Giving Ancient Life Another Chance to Evolve

Using a process called paleo-experimental evolution, Georgia Tech researchers have resurrected a 500-million-year-old gene from bacteria and inserted it into modern-day Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria. This bacterium has now been growing for more than 1,000 generations, giving the scientists a front row seat to observe evolution in action.

“This is as close as we can get to rewinding and replaying the molecular tape of life,” said scientist Betül Kaçar, a NASA astrobiology postdoctoral fellow in Georgia Tech’s NASA Center for Ribosomal Origins and Evolution. “The ability to observe an ancient gene in a modern organism as it evolves within a modern cell allows us to see whether the evolutionary trajectory once taken will repeat itself or whether a life will adapt following a different path.”

In 2008, Kaçar’s postdoctoral advisor, Associate Professor of Biology Eric Gaucher, successfully determined the ancient genetic sequence of Elongation Factor-Tu (EF-Tu), an essential protein in E. coli. EFs are one of the most abundant proteins in bacteria, found in all known cellular life and required for bacteria to survive. That vital role made it a perfect protein for the scientists to answer questions about evolution.

After achieving the difficult task of placing the ancient gene in the correct chromosomal order and position in place of the modern gene within E. coli, Kaçar produced eight identical bacterial strains and allowed “ancient life” to re-evolve. This chimeric bacteria composed of both modern and ancient genes survived, but grew about two times slower than its counterpart composed of only modern genes.

“The altered organism wasn’t as healthy or fit as its modern-day version, at least initially,” said Gaucher, “and this created a perfect scenario that would allow the altered organism to adapt and become more fit as it accumulated mutations with each passing day.”

The growth rate eventually increased and, after the first 500 generations, the scientists sequenced the genomes of all eight lineages to determine how the bacteria adapted. Not only did the fitness levels increase to nearly modern-day levels, but also some of the altered lineages actually became healthier than their modern counterpart.

When the researchers looked closer, they noticed that every EF-Tu gene did not accumulate mutations. Instead, the modern proteins that interact with the ancient EF-Tu inside of the bacteria had mutated and these mutations were responsible for the rapid adaptation that increased the bacteria’s fitness. In short, the ancient gene has not yet mutated to become more similar to its modern form, but rather, the bacteria found a new evolutionary trajectory to adapt.

The results were presented at the recent NASA International Astrobiology Science Conference. The scientists will continue to study new generations, waiting to see if the protein will follow its historical path or whether it will adopt via a novel path altogether.

“We think that this process will allow us to address several longstanding questions in evolutionary and molecular biology,” said Kaçar. “Among them, we want to know if an organism’s history limits its future and if evolution always leads to a single, defined point or whether evolution has multiple solutions to a given problem.”

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.gatech.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

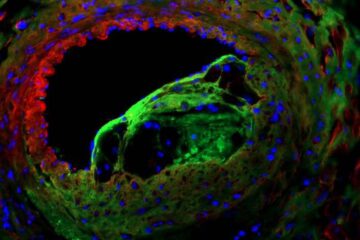

Solving the riddle of the sphingolipids in coronary artery disease

Weill Cornell Medicine investigators have uncovered a way to unleash in blood vessels the protective effects of a type of fat-related molecule known as a sphingolipid, suggesting a promising new…

Rocks with the oldest evidence yet of Earth’s magnetic field

The 3.7 billion-year-old rocks may extend the magnetic field’s age by 200 million years. Geologists at MIT and Oxford University have uncovered ancient rocks in Greenland that bear the oldest…

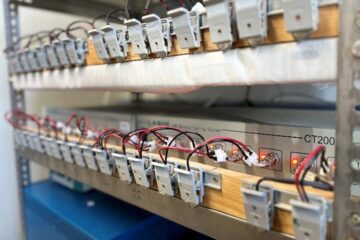

Decisive breakthrough for battery production

Storing and utilising energy with innovative sulphur-based cathodes. HU research team develops foundations for sustainable battery technology Electric vehicles and portable electronic devices such as laptops and mobile phones are…