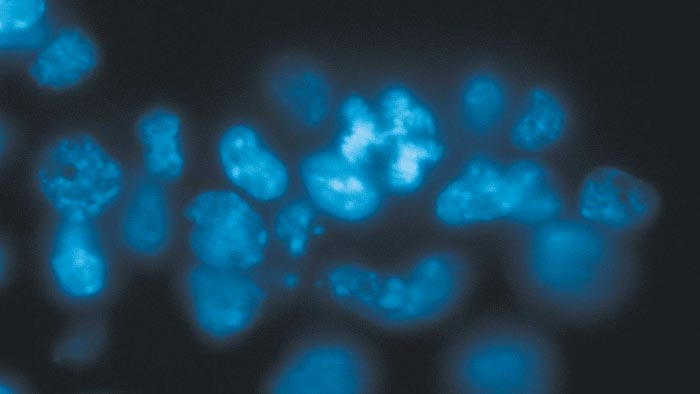

A mouse cell is dividing abnormally in the center of this image. Instead of dividing its chromosomes equally into two cells, the cell is dividing into three cells. Chromosomes are stained in blue. These cells have a mutation in the gene dicer, which makes a protein that stabilizes chromosomes. Dicer makes sure the chromosomes divide and segregate evenly during cell division.

Credit: Michael Gutbrod/Martienssen lab/CSHL, 2022

Cells use RNA as a versatile tool to regulate the activity of their genes. Small snippets of RNA can fine-tune how much protein is produced from various genes; some small RNAs can shut genes off altogether. An enzyme called Dicer chops RNA into smaller pieces: plants use it to chew up the RNA of invading viruses; worms use it to shut genes off during development; and humans use it to produce gene-regulating microRNAs. Dicer is also of interest because mutations in the gene for the enzyme appear to contribute to some human cancers, although it hasn’t been clear exactly why.

In a new study published February 22, 2022 in the journal Nature Communications, researchers led by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Professor Rob Martienssen found an unexpected role for Dicer in mammalian cells: they’ve discovered that the enzyme is important for maintaining the structural integrity of the genome.

When Martienssen’s team removed Dicer from the embryonic stem cells of mice, the cells became sick. Chromosomes inside dividing cells couldn’t properly align themselves for equal distribution to daughter cells. Cell division slowed, and many cells died. Martiennsen’s team had seen this before when they removed Dicer from yeast cells. And when they explored further, they found that Dicer stabilizes the mouse genome in much the same way it maintains the genome in yeast, suggesting that this is an evolutionarily ancient role for the enzyme.

“The new function that we have identified for Dicer genome stability, independently of other well-known small RNA pathways could be an explanation of why Dicer mutations are an important factor in certain types of cancer,” says Benjamin Roche, a researcher in Martienssen’s lab.

Normally, Dicer works with a gene-activating protein called BRD4. The research team found that when Dicer was broken and BRD4 was intact, chromosomes were unstable. Removing a small piece of BRD4 (called bromodomain 2) restored chromosome stability. Like Dicer, BRD4 is often mutated in human cancers. Martienssen says, “Our findings suggest that inhibitors that target BRD4 bromodomain 2 might have specific therapeutic effects when Dicer is compromised in cancer.” The work suggests a new diagnostic and treatment strategy for cancers with compromised Dicer systems using BRD4-targeted drugs.

Journal: Nature Communications

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-04010-3

Article Title: Dicer promotes genome stability via the bromodomain transcriptional co-activator BRD4

Article Publication Date: 22-Feb-2022

Media Contact

Sara Roncero-Menendez

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

roncero@cshl.edu

Office: 516-367-6866