Working the switches for axon branching

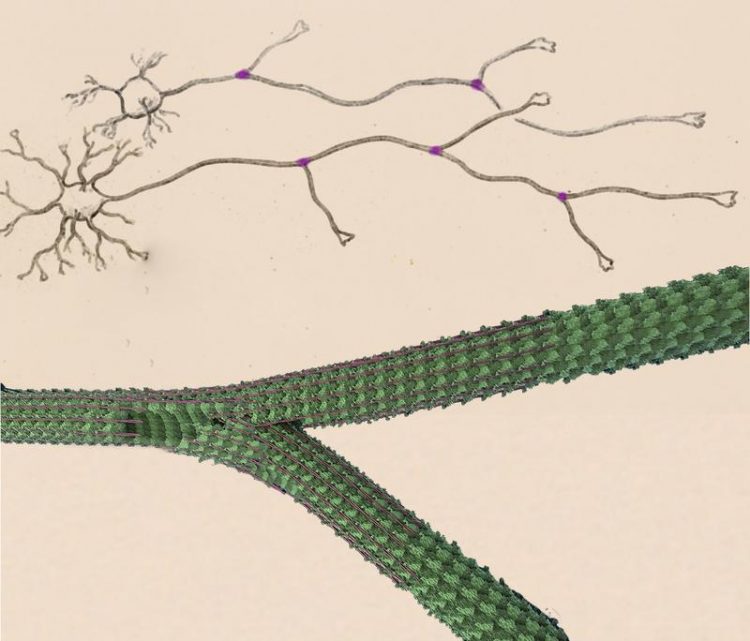

In neuronal cells, the protein SSNA1 (pink) accumulates at branching sites in axons (top). The SSNA1 fibrils attach to the microtubules (green) and trigger branching (bottom). © Naoko Mizuno, MPI of Biochemistry

From the twigs of trees to railroad switches – our environment teems with rigid branched objects. These objects are so omnipresent in our lives, we barely notice them anymore. The branching can be achieved by different strategies. While railroad switches use special construction components, twigs grow from dormant buds in existent branches. However, not all biological branchings are so well understood.

How to branch an axon

Neuronal cells in the brain form complex networks in order to process information. These cells consist of a cell body with dendrites that collect incoming information and a single long axon that transmits information to other cells. Researchers from the group “Cellular and Membrane Trafficking” of Naoko Mizuno at the MPIB have studied the processes involved in branching of axons. The shape of the axon is stabilized by an internal support system of hollow tubes – the microtubules.

The microtubules are well-studied components of the cytoskeleton because they are involved in processes ranging from cell division and cell shape to intracellular transport. Hence, they combine diverse functions like intracellular railroad tracks with steel beams that maintain the architecture.

Microtubules are built in a directed manner from small tubulin protein building blocks that attach to the growing end of the microtubule. Tubulins align in parallel to each other and form a hollow tube. This hollow space gives rigidity to the microtubules.

“Researchers have not been able to observe branching of the microtubules”, says Nirakar Basnet, PhD student in Naoko Mizuno’s group and the first author of the study. “We show that a protein called SSNA1 accumulates at the sites where axons form branching points”, explains Basnet.

Let’s branch – but not too much

This observation cued the researchers to further study SSNA1. They found that the protein also forms filaments, albeit much thinner than the microtubules. These filaments attach to the surface of the growing microtubule and curve it outwards. The curvature forces branching of the growing microtubules.

It is a completely new principle of microtubule dynamics that the branching is inserted at the time of formation. Additionally, SSNA1 can cause branchings by connecting the ends of existing microtubules and by adding a new branch to an existing tubule, similar to the twig of a tree.

SSNA1 is indispensable for the neuronal development. Without SSNA1, the microtubules only form long unbranched tubes and consequentially the axons are also not branched. However, axon branching must be carefully regulated. When the researchers increased the concentration of the SSNA1 in cells, the microtubules increased in number but became shorter. “The local concentration of SSNA1 must be quite high to trigger branching”, states Basnet, “This could be a safety mechanism to prevent too much branching”.

Guiding the way for axon branching

Naoko Mizuno, group leader at the MPIB, describes SSNA1 as a “guide-rail” for the new branches of the microtubule. “The proteins form filaments that lead the way for the newly forming microtubule. In a way, SSNA1 is a railroad switch that leads to the branching of the track. But, unlike a railroad switch, it is not part of the track itself but rather marks the branching point from outside the track.” A railroad switch increases the number of destinations the train can reach. Similarly, the branched axons can make connections to a higher number of other neuronal cells.

Mizuno, explains that the current study was rendered possible by combining a range of microscopy technologies. “For example, we used cryoEM to study how SSNA1 attaches to the microtubules. With DNA-PAINT – a super-resolution light microscopy technology that was also developed at the MPIB – we could observe individual microtubules in the complex networks within the cells.” The synergy effect of combining different expertises from the Institute and from external partners contributed to the study which proposes a new concept in microtubule biology. “Many questions regarding cytoskeleton functions in other processes are still unanswered”, says Mizuno and speculates that the new branching mechanism could have implications in functions beyond axon branching. [CW]

About Naoko Mizuno

Naoko Mizuno studied biophysics at the University of Tokyo in Japan. In 2005, she received her PhD from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in the USA. After her postdoctoral work, she became a research fellow at the the Laboratory of Structural Biology at the National Institutes of Health in the USA. Since 2013, Mizuno has been a group leader at the MPIB. She has received various awards and research grants, among them the EMBO Young Investigators award and an ERC consolidator grant.

About the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry

The Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry (MPIB) belongs to the Max Planck Society, an independent, non-profit research organization dedicated to top-level basic research. As one of the largest Institutes of the Max Planck Society, about 800 employees from 45 nations work here in the field of life sciences. In currently about 35 departments and research groups, the scientists contribute to the newest findings in the areas of biochemistry, cell biology, structural biology, biophysics and molecular science. The MPIB in Munich-Martinsried is part of the local life-science-campus in close proximity to the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology, a Helmholtz Center, the Gene-Center, several bio-medical faculties of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München and the Innovation and Founding Center Biotechnology (IZB). http://biochem.mpg.de

Naoko Mizuno, PhD

Cellular and Membrane Trafficking

Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry

Am Klopferspitz 18

82152 Martinsried/Munich

Germany

E-mail: mizuno@biochem.mpg.de

http://www.biochem.mpg.de/en/rg/mizuno

N. Basnet, H. Nedozralova, A. Crevenna, S. Bodakuntla, T. Schlichthaerle, M. Taschner, G. Cardone, C. Janke, R. Jungmann, M. Magiera, C. Biertümpfel, N. Mizuno: Microtubule nucleation factor SSNA1 induces direct branched microtubules; its implications in axon branching. Nature Cell Biology, September 2018

DOI: 10.1038/s41556-018-0199-8

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Security vulnerability in browser interface

… allows computer access via graphics card. Researchers at Graz University of Technology were successful with three different side-channel attacks on graphics cards via the WebGPU browser interface. The attacks…

A closer look at mechanochemistry

Ferdi Schüth and his team at the Max Planck Institut für Kohlenforschung in Mülheim/Germany have been studying the phenomena of mechanochemistry for several years. But what actually happens at the…

Severe Vulnerabilities Discovered in Software to Protect Internet Routing

A research team from the National Research Center for Applied Cybersecurity ATHENE led by Prof. Dr. Haya Schulmann has uncovered 18 vulnerabilities in crucial software components of Resource Public Key…