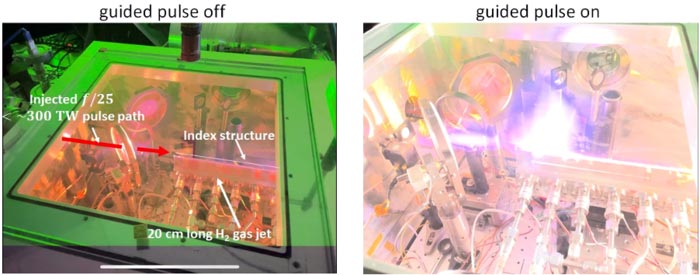

Photos of target chamber without and with injection and guiding of ultra-intense laser pulse into 20 cm long waveguide. Laser guiding leads to multi-GeV electron acceleration, with an intense burst of electrons emerging at the exit of the plasma waveguide (to the right).

Credit: University of Maryland

Experiments drive electrons to multi-GeV energies in an all-optical laser-driven accelerator.

Charged particle accelerators have been a central tool of basic physics research for almost a hundred years, perhaps most famously as “atom smashers” for understanding the elementary constituents of the universe. As accelerators have progressed to ever higher energies to probe ever smaller constituents, they have grown to enormous size: the Large Hadron Collider is a remarkable 27 kilometers in circumference.

Recently, however, researchers at the University of Maryland have used intense lasers and plasmas to make a significant advance in shrinking the size of accelerators.

The advent of intense ultrashort pulse lasers in the 1980s and 90s (subject of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics) has led to electromagnetic (EM) fields hundreds of thousands of times stronger than used to accelerate charged particles in state-of-the-art conventional accelerators. If not for structure damage by ultra-strong EM fields, laser-driven accelerators could be hundreds of thousands times shorter. This is where plasmas come to the rescue, as realized by Tajima and Dawson in 1979, pioneering the field of plasma-based acceleration. Plasmas are indestructible (they are already, in some sense, destroyed!), and they add their own huge fields to accelerate electrons. But conventional accelerators have a long metal tube, a “waveguide,” to keep the EM wave confined and strong to maintain the acceleration process. How can that be replaced for ultra-intense lasers?

The Maryland researchers demonstrated a functional equivalent of a confining metal tube waveguide in the form of a plasma waveguide generated in hydrogen gas by one or two additional laser pulses. In contrast to the metal tubes that are a few centimeters wide, the free-standing laser-generated plasma waveguide can confine an injected ultra-intense laser pulse to a width thinner than a human hair and maintain it over meter-scale distances (Figure 1). Although the plasma lasts only a few nanoseconds before it expands and recombines, this is good enough for the accelerator pulses, which move at nearly the speed of light.

In collaboration with Colorado State University, the Maryland group demonstrated plasma waveguiding of up to 300-terawatt laser pulses from the Aleph laser (the peak total U.S. power usage is less than 2 terawatts), and acceleration of electrons up to 5 GeV over a distance of only 20 cm. This gives an acceleration per meter of length that is thousands of times larger than conventional accelerators. This huge acceleration gradient is generated by the plasma’s response to the intense pulse propagating down the waveguide; this “plasma wave” response can trap and accelerate bunches of electrons that “surf” on the wave. The goal of these experiments—funded by the Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation—is demonstration of a 10 GeV laser-driven acceleration stage, with the idea that multiple stages can contribute to a future linear collider for high energy physics.

One important new advance in these results is that the plasma density was kept very low while still maintaining efficient waveguide confinement of the pulse (it is much easier to make high density plasma waveguides). This ensures that the speed of the intense pulse in the waveguide is always very close to the speed of light in a vacuum. Remarkably, at higher plasma density, accelerated electrons can catch up to and outrun the laser pulse, decelerating in the process!

In addition to fundamental physics studies, accelerators are also used extensively for applications such as medical isotope production and medical therapy. In addition, because charged particles accelerate, they also emit beams of photons that are used in yet more applications.

Abstracts

BO04.00006 GeV Electron Acceleration by Self-waveguiding Pulses

Session

BO04: Laser-Plasma Wakefield and Direct Laser Accelerators

9:30 AM–12:30 PM, Monday, November 8, 2021

Room: Rooms 304-305

CI01.00001 Meter-scale plasma waveguides for laser wakefield acceleration

Session

CI01: Plasma Accelerators and Beams

2:00 PM–5:30 PM, Monday, November 8, 2021

Room: Ballroom B