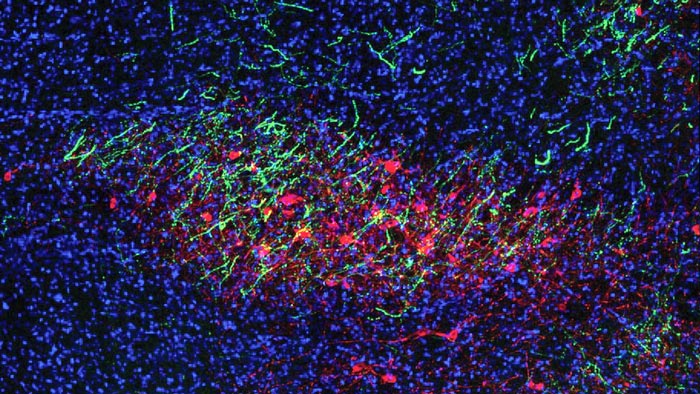

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Professor Bo Li discovered a cluster of neurons in the mouse brain that influence motivation. These cells activate a gene called Fezf2 and are connected to and activate other neurons, which are stained green in this image of a mouse brain.

Credit: Li lab/CSHL, 2021

A characteristic of depression is a lack of motivation. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor Bo Li, in collaboration with CSHL Adjunct Professor Z. Josh Huang, discovered a group of neurons in the mouse brain that influences the animal’s motivation to perform tasks for rewards. Dialing up the activity of these neurons makes a mouse work faster or more vigorously—up to a point. These neurons have a feature that prevents the mouse from becoming addicted to the reward. The findings may point to new therapeutic strategies for treating mental illnesses like depression that affect motivation in humans.

The anterior insular cortex is a region of the brain that plays a critical role in motivation. A set of neurons that activate a gene called Fezf2(Fezf2 neurons) in this area are active when mice are doing both physical and cognitive tasks. Li and his lab hypothesized that these neurons do not affect the mouse’s ability to do the task; rather, the brain cells influence the mouse’s motivational drive.

Mice were trained to lick a water bottle spout to receive a small sugar reward. When researchers dialed up the activity of these Fezf2 neurons, mice would lick more vigorously. If the neuron activity was dialed down, the mice would lick more slowly. The researchers saw a similar result in another experiment in which the mice ran on a wheel to receive a reward. The mice ran faster if the Fezf2 neurons were stimulated. The same effect occurred with other tasks.

Li and his team were surprised to discover a feature that prevents the mice from becoming addicted to the tasks and their rewards. When mice drank their fill of sugar water and were satiated, they would not lick or run faster to get more sugar, even if the researchers dialed up the activity of the Fezf2 neurons.

Finding a way to fine-tune the human equivalent of these neurons might help people struggling with motivation due to mental illnesses like depression. Li says, “We want to selectively increase the motivation of the person so that they can do the things that they need to do, but we don’t want to create addictive drugs.”

Li and Huang published their findings in the journal Cell.

Journal: Cell

DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.11.019

Article Title: A genetically defined insula-brainstem circuit for selective control of motivational vigor

Article Publication Date: 9-Dec-2021

Media Contact

Sara Roncero-Menendez

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

roncero@cshl.edu

Office: 516-367-6866