Scientists Discover Genetic Basis of Pest Resistance to Biotech Cotton

The findings, reported in the May 19 issue of the journal PLOS ONE, shed light on how the global caterpillar pest called pink bollworm overcomes biotech cotton, which was designed to make an insect-killing bacterial protein called Bt toxin. The results could have major impacts for managing pest resistance to Bt crops.

“Bt crops have had major benefits for society,” said Jeffrey Fabrick, the lead author of the study and a research entomologist at the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Maricopa, Arizona. “By understanding how insects adapt to Bt crops we can devise better strategies to delay the evolution of resistance and extend these benefits.”

“Many mechanisms of resistance to Bt proteins have been proposed and studied in the lab, but this is the first analysis of the molecular genetic basis of severe pest resistance to a Bt crop in the field,” said Bruce Tabashnik, one of the paper's authors and the head of the Department of Entomology in the UA College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. He also is a member of the UA's BIO5 Institute.

Based on laboratory experiments aimed at determining the molecular mechanisms involved, scientists knew that pink bollworm could evolve resistance against the Bt toxin, but they had to go all the way to India to observe this happening in the field.

Farmers in the U.S., but not in India, adopted tactics designed to slow evolution of resistance in pink bollworm. Scientists from the UA and the USDA worked closely with cotton growers in Arizona to develop and implement resistance management strategies such as providing “refuges” of standard cotton plants that do not produce Bt proteins and releasing sterile pink bollworm moths. Planting refuges near Bt crops allows susceptible insects to survive and reproduce and thus reduces the chances that two resistant insects will mate with each other and produce resistant offspring. Similarly, mass release of sterile moths also makes it less likely for two resistant individuals to encounter each other and mate.

As a result, pink bollworm has been all but eradicated in the southwestern U.S. Suppression of this pest with Bt cotton is the cornerstone of an integrated pest management program that has allowed Arizona cotton growers to reduce broad spectrum insecticide use by 80 percent, saving them over $10 million annually.

In India, however, resistant pink bollworm populations have emerged.

Crops genetically engineered to produce proteins from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis – or Bt – were introduced in 1996 and planted on more than 180 million acres worldwide during 2013. Organic growers have used Bt proteins in sprays for decades because they kill certain pests but are not toxic to people and most other organisms. Pest control with Bt proteins – either in sprays or genetically engineered crops – reduces reliance on chemical insecticides. Although Bt proteins provide environmental and economic benefits, these benefits are cut short when pests evolve resistance.

By sequencing the DNA of resistant pink bollworm collected from the field in India – which grows the most Bt cotton of any country in the world – the team found that the insects produce remarkably diverse disrupted variants of a protein called cadherin. Mutations that disrupt cadherin prevent Bt toxin from binding to it, which leaves the insect unscathed by the Bt toxin. The researchers learned that the astonishing diversity of cadherin in pink bollworm from India is caused by alternative splicing, a novel mechanism of resistance that allows a single DNA sequence to code for many variants of a protein.

“Our findings represent the first example of alternative splicing associated with Bt resistance that evolved in the field,” said Fabrick, who is also an adjunct scientist in the Department of Entomology at the UA.

Mario Soberón, a Bt expert at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in Cuernavaca, who was not an author of the study, commented, “This is a neat example of the diverse mechanisms insect possess to evolve resistance. An important implication is that DNA screening would not be efficient for monitoring resistance of pink bollworm to Bt toxins.”

Contacts

Bruce Tabashnik

UA College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

Jeffrey Fabrick

U.S. Department of Agriculture

UANews Contact

Daniel Stolte

520-626-4402

LINKS:

Research paper: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0097900

UA College of Agriculture and Life Sciences: http://ag.arizona.edu

BIO5 Institute: www.bio5.org

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Agricultural and Forestry Science

Newest articles

Microscopic basis of a new form of quantum magnetism

Not all magnets are the same. When we think of magnetism, we often think of magnets that stick to a refrigerator’s door. For these types of magnets, the electronic interactions…

An epigenome editing toolkit to dissect the mechanisms of gene regulation

A study from the Hackett group at EMBL Rome led to the development of a powerful epigenetic editing technology, which unlocks the ability to precisely program chromatin modifications. Understanding how…

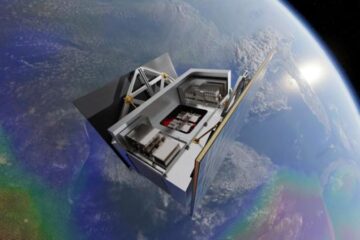

NASA selects UF mission to better track the Earth’s water and ice

NASA has selected a team of University of Florida aerospace engineers to pursue a groundbreaking $12 million mission aimed at improving the way we track changes in Earth’s structures, such…