The secret weapons of cabbages: Overcome by butterfly coevolution

Larva of the Black Jezebel butterfly (Delias nigrina) feeding on mistletoes. This species has lost the ability to feed on cabbage plants. Heiko Vogel / Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology

This study appears 50 years after a classic paper by Drs. Paul Ehrlich and Peter Raven that formally introduced the concept of coevolution using butterflies and plants as primary examples. The present study not only provides striking support for coevolution, but also provides fundamentally new insights into its genetic basis in both groups of organisms. (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, June 2015).

The major chemical defense of cabbage plants and relatives belonging to the mustard family Brassicales is based on a two-component activated system composed of non-toxic precursors (the glucosinolates or mustard oils) and plant enzymes (myrosinases). These are spatially separated in healthy tissue, but when the tissue is damaged by chewing insects both components are mixed and the so-called “mustard oil bomb” is ignited, producing a series of toxic breakdown products.

It is exactly these breakdown products that can be appealing to humans in certain concentrations (as found in mustard) as well as deterrent or toxic to unadapted herbivores. However, some insects have specialized on cabbage plants and have found various ways to cope with their host plant defenses. Among these are pierids (the White butterflies) and relatives, which specialized on these new host plants shortly after the evolutionary appearance of the Brassicales and their “invention” of the glucosinolate-based chemical defense.

Comparing the evolutionary histories of these plants and butterflies side-by-side, the researchers discovered that major advances in the chemical defenses of the plants were followed by butterflies evolving counter-tactics that allowed them to keep eating these plants. This back-and-forth dynamic was repeated over nearly 80 million years, resulting in the formation of more new species, compared to other groups of plants without glucosinolates and their herbivores.

Thus, the successful adaptation to glucosinolates enabled this butterfly family to rapidly diversify; and pierids are nowadays widespread with some species being very abundant worldwide, such as the Small White and the Large White. While most butterflies of this family now feed on Brassicales, some relatives stick with the ancestral preference for legumes and cannot detoxify glucosinolates. Secondary host shifts away from Brassicales have also taken place, with some species now feeding on other host plants such as mistletoes.

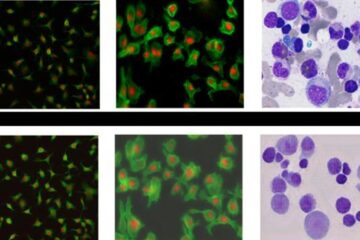

By sequencing the genomes of both plants and butterflies, the researchers discovered the genetic basis for this arms race. Advances on both sides were driven by the appearance of new copies of genes, rather than by simple point mutations in the plants’ and butterflies’ DNA.

Furthermore butterfly species that first developed gene copies adapted to glucosinolates, but later shifted to feeding on non-Brassicales plants such as mistletoes, showed a different pattern. The genes responsible for the ‘mustard-adaptations’ have completely vanished from their genomes. Even an adaptation that took 80 million years to evolve can be discarded when it is no longer needed.

The research is the product of an international team of plant scientists from the University of Missouri, USA and butterfly biologists from Stockholm University, Sweden and the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Germany.

Original Publication:

Edger, P.P., Heidel-Fischer, H. M., Bekaert, M., Rota, J., Glöckner, G., Platts, A. E., Heckel, D. G., Der, J. P., Wafula, E. K., Tang, M., Hofberger, J. A., Smithson, A., Hall, J. C., Blanchette, M., Bureau, T. E., Wright, S. I., dePamphilis, C. W., Schranz, M. E., Barker, M. S., Conant, G. C., Wahlberg, N., Vogel, H., Pires, J. C., Wheat, C. W. (2015). The butterfly plant arms-race escalated by gene and genome duplications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA.

DOI 10.1073/pnas.1503926112

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1503926112

Further Information:

Dr. Hanna Heidel-Fischer, Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Hans-Knöll-Straße 8, 07745 Jena, Germany, Tel. +49 3641 57-1516, E-Mail hfischer@ice.mpg.de

Dr. Heiko Vogel, Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Hans-Knöll-Straße 8, 07745 Jena, Germany, Tel. +49 3641 57-1512, E-Mail hvogel@ice.mpg.de

Contact and Picture Requests:

Angela Overmeyer M.A., Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Hans-Knöll-Str. 8, 07743 Jena, Germany, +49 3641 57-2110, E-Mail overmeyer@ice.mpg.de

Download of high resolution images via http://www.ice.mpg.de/ext/downloads2015.html

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Agricultural and Forestry Science

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…