New finding could pave way to faster, smaller electronics

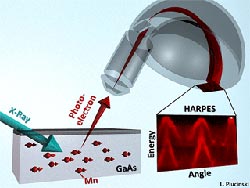

The new hard X-ray angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy technique lets UC Davis researchers look inside new materials and study their properties. (Lukasz Plucinski, Peter Grunberg Institute/graphic) <br>

Materials of this type might be used to read and write digital information not by using the electron’s charge, as is the case with today’s electronic devices, but by using its “spin.”

Understanding the magnetic behavior of atoms is key to designing spintronics materials that could operate at room temperature, an essential property for applications.

The new study used a novel technique, hard X-ray angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy or HARPES, developed by Charles Fadley, distinguished professor of physics at UC Davis and the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, and recent UC Davis doctoral graduate Alexander Gray, together with colleagues at LBNL and in Germany and Japan.

The research represents the first major application of the HARPES technique, which was first described in a proof-of-principle paper by Gray, Fadley and colleagues last year.

The latest work was published Oct. 14 in the journal Nature Materials.

Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy uses Einstein's famous photoelectric effect to study materials. If you bombard atoms with light particles — photons — you knock out electrons, known as photoelectrons, which fly out at precise angles, energies and spins depending on the structure of the material.

For many years researchers have used “soft” or low-energy X-rays as the photon source, but the technique can look only at the top nanometer of a material — about five atoms deep. Fadley and Gray developed a method that uses “hard,” high-energy X-rays to look much deeper inside a material, to a depth of about 40 to 50 atoms.

The researchers selected gallium manganese arsenide because of its potential in technology. Gallium arsenide is a widely used semiconductor. Add a few percent of manganese atoms to the mix, and in the right conditions — a temperature below 170 Kelvin (about 150 degrees below zero Fahrenheit), for one — it becomes ferromagnetic like iron, with all of the individual manganese atomic magnets lined up in the same direction. Physicists call this class of materials dilute magnetic semiconductors.

There were two competing ideas to explain how gallium manganese arsenide becomes magnetic at certain temperatures. The HARPES study shows that, in fact, both mechanisms contribute to the magnetic properties.

“We now have a better fundamental understanding of electronic interactions in dilute magnetic semiconductors that can suggest future materials,” Fadley said. “HARPES should provide an important tool for characterizing these and many other materials in the future.”

Gray and Fadley conducted the study at the SPring-8 synchrotron radiation facility, operated by the Japanese National Institute for Materials Sciences. New HARPES studies are now under way at LBNL's Advanced Light Source synchrotron.

Other authors on the paper are Jan Minár, Juergen Braun and Hubert Ebert, Ludwig Maximillian University, Munich, Germany; Shigenori Ueda, Yoshiyuki Yamashita and Keisuke Kobayashi, National Institute for Materials Science, Hyogo, Japan; Oscar Dubon and Peter Stone, LBNL and UC Berkeley; Jun Fujii and Giancarlo Panaccione, Istituto Officina dei Materiali, Trieste, Italy; Lukasz Plucinski and Claus Schneider, Peter Grünberg Institute, Jülich, Germany. Gray is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences, Stanford University, and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park, Calif.

The work was supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Energy and the governments of Japan and Germany.

About UC Davis

For more than 100 years, UC Davis has engaged in teaching, research and public service that matter to California and transform the world. Located close to the state capital, UC Davis has more than 32,000 students, more than 2,500 faculty and more than 21,000 staff, an annual research budget that exceeds $684 million, a comprehensive health system and 13 specialized research centers. The university offers interdisciplinary graduate study and more than 100 undergraduate majors in four colleges — Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Biological Sciences, Engineering, and Letters and Science. It also houses six professional schools — Education, Law, Management, Medicine, Veterinary Medicine and the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing.

Media contact(s):

Charles Fadley, Physics, (530)752-8788, csfadley@ucdavis.edu

Andy Fell, UC Davis News Service, (530) 752-4533, ahfell@ucdavis.edu

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.ucdavis.eduAll latest news from the category: Materials Sciences

Materials management deals with the research, development, manufacturing and processing of raw and industrial materials. Key aspects here are biological and medical issues, which play an increasingly important role in this field.

innovations-report offers in-depth articles related to the development and application of materials and the structure and properties of new materials.

Newest articles

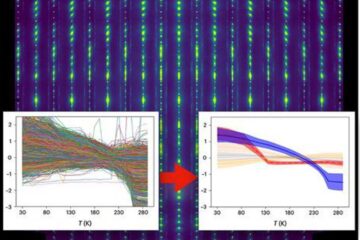

Machine learning algorithm reveals long-theorized glass phase in crystal

Scientists have found evidence of an elusive, glassy phase of matter that emerges when a crystal’s perfect internal pattern is disrupted. X-ray technology and machine learning converge to shed light…

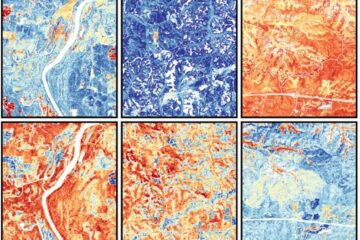

Mapping plant functional diversity from space

HKU ecologists revolutionize ecosystem monitoring with novel field-satellite integration. An international team of researchers, led by Professor Jin WU from the School of Biological Sciences at The University of Hong…

Inverters with constant full load capability

…enable an increase in the performance of electric drives. Overheating components significantly limit the performance of drivetrains in electric vehicles. Inverters in particular are subject to a high thermal load,…