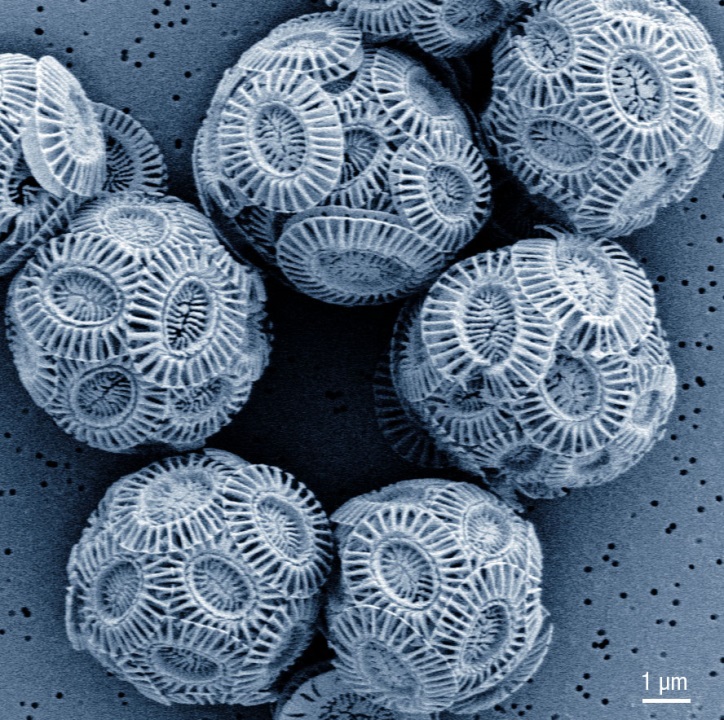

Emiliana huxleyi and other marine algae resides within chalk shells called coccoliths. Fossil coccoliths open a window to the climate in the past while contemporary coccoliths influences our climate.

André Scheffel, MPI-MP

Algae are true all-rounders. In East-Asian countries they are a staple food. But this is not all they have to offer. They are fascinating and highly adaptable organisms, living almost everywhere there is water – in the ocean, in lakes, or even in puddles and in the snow. With ca. 40.000 known species, algae play an essential role in the environment and for humanity.

The marine microalga Emiliania huxleyi is one of the key phytoplankton species and lives in a solid house assembled from chalky platelets which scientists refer to as coccoliths. After death of the algae, the chalky shell sinks to the ocean floor and becomes an abundant component of sea-floor carbonates.

Over millions of years these shells have accumulated to form thick sediment layers, with the chalk cliff of the German island of Rügen being a prominent example. Due to the incorporation of trace elements from the waters surrounding the cells into the chalk structures, which are produced inside the cells, the chemical composition of these sediments can give information about the climate and environment of the past.

Nevertheless, the mechanism of chalk production in calcareous algae (“coccolithophores”) is poorly understood so far. An international research team led by André Scheffel from the MPIMP and Damien Faivre from the MPICI in Potsdam-Golm has now analyzed the processes of chalk production in the dominant marine alga Emiliana huxleyi.

This unicellular alga produces one chalk disk after the other inside the cell and moves them outside upon completion. In this way the outer shell is produced. The production of each chalk scale takes place inside a membrane-bound compartment, called the coccolith vesicle.

Based on microscopic and spectroscopic techniques the team was able to identify an additional, to date undiscovered calcium reservoir, which feeds coccolith formation with calcium and presumably the impurities that have been detected in mature coccolith chalk. Besides calcium this compartment contains other elements, including polyphosphates, which enable accumulation of calcium without its precipitation.

“The discovery of this new component in the calcium metabolism of the alga Emiliania huxleyi gives new opportunities to understand the production of coccoliths and the integration of trace elements”, explains Sanja Sviben, first author of this study. The insights emerging from this study may bring the coccolith composition and seawater chemistry into a mechanistic framework and help in understanding why and how calcification will be affected by changing environmental conditions.

Beside the reconstruction of past environmental conditions, it will be possible to develop predictive models of the future of calcification and the corresponding impact on climate. “Our results can be used to clarify how ocean acidification can influence the chalk production and how this process can adapt to future conditions”, describes André Scheffel.

Being able to predict those future changes is important, due to the impact coccolithophores have on the global carbon cycle. They bind million tons of carbon dioxide yearly, removing the greenhouse gas from the atmosphere. Each chalky coccolith that ends up on the sea-floor removes carbon from the atmosphere-ocean cycle for thousands of years.

The acidification of the oceans due to raising atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations poses a threat to biological chalk formation and the consequences of this on our climate are poorly understood.

Contact

Dr. André Scheffel

Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology

Tel. 0331/567 8358

scheffel@mpimp-golm.mpg.de

Dr. Ulrike Glaubitz

Public Relations

Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology

Tel. 0331/567 8275

glaubitz@mpimp-golm.mpg.de

http://www.mpimp-golm.mpg.de

Katja Schulze

Public Relations

Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces

Tel. 0331/567 9203

katja.schulze@mpikg.mpg.de

http://www.mpikg.mpg.de

Original publication

Sviben, S., Gal., A., Hood., M., A., Bertinetti, L., Politi, Y., Bennet, M., Krishnamoorthy, P., Schertel, A., Wirth, R., Sorrentino, A., Pereiso, E., Faivre, D., Scheffel, A.

A vacuole-like compartment concentrates a disordered calcium phase in a key coccolithophorid alga.

Nature Communications, 14. April 2016, doi: 10.1038/ncomms11228

http://www.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/2064848/pm-kalkalgen