Microbe may explain evolutionary origins of DNA folding

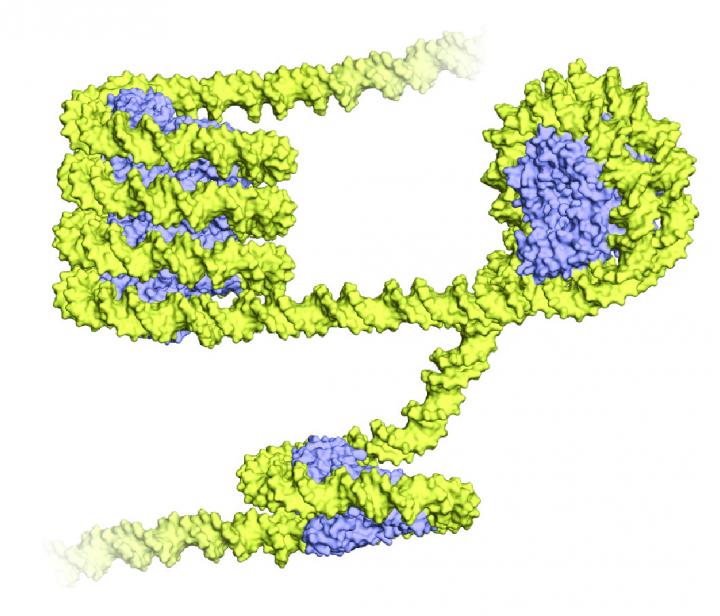

Archaea wrap their DNA (yellow) around proteins called histones (blue), shown above in a 3-D representation. The wrapped structure bears an uncanny resemblance to the eukaryotic nucleosome, a bundle of eight histone proteins with DNA spooled around it. But unlike eukaryotes, archaea wind their DNA around just one histone protein, and form a long, twisting structure called a superhelix. Credit: Francesca Mattiroli

“If you look at the nitty gritty, it's identical,” said Karolin Luger, a professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Colorado Boulder and an HHMI Investigator. “It just blows my mind.”

The archaeal DNA folding, described today in the journal Science, hints at the evolutionary origins of genome folding, a process that involves bending DNA and one that is remarkably conserved across all eukaryotes (organisms that have a defined nucleus surrounded by a membrane).

Like Eukarya and Bacteria, Arachaea represent one of the three domains of life. But Archaea are thought to include the closest living relatives to an ancient ancestor that first hit on the idea of folding DNA.

Scientists have long known that cells in all eukaryotes, from fish to trees to people, pack DNA in exactly the same way. DNA strands are wound around a 'hockey puck' composed of eight histone proteins, forming what's called a nucleosome. Nucleosomes are strung together on a strand of DNA, forming a “beads on a string” structure. The universal conservation of this genetic necklace raises the question of its origin.

If all eukaryotes have the same DNA bending style, “then it must have evolved in a common ancestor,” said study co-author John Reeve, a microbiologist at Ohio State University. “But what that ancestor was, is a question no one asked.”

Earlier work by Reeve had turned up histone proteins in archaeal cells. But, archaea are prokaryotes (microgorganisms without a defined nucleus), so it wasn't clear just what those histone proteins were doing. By examining the detailed structure of a crystal that contained DNA bound to archaeal histones, the new study reveals exactly how DNA packing works.

Luger and her colleagues wanted to make crystals of the histone-DNA complex in Methanothermus fervidus, a heat-loving archaeal species. Then, they wanted to bombard the crystals with X-rays. This technique, called X-ray crystallography, yields precise information about the position of each and every amino acid and nucleotide in the molecules being studied. But growing the crystals was tricky (the histones would stick to any given stretch of DNA, making it hard to create consistent histone-DNA structures), and making sense of the data they could get was no easy feat.

“It was a very gnarly crystallographic problem,” said Luger.

Yet Luger and her colleagues persisted. The researchers revealed that despite using a single type of histone (and not four as do eukaryotes), the archaea were folding DNA in a very familiar way, creating the same sort of bends as those found in eukaryotic nucleosomes.

But there were differences, too. Instead of individual beads on a string, the archaeal DNA formed a long superhelix, a single, large curve of already twisty DNA strands.

“In Archaea, you have one single building block,” Luger said. “There is nothing to stop it. It's almost like it's a continuous nucleosome, really.”

This superhelix formation, it turns out, is important. When CU Boulder postdoctoral researcher Francesca Mattiroli, together with Thomas Santangelo's lab at Colorado State University, created mutations that interfered with this structure, the cells had trouble growing under stressful conditions. What's more, the cells seemed to not be using a set of their genes properly.

“It's clear with these mutations that they can't form these stretches,” Mattiroli said.

The results suggest that the archaeal DNA folding is an early prototype of the eukaryotic nucleosome.

“I don't think there's any doubt that it's ancestral,” Reeve said.

Still, many questions remain. Luger says she'd like to look for the missing link — a nucleosome-like structure that bridges the gap between the simple archaeal fold and the elaborate nucleosome found in eukaryotes, which can pack a huge amount of DNA into a small space and regulate gene behavior in many ways.

“How did we get from here to there?” she asks.

###

*This release was written by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and is re-used with permission.*

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Properties of new materials for microchips

… can now be measured well. Reseachers of Delft University of Technology demonstrated measuring performance properties of ultrathin silicon membranes. Making ever smaller and more powerful chips requires new ultrathin…

Floating solar’s potential

… to support sustainable development by addressing climate, water, and energy goals holistically. A new study published this week in Nature Energy raises the potential for floating solar photovoltaics (FPV)…

Skyrmions move at record speeds

… a step towards the computing of the future. An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be…