Chicken genome gives insights into human genome

The draft sequence of the wild chicken, Gallus gallus, will be published in the Dec 9th issue of Nature (cover story). The analysis of this genome is not about getting bigger eggs and tastier chicken – it’s giving scientists surprising insights into the human genome. Researchers can use these new data as a tool to identify similar sequences in humans – regions previously thought to be ‘junk’ DNA in the human. These sequences must have an important role if they have been conserved over the 310 million years since the two lineages diverged.

Ewan Birney of the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI), whose Ensembl team performed much of the computational analysis of the genome, explains the importance of the chicken: “We needed to study a genome that is at the right evolutionary distance from humans. Until now, all the fully sequenced genomes have been too closely related or too distant to get the information that we wanted. For example, the mouse genome gave us lots of useful information about coding regions but we were surprised at how much of the junk DNA was almost identical in mouse and human. This is because not enough time has passed since humans and mice diverged from their common ancestor. As a result, we gained very little new insight into the non-coding regions of the human genome.”

The chicken genome, on the other hand, turns out to be an invaluable tool for studying the human genome. It is at the ideal evolutionary distance from the human. During the 310 million years since their paths diverged, sequences with important functions, which include genes and their regulatory motifs, have been under pressure not to mutate because changes to the sequence would have detrimental consequences. By contrast, areas of the genome with no function – bona fide ‘junk’ DNA – have been under no such pressure, and sufficient time has lapsed for these regions to become quite distinct in the two genomes.

“We found strong conservation in regions of humans that were previously thought to be junk DNA. They don’t code for RNA or for protein and their function is still a complete mystery, but they must have been conserved for an important reason,” Birney says. “Without the chicken genome, we would have continued to wrongly believe that these regions in humans were unimportant.”

Scientists have also used the new genome to find a set of genes that is notoriously hard to pin down. These ‘non-coding RNA (ncRNA) genes’ code for functional RNA molecules rather than proteins. Protein-coding genes are relatively easy to identify because their sequences contain characteristic signals that say ‘start here’ and ‘stop here’. Unfortunately ncRNA genes are less straightforward to pick out. This problem is confounded in humans because we have a lot of ‘pseudogenes’, sequences that evolved from functional genes that were copied and then fell into disrepair. Chickens, however, contain very few pseudo-genes so their set of ncRNA genes is likely to be a functional set whose counterparts can now be identified in humans. It’s also been easier to find the control switches within protein-coding genes. “When you align the chicken and human sequences, the conserved regions really leap out at you. This doesn’t happen when you do the same with the mouse and human because the unimportant bits of sequence in between didn’t have time to diverge,” explains Birney.

Most of the functional differences and commonalities between chickens and humans can be revealed by studying their protein-coding genes. Peer Bork’s team at EMBL-Heidelberg, together with Chris Ponting’s team at The Medical Research Council Functional Genetics Unit based at Oxford University, approached this task by looking first for shared genes and then for shared sequences that define gene families.

“We are more similar to birds than you would think,” explains Bork. “About 60% of the chicken protein-coding genes have human equivalents. But when you look at the entire gene families they have many more families in common: for example, mammals have expanded a certain family of keratins for hair production, whereas birds use a different set for the formation of feathers and claws. We also found some chicken genes involved in immune function that previously were believed to be unique to humans.”

An international consortium of over 170 people from 49 different institutes across the globe assembled and analysed this genome. All of the data has been deposited into freely available public databases (see notes).

“Having the chicken genome sequence is like being armed with an antiques guide at a flea market: suddenly you have a tool that allows you to recognize which pieces are valuable,” concludes Birney. We’re all sure to reap the rewards.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.embl.deAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

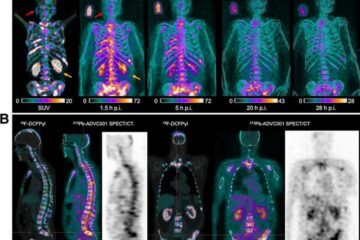

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…