Rerouting of Major Rivers in Asia Provides Clues to Mountains of the Past

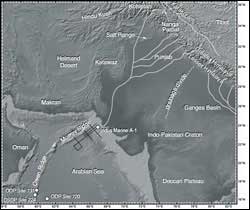

Shaded relief map of the Arabian Sea and surrounding land masses, showing the location of the drill sites and seismic profiles used in the study and major tributaries of the Indus River. (Figure by Peter Clift and Jerzy Blusztajn)

Scientists have long recognized that the collision of the earth’s great crustal plates generates mountain ranges and other features of the Earth’s surface. Yet the link between mountain uplift and river drainage patterns has been uncertain. Now scientists have used laboratory techniques and sediment cores from the ocean to help explain the how rivers have changed course over millions of years.

In a report published in the December 15 issue of Nature, scientists Peter Clift of the University of Aberdeen in the United Kingdom and Jerzy Blusztajn of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution reconstructed the erosional discharge from the Indus River over the past 30 million years and found that the source of those sediments changed five million years ago. Until then, Indus River sediments were produced by erosion of mountains to the north of the collision zone between India and Asia, but five million years ago much more sediment starting coming from the southern Himalayas, part of the deformed Indian plate.

Clift and Blusztajn believe the change is caused by a rerouting of the major rivers of the Punjab region into the Indus River, where they flow into the Arabian Sea west of India. Previously these rivers flowed east and joined the Ganges River before reaching the Bay of Bengal, east of India.

The erosional record in the Arabian Sea is at the center of debates concerning the nature of continent-ocean interactions, and how climate, tectonic activity and erosion are linked. In order to interpret this record, scientists need to understand what sediment is being delivered by the modern Indus River to the coast and transported to the deep sea.

The researchers reconstructed the long-term discharge from the Indus River using both new and previously published data to estimate continental erosion rates. Although some sediment from the rivers stays onshore, about two thirds of the sediment is preserved offshore. Using a series of sediment samples from scientific and industrial drill sites across the Arabian Sea, the researchers reconstructed changing continental erosion rates through time. The technique may enable scientists to eventually date the uplift of the Tibetan Plateau

By studying sediments accumulated in the Arabian Sea, the researchers found strong evidence for a significant change in the Himalayan river systems in the recent geologic past. The sediment in the Arabian Sea forms one of the largest areas of sediment deposition in the oceans and is an important repository of information on the uplift and erosion of the western Himalaya.

“This is the first time such a major sediment capture event has been dated,” said Blusztajn, a researcher in the WHOI Geology and Geophysics Department. “ It has been proposed than such huge events occurred in East Asia, but so far the ages of the capture events there remain unknown. The new isotope stratigraphy provides strong evidence for a major change in the geometry of the western Himalayan river system after five million years ago, probably caused by a change in the mountains.”

Earlier studies by Clift, a visiting scientist at WHOI, and others have shown differences in “isotopic fingerprints” between ancient and modern Indus River sediments.

The new findings suggest the ancient Punjabi rivers were connected to the Ganges and not the Indus River, and that the rivers were diverted or rerouted from their original southeasterly flow by the uplift of mountain ranges in modern day Pakistan. The majority of material contributing to the Indus River now is coming from four large rivers in the Punjab: the Sutlej, Ravi, Chennab and Jellum rivers, forming the “bread basket” of northern India and Pakistan.

“This study highlights the need to account for sediment capture events like this in interpreting erosion records from the marine environment,” Blusztajn said. “Studying modern river sediments and comparing them with marine sediment allows the volume and composition of inputs from different sources to be quantified. If the marine sedimentation process can be related to the modern mountains and drainage system, we may be able to use ancient sediments to reconstruct what the mountains looked like in the geologic past.”

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.whio.eduAll latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Skyrmions move at record speeds

… a step towards the computing of the future. An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be…

A flexible and efficient DC power converter for sustainable-energy microgrids

A new DC-DC power converter is superior to previous designs and paves the way for more efficient, reliable and sustainable energy storage and conversion solutions. The Kobe University development can…

Technical Trials for Easing the (Cosmological) Tension

A new study sorts through models attempting to solve one of the major challenges of contemporary cosmic science, the measurement of its expansion. Thanks to the dizzying growth of cosmic…