As aesthetically pleasing as the ocean looks, it contributes far more toward the stability and continuity of life forms than one could guess. Since it covers 70 percent of the planet’s surface, it plays an essential role in the functioning of the climate and weather. The water vapor from the ocean helps to form all kinds of precipitation, such as rain. Additionally, the ocean’s heat is transferred to the atmosphere, which helps distribute warmth around the globe.

Although oceans have a natural process of self-cleaning, studies have shown that man-caused pollution, toxic vegetation, and harmful practices threaten their existence. Algae grow in water bodies such as the oceans, rivers, and lakes. A few of them produce toxins that are damaging to the aquatic environment. One such toxic algae, known as Karenia mikimotoi algae, otherwise called an algal bloom, has been killing marine species and threatening aquatic life.

Coastal Agriculture Linked to Harmful Algal Blooms in the Gulf of California, Stanford Study Reveals

Scientists have found the first direct evidence linking large-scale coastal farming to massive blooms of marine algae that are potentially harmful to ocean life and fisheries.

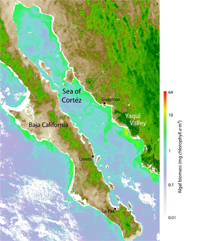

Researchers from Stanford University’s School of Earth Sciences made the discovery by analyzing satellite images of Mexico’s Sea of Cortez, also known as the Gulf of California-a narrow, 700-mile-long stretch of the Pacific Ocean that separates the Mexican mainland from the Baja California Peninsula. Immortalized in the 1941 book Sea of Cortez, by writer John Steinbeck and marine biologist Edward Ricketts, the region remains a hotspot of marine biodiversity and one of Mexico’s most important commercial fishing centers.

The results of the Stanford study will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in San Francisco on Dec. 13.

Algal blooms

Algal blooms occur naturally when cold-water upwellings bring from the seafloor to the surface nutrients that stimulate the rapid reproduction and growth of microscopic algae, also known as phytoplankton. These events often benefit marine ecosystems by generating tons of algae that are consumed by larger organisms.

But several phytoplankton species produce harmful blooms, known as red or brown tides, which release toxins in the water that can poison mollusks and fish. Excessively large blooms can also overwhelm a marine ecosystem by creating oxygen-depleted “dead zones” in the ocean. Scientists have long suspected that many harmful blooms are fueled by fertilizer runoff from farming operations, which in many regions pour tons of excess nitrogen and other nutrients into rivers that eventually flow into coastal waters. However, some agricultural industry groups contend that there is not enough evidence to link farm runoff to red tides or dead zones.

Satellite imagery

To assess the impact of agriculture on marine algae, Stanford scientists turned their attention to one of Mexico’s most productive coastal farming regions-the Yaqui River Valley, which drains into the Sea of Cortez.

“The Yaqui Valley agricultural area is 556,000 acres [225,000 hectares] of irrigated wheat,” said Pamela A. Matson, the dean of Stanford’s School of Earth Sciences and co-author of the AGU study. “The entire valley is irrigated and fertilized in very short windows of time during a six-month cycle. The excess water from irrigation runs off through streams and channels into the estuaries, and then out to sea.”

Matson and her colleagues wondered if each fertilization and irrigation event would trigger a noticeable phytoplankton bloom near the mouth of the Yaqui River, which is located on the mainland side of the Sea of Cortez. To find out, the researchers analyzed a series of images from an orbiting NASA satellite called SeaWiFS, which is equipped with special light-sensitive instruments that can detect phytoplankton floating near the surface of the sea. “These instruments measure the level of greenness in the water,” explained Kevin R. Arrigo, an associate professor of geophysics at Stanford and co-author of the AGU paper. “The greener the water, the more phytoplankton there are.”

Dramatic results

Stanford doctoral candidate Mike Beman carefully analyzed dozens of SeaWiFS images taken over the Sea of Cortez from 1998 through 2002. The results were dramatic. “I looked at five years of satellite data,” said Beman, lead author of the study. “There were roughly four irrigation events per year, and right after each one, you’d see a bloom appear within a matter of days.”

