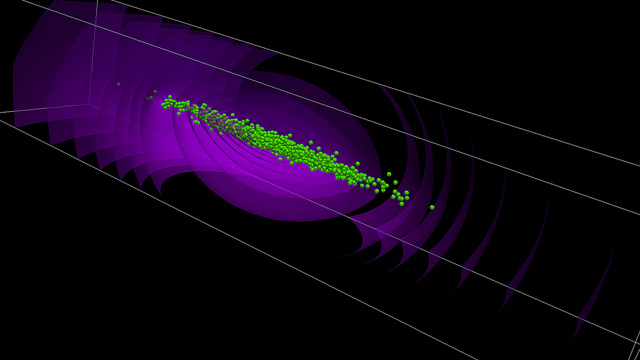

Credit: James Amundson, Fermilab

Synergia simulation of a bunched beam including particles (green) and self-fields (purple).

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, the world’s most powerful accelerator, applied greater energy to a similar scenario on July 4, 2012, to detect the Higgs boson, the particle that gives mass and meaning to the top quark and all other fundamental particles associated with physics’ Standard Model.

Particle physics is a continual search for the ever more elusive subatomic particles that bind the fabric of the universe. But to continue to effectively evolve this search, researchers must constantly improve their understanding of the physics occurring within particle accelerators, to consider all of the elements that interact to create successful collisions.

Leading a team from Fermilab, physicist James Amundson is working with the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility (ALCF, a DOE Office of Science User Facility), to perform the complex accelerator simulations aimed at reducing the risks and costs involved in developing the world’s highest intensity particle beams.

ALCF assisted in porting and optimizing Synergia, a state-of-the-art accelerator simulation software package developed by a team at Fermilab. Running across some 100,000 cores on Mira, the hybrid Python code allowed for the development of detailed numerical models that simulate internal accelerator interactions with unprecedented reliability. The results will enable future investigations into the subatomic world at both Fermilab and CERN.

Despite the fact that there are trillions of particles whizzing around Fermilab’s and LHC’s main injectors at any given time, their effect on each is other is relatively small. What affects the particles most are the accelerator’s components, like the huge superconducting magnets and radio frequency cavities that help direct and drive the beams.

“The more particles you have, the more intensity you have, the more pronounced the effects become,” says Amundson. “So, since we want to move toward higher intensities, it’s important for us to understand these intensity-dependent effects which, of course, are the things that are computationally difficult to do.”

High-energy physics is a game of statistics; the more collisions you can trigger, the better the chances of finding what you’re looking for. But slight disturbances in a beam’s single-minded mission can cause particles to stray, thus reducing the chances of a higher outcome.

In this case, the culprits charged with leading particles off the straight and narrow are effects called wakefields and space charge, which are present for all particles. Because the effects die away at high energy and low intensity, they are only important in high-intensity, low-energy machines.

Similar to the like poles of two magnets, space charge asserts that since all particles in a particular accelerator experiment have the same charge, they tend to push each other away. Wakefields are the way in which beam particles affect other beam particles.

“In a wakefield, the passing of one charged particle through a conducting pipe generates a current in the pipe, producing a field that affects the other particles. An analogy would be a boat leaving a wake that is felt by other boats nearby,” explains Amundson.

As intensity increases—the number or amount of beams and particles—these effects change the dynamics of the beam and raises concerns over the increased loss of particles. This, then, raises questions of where in the system would they be lost and how could those losses could be prevented.

And the problems build exponentially when the study moves from the interactions of individual particles to those of bunches of particles. While it may appear as one solid component, a particle accelerator beam is actually formed from individual bunches. For example, Fermilab’s Main injector beam is comprised of up to 588 of them.

To resolve the problems associated with multi-bunch interactions and their innumerable particle constituents, researchers working with ALCF staff on Mira discovered a kind of instability generated by bunch-to-bunch effects that could potentially shut down the whole beam.

These kinds of insights will help in the planning of a high-intensity beam project called the Fermilab Proton Improvement Plan II, which will create neutrino beams for the Long Baseline Neutrino Facility, and help considerably in the next phase of research at CERN’s LHC.

“They’re (CERN) going to be doing high-energy experiments, but intensity matters for them, as well,” notes Amundson. “Their future program involves running at roughly the same energy, but at greater intensity, so they get more statistics and discover more particles.”

This work was supported by the DOE Office of Science (Advanced Scientific Computing Research program) and funded through the Scientific Discovery through Advanced Computing program in the DOE Office of High Energy Physics.

Argonne National Laboratory and Fermilab are supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.