Tentacles of venom: new study reveals all octopuses are venomous.

The work indicates that they all share a common, ancient venomous ancestor and highlights new avenues for drug discovery.

Conducted by scientists from the University of Melbourne, University of Brussels and Museum Victoria, the study was published in the Journal of Molecular Evolution.

Dr Bryan Fry from the Department of Biochemistry at the Bio21 Institute, University of Melbourne said that while the blue-ringed octopus species remain the only group that aredangerous to humans, the other species have been quietly using their venom for predation, such as paralysing a clam into opening its shell.

“Venoms are toxic proteins with specialised functions such as paralysing the nervous system” he said.

“We hope that by understanding the structure and mode of action of venom proteins we can benefit drug design for a range of conditions such as pain management, allergies and cancer.”

While many creatures have been examined as a basis for drug development, cephalopods (octopuses, cuttlefish and squid) remain an untapped resource and their venom may represent a unique class of compounds.

Dr Fry obtained tissue samples from cephalopods ranging from Hong Kong, the Coral Sea, the Great Barrier Reef and Antarctica. The team then analysed the genes for venom production from the different species and found that a venomous ancestor produced one set of venom proteins, but over time additional proteins were added to the chemical arsenal.

The origin of these genes also sheds light on the fundamentals of evolution, presenting a prime example of convergent evolution where species independently develop similar traits. The team will now work on understanding why very different types of venomous animals seem to consistently settle on the similar venom protein composition, and which physical or chemical properties make them predisposed to be useful as toxin.

“Not only will this allow us to understand how these animals have assembled their arsenals, but it will also allow us to better exploit them in the development of new drugs from venoms,” said Dr Fry.

“It does not seem a coincidence that some of the same protein types have been recruited for use as toxins across the animal kingdom.”

For more information:

Dr Bryan Fry

Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

Bio21 Institute, University of Melbourne

Email: bgf@unimelb.edu.au

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.unimelb.edu.auAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

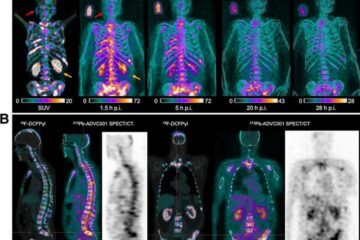

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…