First 3-D processor runs at 1.4 Ghz on new architecture

The next major advance in computer processors will likely be the move from today's two-dimensional chips to three-dimensional circuits, and the first three-dimensional synchronization circuitry is now running at 1.4 gigahertz at the University of Rochester.

Unlike past attempts at 3-D chips, the Rochester chip is not simply a number of regular processors stacked on top of one another. It was designed and built specifically to optimize all key processing functions vertically, through multiple layers of processors, the same way ordinary chips optimize functions horizontally. The design means tasks such as synchronicity, power distribution, and long-distance signaling are all fully functioning in three dimensions for the first time.

“I call it a cube now, because it's not just a chip anymore,” says Eby Friedman, Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Rochester and faculty director of the pro of the processor. “This is the way computing is going to have to be done in the future. When the chips are flush against each other, they can do things you could never do with a regular 2-D chip.”

Friedman, working with engineering student Vasilis Pavlidis, says that many in the integrated circuit industry are talking about the limits of miniaturization, a point at which it will be impossible to pack more chips next to each other and thus limit the capabilities of future processors'. He says a number of integrated circuit designers anticipate someday expanding into the third dimension, stacking transistors on top of each other.

But with vertical expansion will come a host of difficulties, and Friedman says the key is to design a 3-D chip where all the layers interact like a single system. Friedman says getting all three levels of the 3-D chip to act in harmony is like trying to devise a traffic control system for the entire United States—and then layering two more United States above the first and somehow getting every bit of traffic from any point on any level to its destination on any other level—while simultaneously coordinating the traffic of millions of other drivers.

Complicate that by changing the two United States layers to something like China and India where the driving laws and roads are quite different, and the complexity and challenge of designing a single control system to work in any chip begins to become apparent, says Friedman.

Since each layer could be a different processor with a different function, such as converting MP3 files to audio or detecting light for a digital camera, Friedman says that the 3-D chip is essentially an entire circuit board folded up into a tiny package. He says the chips inside something like an iPod could be compacted to a tenth their current size with ten times the speed.

What makes it all possible is the architecture Friedman and his students designed, which uses many of the tricks of regular processors, but also accounts for different impedances that might occur from chip to chip, different operating speeds, and different power requirements. The fabrication of the chip is unique as well. Manufactured at MIT, the chip must have millions of holes drilled into the insulation that separates the layers in order to allow for the myriad vertical connections between transistors in different layers.

“Are we going to hit a point where we can't scale integrated circuits any smaller? Horizontally, yes,” says Friedman. “But we're going to start scaling vertically, and that will never end. At least not in my lifetime. Talk to my grandchildren about that.”

The next major advance in computer processors will likely be the move from today's two-dimensional chips to three-dimensional circuits, and the first three-dimensional synchronization circuitry is now running at 1.4 gigahertz at the University of Rochester.

Unlike past attempts at 3-D chips, the Rochester chip is not simply a number of regular processors stacked on top of one another. It was designed and built specifically to optimize all key processing functions vertically, through multiple layers of processors, the same way ordinary chips optimize functions horizontally. The design means tasks such as synchronicity, power distribution, and long-distance signaling are all fully functioning in three dimensions for the first time.

“I call it a cube now, because it's not just a chip anymore,” says Eby Friedman, Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Rochester and faculty director of the pro of the processor. “This is the way computing is going to have to be done in the future. When the chips are flush against each other, they can do things you could never do with a regular 2-D chip.”

Friedman, working with engineering student Vasilis Pavlidis, says that many in the integrated circuit industry are talking about the limits of miniaturization, a point at which it will be impossible to pack more chips next to each other and thus limit the capabilities of future processors'. He says a number of integrated circuit designers anticipate someday expanding into the third dimension, stacking transistors on top of each other.

But with vertical expansion will come a host of difficulties, and Friedman says the key is to design a 3-D chip where all the layers interact like a single system. Friedman says getting all three levels of the 3-D chip to act in harmony is like trying to devise a traffic control system for the entire United States—and then layering two more United States above the first and somehow getting every bit of traffic from any point on any level to its destination on any other level—while simultaneously coordinating the traffic of millions of other drivers.

Complicate that by changing the two United States layers to something like China and India where the driving laws and roads are quite different, and the complexity and challenge of designing a single control system to work in any chip begins to become apparent, says Friedman.

Since each layer could be a different processor with a different function, such as converting MP3 files to audio or detecting light for a digital camera, Friedman says that the 3-D chip is essentially an entire circuit board folded up into a tiny package. He says the chips inside something like an iPod could be compacted to a tenth their current size with ten times the speed.

What makes it all possible is the architecture Friedman and his students designed, which uses many of the tricks of regular processors, but also accounts for different impedances that might occur from chip to chip, different operating speeds, and different power requirements. The fabrication of the chip is unique as well. Manufactured at MIT, the chip must have millions of holes drilled into the insulation that separates the layers in order to allow for the myriad vertical connections between transistors in different layers.

“Are we going to hit a point where we can't scale integrated circuits any smaller? Horizontally, yes,” says Friedman. “But we're going to start scaling vertically, and that will never end. At least not in my lifetime. Talk to my grandchildren about that.”

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.rochester.eduAll latest news from the category: Information Technology

Here you can find a summary of innovations in the fields of information and data processing and up-to-date developments on IT equipment and hardware.

This area covers topics such as IT services, IT architectures, IT management and telecommunications.

Newest articles

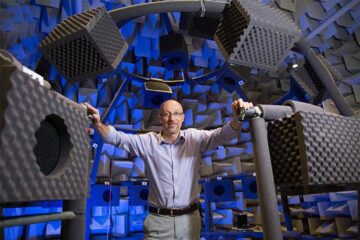

Why getting in touch with our ‘gerbil brain’ could help machines listen better

Macquarie University researchers have debunked a 75-year-old theory about how humans determine where sounds are coming from, and it could unlock the secret to creating a next generation of more…

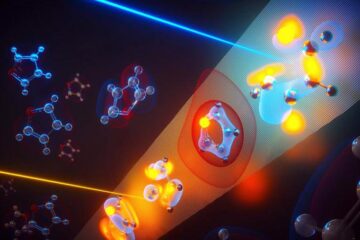

Attosecond core-level spectroscopy reveals real-time molecular dynamics

Chemical reactions are complex mechanisms. Many different dynamical processes are involved, affecting both the electrons and the nucleus of the present atoms. Very often the strongly coupled electron and nuclear…

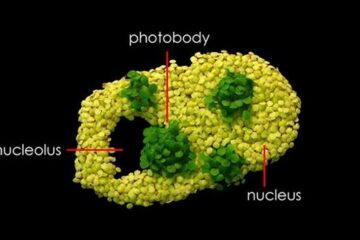

Free-forming organelles help plants adapt to climate change

Scientists uncover how plants “see” shades of light, temperature. Plants’ ability to sense light and temperature, and their ability to adapt to climate change, hinges on free-forming structures in their…