Ancient popcorn discovered in Peru

Some of the oldest known corn cobs, husks, stalks and tassels, dating from 6,700 to 3,000 years ago were discovered at Paredones and Huaca Prieta, two mound sites on Peru’s arid northern coast. Credit: Tom D. Dillehay<br>

Some of the oldest known corncobs, husks, stalks and tassels, dating from 6,700 to 3,000 years ago were found at Paredones and Huaca Prieta, two mound sites on Peru's arid northern coast. The research group, led by Tom Dillehay from Vanderbilt University and Duccio Bonavia from Peru's Academia Nacional de la Historia, also found corn microfossils: starch grains and phytoliths.

Characteristics of the cobs—the earliest ever discovered in South America—indicate that the sites' ancient inhabitants ate corn several ways, including popcorn and flour corn. However, corn was still not an important part of their diet.

“Corn was first domesticated in Mexico nearly 9,000 years ago from a wild grass called teosinte,” said Piperno. “Our results show that only a few thousand years later corn arrived in South America where its evolution into different varieties that are now common in the Andean region began. This evidence further indicates that in many areas corn arrived before pots did and that early experimentation with corn as a food was not dependent on the presence of pottery.”

Understanding the subtle transformations in the characteristics of cobs and kernels that led to the hundreds of maize races known today, as well as where and when each of them developed, is a challenge. Corncobs and kernels were not well preserved in the humid tropical forests between Central and South America, including Panama—the primary dispersal routes for the crop after it first left Mexico about 8,000 years ago.

“These new and unique races of corn may have developed quickly in South America, where there was no chance that they would continue to be pollinated by wild teosinte,” said Piperno. “Because there is so little data available from other places for this time period, the wealth of morphological information about the cobs and other corn remains at this early date is very important for understanding how corn became the crop we know today.”

The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, headquartered in Panama City, Panama, is a unit of the Smithsonian Institution. The Institute furthers the understanding of tropical nature and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Agricultural and Forestry Science

Newest articles

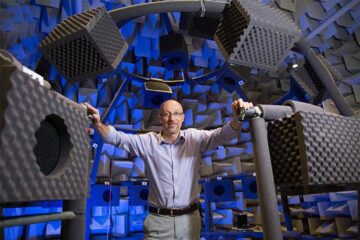

Why getting in touch with our ‘gerbil brain’ could help machines listen better

Macquarie University researchers have debunked a 75-year-old theory about how humans determine where sounds are coming from, and it could unlock the secret to creating a next generation of more…

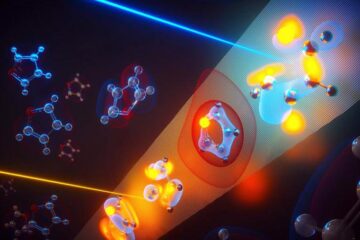

Attosecond core-level spectroscopy reveals real-time molecular dynamics

Chemical reactions are complex mechanisms. Many different dynamical processes are involved, affecting both the electrons and the nucleus of the present atoms. Very often the strongly coupled electron and nuclear…

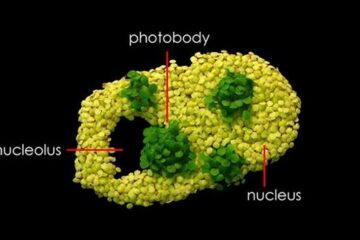

Free-forming organelles help plants adapt to climate change

Scientists uncover how plants “see” shades of light, temperature. Plants’ ability to sense light and temperature, and their ability to adapt to climate change, hinges on free-forming structures in their…