AI Generated Image

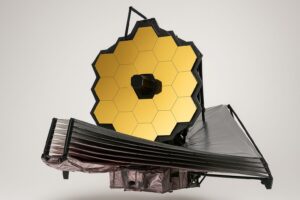

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Tiny crimson specks discovered by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) could represent an entirely new class of cosmic object — massive black holes wrapped in star-like atmospheres — offering fresh insights into how the first galaxies may have formed.

Unexpected Red Dots Challenge Existing Theories

When JWST began sending data in 2022, astronomers were startled by the presence of tiny “little red dots” scattered across the early universe. Initially, researchers, including a team from Penn State, proposed that these objects might be ancient galaxies—fully developed just 500 to 700 million years after the Big Bang, despite being as mature as the present-day Milky Way, which is about 13.6 billion years old.

Because such fully formed galaxies at that early epoch would defy existing models of cosmic evolution, the researchers nicknamed these objects “universe breakers.”

New Study Points to ‘Black Hole Stars’

In a new study published on Sept. 12 in Astronomy & Astrophysics, an international collaboration of astronomers and physicists, including Penn State scientists, offers a radically different interpretation. They suggest these red dots might not be galaxies at all, but rather “black hole stars” — giant spheres of gas powered by supermassive black holes at their centers.

According to the team, these objects emit light like stars but are fueled not by nuclear fusion, but by the rapid consumption of surrounding matter by central black holes. The inflowing matter converts to energy, producing an intense glow.

“Basically, we looked at enough red dots until we saw one that had so much atmosphere that it couldn’t be explained as typical stars we’d expect from a galaxy,” said Joel Leja, the Dr. Keiko Miwa Ross Mid-Career Associate Professor of Astrophysics at Penn State and co-author of the study. “It’s an elegant answer really, because we thought it was a tiny galaxy full of many separate cold stars, but it’s actually, effectively, one gigantic, very cold star.”

A Curious Mix of Cold Light and Black Holes

Cold stars emit very little visible light, glowing mainly in red or near-infrared wavelengths. While gas near black holes is usually extremely hot—millions of degrees Celsius—the emission from these mysterious dots appears dominated by cold gas. This unusual signature resembles that of low-mass, cold stars, not typical galactic structures.

JWST, the most powerful space telescope ever built, can detect light from the universe’s earliest stars and galaxies. Leja noted that the telescope essentially allows scientists to see back about 13.5 billion years. Soon after it launched, researchers around the world began spotting these unexpectedly massive red dots, which appeared far denser than existing galaxy models could explain.

“The night sky of such a galaxy would be dazzlingly bright,” said Bingjie Wang, now a NASA Hubble Fellow at Princeton University who worked on the study as a postdoctoral researcher at Penn State. “If this interpretation holds, it implies that stars formed through extraordinary processes that have never been observed before.”

Tracking Down ‘The Cliff’

To unlock the mystery, the team spent nearly 60 hours of JWST observing time between January and December 2024 collecting spectra—data showing how much light objects emit at different wavelengths—from about 4,500 distant galaxies. This created one of the largest JWST spectroscopic datasets to date.

In July 2024, they identified a particularly extreme object, nicknamed “The Cliff,” whose spectrum indicated enormous mass. Its light took 11.9 billion years to reach Earth, and analysis revealed it was likely a supermassive black hole enveloped in a massive shell of hydrogen gas.

“The extreme properties of The Cliff forced us to go back to the drawing board, and come up with entirely new models,” said Anna de Graaff, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy and the paper’s corresponding author, in a Max Planck Institute press release.

Clues to the Birth of Supermassive Black Holes

Leja explained that black holes reside at the centers of most galaxies and can be millions or billions of times the mass of the Sun. How they formed has long puzzled scientists.

“No one’s ever really known why or where these gigantic black holes at the center of galaxies come from,” Leja said. “These black hole stars might be the first phase of formation for the black holes that we see in galaxies today — supermassive black holes in their little infancy stage.”

Leja added that JWST has already found hints of high-mass black holes in the early universe. These “black hole star” objects—if confirmed—could fill a key gap in models of how cosmic structures emerged so quickly after the Big Bang. The team plans further studies to measure their density and energy output.

Looking Ahead: A New Cosmic Puzzle

Despite the breakthrough, the red dots remain distant, tiny, and difficult to study in detail.

“This is the best idea we have and really the first one that fits nearly all of the data, so now we need to flesh it out more,” Leja said. “It’s okay to be wrong. The universe is much weirder than we can imagine and all we can do is follow its clues. There are still big surprises out there for us.”

Summary: Key Points

- JWST discovered mysterious “little red dots” in the early universe.

- Initially thought to be ancient, fully formed galaxies, they defy current galaxy formation models.

- New research suggests they are “black hole stars” — giant gas spheres powered by supermassive black holes.

- One extreme object, “The Cliff,” helped confirm this theory using spectral data.

- These objects could represent the earliest stages of supermassive black hole formation.

- Further studies will explore their gas density and energy output to test this hypothesis.

Original Publication

Authors: Anna de Graaff, Hans-Walter Rix, Rohan P. Naidu, Ivo Labbé, Bingjie Wang, Joel Leja, Jorryt Matthee, Harley Katz, Jenny E. Greene, Raphael E. Hviding, Josephine Baggen, Rachel Bezanson, Leindert A. Boogaard, Gabriel Brammer, Pratika Dayal, Pieter van Dokkum, Andy D. Goulding, Michaela Hirschmann, Michael V. Maseda, Ian McConachie, Tim B. Miller, Erica Nelson, Pascal A. Oesch, David J. Setton, Irene Shivaei, Andrea Weibel, Katherine E. Whitaker and Christina C. Williams.

Journal: Astronomy and Astrophysics

DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202554681

Method of Research: Imaging analysis

Subject of Research: Not applicable

Article Title: A remarkable ruby: Absorption in dense gas, rather than evolved stars, drives the extreme Balmer break of a little red dot at z = 3.5

Article Publication Date: 12-Sep-2025

Original Source: https://www.psu.edu/news/research/story/mysterious-red-dots-early-universe-may-be-black-hole-star-atmospheres

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main finding about the source known as The Cliff?

The Cliff is not powered by a dense population of evolved stars, as previously thought, but rather by a central ionizing source, likely a black hole, surrounded by dense gas.

How does the Balmer break in The Cliff compare to other high-redshift galaxies?

The Balmer break in The Cliff is exceptionally strong, more than twice as strong as any previously observed in high-redshift galaxies, indicating a unique spectral characteristic.

What implications does the study of The Cliff have for our understanding of galaxy formation?

The findings suggest that some compact, high-redshift sources previously thought to be ultra-dense galaxies may actually be powered by active galactic nuclei, challenging existing models of galaxy formation and evolution.