Each bloom was enormous, he said, covering from 19 to 223 square miles (50 to 577 square kilometers) of the Sea of Cortez and lasting several days. “Sometimes eddies actually pulled the plumes across the gulf, from the mainland side all the way to the Baja Peninsula,” Beman added. “Mike found that immediately following each one-week window in which much of the valley was irrigated, there was a response in the ocean off the coast of the Yaqui Valley,” Matson explained.

“We were quite surprised,” Arrigo added, noting that the AGU paper marks the first time that scientists have documented a “one-to-one correspondence between an irrigation event and a massive algal bloom.”

Red tides and dead zones

According to the researchers, artificially induced algal blooms could have major impacts on recreational and commercial fishing, major industries in the Sea of Cortez. Red tides, for example, can cause outbreaks of life-threatening diseases, such as paralytic shellfish poisoning, which can shut down mussel and clam harvesting for long periods of time.

Another concern is hypoxia, or oxygen depletion, which is caused by excessive algae growth. As the algal mass sinks, it is consumed by bacteria, which use up most of the oxygen in the water as they multiply. The result is an oxygen-depleted dead zone at the bottom of the sea where few creatures can survive. A massive dead zone appears every summer in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Louisiana and Texas. Scientists believe that agricultural runoff from the Mississippi River plays a pivotal role in creating this annual dead zone, which measured 8,500 square miles (22,000 square kilometers) in 2002-an area bigger than the state of Massachusetts.

“In the Sea of Cortez, there’s the possibility that hypoxia could occur at a local scale, which could be devastating to the shrimp and shellfish industries,” Matson said. “Shrimp fisheries are very important economically, and they’re already under a lot of stress from overfishing and aquaculture. It is possible that agricultural runoff could cause additional stress if it does lead to toxic blooms or hypoxia.” She and her colleagues plan to conduct follow-up studies to assess the ecological impact of Yaqui Valley runoff events.

“The availability of high-resolution satellite data has opened up a whole new opportunity to look at the importance of what’s going on on land in the sea,” Matson added. “This study shows that you have to pay attention to the land-sea connections.”

Which Place Is Reported to Have the Highest Algal Blooms?

Many decades ago, a few countries were reported to have an outburst of harmful algal blooms (HABs). However, over the years, most of the coastal countries are now threatened with HABs, especially in the heavily populated ones. What’s distressing is that the algal blooms have mutated into more than one toxic species, increasing incident reports and spread geographically.

Human-induced factors, such as climatic pattern shifts and pollution, along with natural dispersions of algal blooms, have impacted marine resources and also resulted in higher economic losses.

Measures Taken to Control Algal Blooms

Ecosystems are far more fragile than scientists can infer. Hence, it is crucial to carry out measures that safeguard the environment. Research is being conducted that focuses on technologies and methods that control or limit algal bloom growth and/or physically eradicate toxins and cells from water bodies. The following 4 methods provide hope to curb the growth and expansion of these marine life threats:

- Biological Control: This refers to the use of one living organism to control the other. One such proposed biological control is the release of Amoebophyra, which is a syndinian parasite. However, ethical debates and the lack of efficacy-related studies have resulted in this control being conceptualized.

- Chemical Control: Copper sulfate was attempted through crop-dusting airplanes. Although effective in reducing the bloom size, it was discontinued due to the negative impacts on marine life forms. Recently, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was used to control algal blooms, but further research was needed to ensure that optimal usage was safe for ocean wildlife.

- Physical/Mechanical Control: Old processes such as flocculation, whereby types of clay are applied during blooms, which help in purifying oceanic waters. Both South Korea and China have employed this control for algal blooms. Additionally, a new project in the US is exploring the role of clay mitigation to control the West Coast of Florida’s red tides.

- Environmental Control: This control involves changing the physical or chemical components of the environment through pollution-control policies in coastal water bodies, dredging, and aeration. The goal is to either kill/control the target species or introduce an enhanced biological control for the target species.

A Blooming Threat—Efforts on Safeguarding Oceans

As research underscores the link between coastal agriculture and harmful algal blooms, it becomes clear that the health of our oceans is deeply tied to human activity on land. Recognizing the fragile interdependence between land and sea is the first step toward framing sustainable solutions that protect aquatic life and preserve the ocean’s key role in our planet’s ecosystem balance.