Research on sweat glands suggests a route to better skin grafts

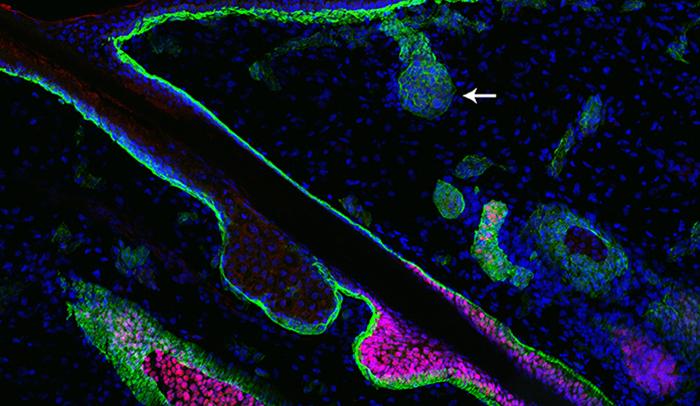

Researchers found that two opposing signaling pathways guide the formation of hair follicles and sweat glands. In humans, hair follicles emerge first (pink), followed by sweat glands (arrowhead). Credit: Laboratory of Mammalian Cell Biology and Development at The Rockefeller University/Science

Now, scientists at Rockefeller University have identified the molecular underpinnings that guide the formation of both hair follicles and sweat glands, finding that two opposing signaling pathways–which can suppress one other–determine what developing skin cells become. Published in Science on December 23, the findings have potential to improve methods for culturing human skin tissue used in grafting procedures. Currently, people undergoing the procedure receive new skin lacking the ability to sweat.

“Sweat glands are vital for regulating temperature and water balance in the body, but we know very little about them,” says Elaine Fuchs, Rebecca C. Lancefield Professor and head of the Robin Chemers Neustein Laboratory of Mammalian Cell Biology and Development. People with damaged sweat glands, which is seen in burn victims and in some genetic disorders, suffer a life-threatening condition–they must remain in temperature-controlled environments and cannot exercise, because it could result in heat stroke and brain damage.

Sweat glands have posed a formidable challenge to researchers because in contrast to humans, where sweat glands and hair follicles coexist, sweat glands in most mammals, including the laboratory mouse, are restricted to tiny regions that are hairless, like the paw. “We took advantage of this regional separation in mice, and compared the gene expression levels in each region to see which signals were active,” says research associate Catherine Lu.

In a developing embryo, small indentations called placodes form in the layer of cells that will become the skin. The fate of these placodes, whether they turn into hair follicles or sweat glands, depends on the molecular signals they receive.

The researchers identified two major signaling pathways, and found that they antagonize, or suppress, one another to specify which fate the placode will become. For a hair follicle to form in mice, a signaling protein called sonic hedgehog (SHH) needs to be present and overpower another signaling protein known as bone morphogenetic protein (BMP). In the sweat gland case, the opposite occurs: BMP is elevated, triggering a cascade of downstream signaling events that results in the silencing of SHH.

Once they understood how the signaling pathways worked in mice, Fuchs and colleagues took one step further to look into human skin.

“At first we were quite puzzled about how this might work in humans, because in mice these signals are regionally separated, allowing one signaling pathway to dominate,” says Lu. “But since these are opposing forces and they cannot happen in the same place at the same time, it wasn't clear how hair follicles and sweat glands develop within the same region in humans.”

By looking at different developmental stages of human embryonic skin, the researchers discovered that in humans, the signals are similar, but separated by time– hair follicles are born first, followed by a burst in BMP that allows sweat glands to emerge.

“This recent evolutionary event that broadened the late embryonic burst of BMP to most skin sites endowed humans with a greater capacity than their hairy cousins to cool their body and therefore live in diverse environments,” explains Fuchs. “The downside is that we have to put on a coat to stay warm!”

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

Superradiant atoms could push the boundaries of how precisely time can be measured

Superradiant atoms can help us measure time more precisely than ever. In a new study, researchers from the University of Copenhagen present a new method for measuring the time interval,…

Ion thermoelectric conversion devices for near room temperature

The electrode sheet of the thermoelectric device consists of ionic hydrogel, which is sandwiched between the electrodes to form, and the Prussian blue on the electrode undergoes a redox reaction…

Zap Energy achieves 37-million-degree temperatures in a compact device

New publication reports record electron temperatures for a small-scale, sheared-flow-stabilized Z-pinch fusion device. In the nine decades since humans first produced fusion reactions, only a few fusion technologies have demonstrated…