

JMJD5 stood out. The protein made by the gene can carry out chemical modification of the histone proteins around which DNA is wrapped, and can likely regulate how genes are turned on and off — potentially making it part of a clock oscillator.

When Harmer and colleagues made Arabidopsis plants with a deficient gene, they found that the plants' in-built circadian clock ran fast.

A similar gene is found in humans, and human cells with a deficiency in this gene also have a fast-running clock. When the researchers inserted the plant gene into the defective human cells, they could set the clock back to normal — and the human gene could do the same trick in plant seedlings.

Because the rest of the clock genes are quite different between plants and humans, Harmer thinks that the fact that a very similar gene has the same function in both plants and humans is probably an example of convergent evolution, rather than something handed down from a distant common ancestor.

Convergent evolution is when two organisms arrive at the same solution to a problem but apparently from different starting points.

Maintaining accurate circadian rhythms is hugely important to living things, from maintaining sleep/wake cycles in animals to controlling when plants flower.

The other coauthors on the study are Michael Covington, assistant professor at Rice University; and postdoctoral scholar Luciano DiTacchio, graduate student Christopher Vollmers and Assistant Professor Satchidananda Panda at the Salk Institute. The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.ucdavis.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Trotting robots reveal emergence of animal gait transitions

A four-legged robot trained with machine learning by EPFL researchers has learned to avoid falls by spontaneously switching between walking, trotting, and pronking – a milestone for roboticists as well…

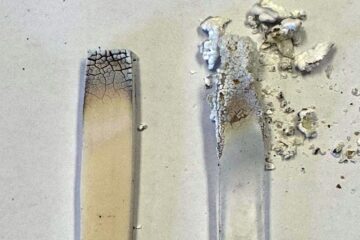

Innovation promises to prevent power pole-top fires

Engineers in Australia have found a new way to make power-pole insulators resistant to fire and electrical sparking, promising to prevent dangerous pole-top fires and reduce blackouts. Pole-top fires pose…

Possible alternative to antibiotics produced by bacteria

Antibacterial substance from staphylococci discovered with new mechanism of action against natural competitors. Many bacteria produce substances to gain an advantage over competitors in their highly competitive natural environment. Researchers…