NASA's CloudSat satellite sees a powerful heat engine in Typhoon Malakas

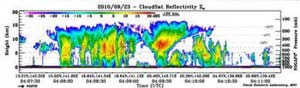

CloudSat captured an image of Typhoon Malakas at12:09 a.m. EDT on Sept. 23 that indicated strong convection on either side of the storm eyewall, with maximum cloud top heights around 9.3 miles (15 kilometers) in the southern quadrant of the storm, and approaching 10 miles (16 km) in the northern quadrant. Credit: NASA/JPL/Colorado State University/Naval Research Laboratory-Monterey<br>

CloudSat flew over Typhoon Malakas during the daytime on Sept. 23. At that time, Malakas had a minimum central pressure of 965 millibars, maximum winds of around 115 mph (100 knots), and a storm width (winds greater than or equal to 57 mph or 50 knots) of around 150 nautical miles.

Dr. Matt Rogers, a research scientist who works on the CloudSat team at the Dept. of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colo. noted that the ” CloudSat overpass of the typhoon occurred around 4:09 GMT (12:09 a.m. EDT/1:09 p.m. local time/Japan), and radar imagery of the typhoon indicated strong convection on either side of the storm eyewall, with maximum cloud top heights around 9.3 miles (15 kilometers) in the southern quadrant of the storm, and approaching 10 miles (16 km) in the northern quadrant.”

A strong convective (rapidly rising air that creates the thunderstorms that power a tropical cyclone) cell dominates the northern quadrant of the storm, while several smaller convective cells combine to make up the southern quadrant, according to the CloudSat overpass.

“The presence of heavy rainfall near the storm core causes radar attenuation – a condition that occurs when the vast amount of water present in the storm scatters or absorbs all available radar energy, leaving no signal to return to the satellite,” Rogers said.

Satellite data also detected an eye 50 nautical miles wide, and around it were the strong thunderstorms wrapping around it and into the storm's center from the southeastern quadrant.

At 1500 UTC (11 a.m. EDT) on Sept. 24, Typhoon Malakas has maximum sustained winds near 103 mph (90 knots). It was located about 75 nautical miles west-northwest of Chi Chi Jima, Japan near 29.8 North and 142.4 East. It was moving north-northeast near 26 mph (23 knots) and kicking up 31-foot high seas.

Malakas has tracked over Iwo To and Chi Chi Jima and is now headed into open waters this weekend. It is forecast to stay at sea and away from land, paralleling the coast of Japan. By Saturday, Malakas is forecast to start transitioning into an extra-tropical storm and weaken gradually. As it continues northeast it will encounter stronger vertical westerly wind shear which will help weaken the system somewhat, but it is forecast to still remain an intense storm after the transition.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.nasa.govAll latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Sea slugs inspire highly stretchable biomedical sensor

USC Viterbi School of Engineering researcher Hangbo Zhao presents findings on highly stretchable and customizable microneedles for application in fields including neuroscience, tissue engineering, and wearable bioelectronics. The revolution in…

Twisting and binding matter waves with photons in a cavity

Precisely measuring the energy states of individual atoms has been a historical challenge for physicists due to atomic recoil. When an atom interacts with a photon, the atom “recoils” in…

Nanotubes, nanoparticles, and antibodies detect tiny amounts of fentanyl

New sensor is six orders of magnitude more sensitive than the next best thing. A research team at Pitt led by Alexander Star, a chemistry professor in the Kenneth P. Dietrich…